It Follows, part 1: Evil threatens Suburbia

The freeze frames from It Follows used in this article are taken from a screener made available to Montages by the film’s Norwegian distributor. The article contains merely mild spoilers, up to a certain point clearly marked in the text, after which central plot points are revealed.

*

It Follows is a diabolical evocation of a hypnotic state of nightmare, where the viewer becomes a paralysed witness to destruction. The film is also an engaging portrait of a teenage girl and her environment.

Director David Robert Mitchell‘s second feature film inspires awe far outside the ranks of horror film aficionados. One reason is its openness to interpretation from a plethora of angles. In this first entry in a series of three articles, we shall look at 10 possible ways into the film, and try to put into words and pictures what makes the film so special. The second article explores central motifs like sleep, water and red colour coding. The third article revolves around the film’s staging and aesthetics.

1. The basic elements of life

Like much great art, It Follows operates on basic elements of human life. Family, sex, life, death, food, water and sleep are evoked both above and beneath the work’s surface. The curse of the story is transmitted to the next person in the line through sexual intercourse. What is supposed to lead to life leads to death, after paranoid, prolonged torment where the victim’s last hours are going to be as horrific as possible. The imperturbable, deadly “Follower” often appears in the body of someone close to you, in order to inflict maximum emotional torture before killing you.

It Follows contrasts this with life-supporting elements like food, water and sleep. (Red, the most striking of the primary colours, is another important motif in the film.) The enigmatic plate of food in the above image appears in two situations, but always remains untouched. Fetishised through an unusual camera gaze, both plates become almost nauseating. Water appears in many variations: drinking (in large quantities), rain, swimming pools, beaches. One of the most repulsive Follower appearances comes as a battered women in a state of eternal urination.

Near the end, a character reads aloud literary words of wisdom about the inevitability of death and the end of consciousness, while she nevertheless, almost on autopilot, is munching away on a sandwich. Her monotonous voice and the lethargic atmosphere suggest that the ramifications of the words are not entirely digested, and one of the listeners has dozed off, among the film’s innumerable occurrences of sleep.

2. Maika Monroe

The lead character is played by the enchanting Maika Monroe. She has both an inner beauty and one of those faces one never tires of. Mitchell is constantly revealing new aspects of her appearance, as if she is several different persons through the film. Even though not required to display the same range, she has some of the same magnetism and plasticity as Ine Marie Wilmann in the recent Norwegian film Homesick.

At the same time Monroe is utterly believable as a perfectly normal American youth, and with her likeable personality she has marvellous abilities as an identification object – one reason that It Follows has such power to convince.

Already here It Follows starts to stand out from usual horror fare: we become interested in the main character through the depth of acting and personality. For example, Barbara Hershey adds an extra dimension of character drama to The Entity (Sidney J. Furie, 1982), while the undeniably likeable and attractive Jocelin Donahue never manages to lift The House of the Devil (Ti West, 2009) up to something more than a brilliant horror film.

Monroe’s sensitivity also gives It Follows a poetic touch: Her character is connected to grass, bushes and trees, and I have never seen a horror film with so many peaceful glances towards the heavens and crowns of trees – something that becomes one of the film’s many motifs.

3. Teen film

It Follows is almost as much a teen film than a horror movie. It continues David Robert Mitchell‘s singular approach to this genre in his debut work The Myth of the American Sleepover (2010). There we follow no less than 17 important characters during the last weekend before a new school year. A large number of parties are organised where sleeping over is part of the programme, and the characters almost seem like nomads on eternal wanderings, searching for love, understanding and identity. Also Mitchell’s debut film is fresh and original in its genre, with its painstakingly realistic characterisations and sober tone.

It Follows is almost as much a teen film than a horror movie. It continues David Robert Mitchell‘s singular approach to this genre in his debut work The Myth of the American Sleepover (2010). There we follow no less than 17 important characters during the last weekend before a new school year. A large number of parties are organised where sleeping over is part of the programme, and the characters almost seem like nomads on eternal wanderings, searching for love, understanding and identity. Also Mitchell’s debut film is fresh and original in its genre, with its painstakingly realistic characterisations and sober tone.

Exactly like in It Follows – except for the latter’s most acute horror situations – no one is raising their voice. The dialogue is marked by small pauses. Both works have a hypnotic feel and superb casting. Mitchell manages to paint a portrait of ordinary teenagers, but also make us feel that each of them is unique, with emotional depth. Also It Follows dwells in several situations on the fact that groups of teenagers sleep over at others’ houses.

In It Follows Monroe plays 19-year-old Jay. She is surrounded by a regular coterie: her little sister Kelly (Lili Sepe), their common friend, the lightly eccentric Yara (Olivia Luccardi), and Kelly’s workmate, the mild-mannered Paul (Keir Gilchrist). Infatuated with Jay, Paul keeps hanging around waiting for his chance, in the process having to endure a lot of contempt and humiliation from the girls. The handsome, somewhat Johnny Depp-like Greg (Daniel Zovatto) lives across the street, and becomes engaged in Jay’s predicament, from compassion but perhaps most of all because he wants to sleep with her. Another central character is Jeff (Jake Weary), who under a false name has become Jay’s boyfriend at the start of the film. Jeff too would like to sleep with Jay, but his motivation is very different: to pass the curse on to her so he can get rid of the Follower chasing him. (If Jay gets killed herself, however, the curse returns to the previous link in the chain, so in practice Jeff is only buying himself some time.)

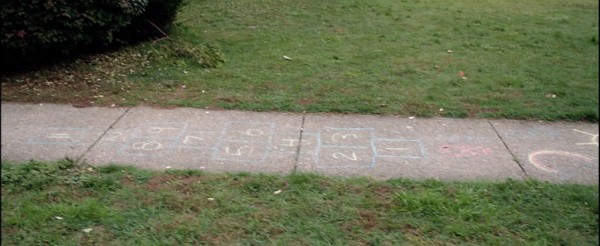

Swimming pools are important arenas to Mitchell. The Myth of the American Sleepover opens at a pool, another one is central during one of the biggest parties, and a swimming hall is the location for a very important scene, where one of the boys is quietly courting two twin girls, whom he both has feelings for. (This is given a soft echo in It Follows, where in the scene where the mood is closest to the debut film, it is revealed that Paul has kissed both Jay and her sister.) Jay is introduced in a temporary swimming pool in the backyard – a construct that shall become a recurring feature – and the film’s climax unfolds in a swimming hall. As Britt Sørensen is pointing out in her review (behind a paywall) in the Norwegian newspaper Bergens Tidende, the film also has things in common – the work’s tone, as well as important locations like a playground and a swimming pool (here as well, the location of the climax) – with Tomas Alfredson‘s Let the Right One in (2008).

Incidentally, the finale in the swimming hall, where the teens have laid a plan to obliterate the Follower once and for all, has been mentioned as a weakness with It Follows. This author too was wondering a bit at the first encounter with the film, but this sequence has grown into a definitive highlight. It may feel unmusical that this action-oriented, highly dramatic set piece breaks with the rest of the work’s sobriety, but it is virtuosic both in its mise-en-scène and purely cinematographic look. Surreal underwater shots, an otherwordly play of light reflected in walls and ceiling, delicate purple colour tones, atmospheric and stylised camera movements, the bizarre sight of household appliances submerged in water – and the sequence also works as drama, if anyone is wondering! Something that may have caused problems for some is Mitchell’s very daring approach to the build-up: he slows the film’s pace to almost zero, devoting more than three and a half minutes for preparation and waiting for the Follower to eventually turn up.

4. The Carpenter Connection

John Carpenter‘s horror movies are pointed out as references and sources of inspiration for It Follows. In connection with this piece I have just seen Halloween (1978) and The Fog (1980). I am aware of being on thin ice – being no expert on horror films and my knowledge of the two films is only superficial – but it looks like David Robert Mitchell is operating in a totally different register.

Carpenter appears as a capable and inventive craftsman, but Mitchell is a visionary artist with a much higher ambition and a broader range, both thematically and emotionally. It Follows combines Dostoyevsky and a poem by T. S. Eliot with old, corny science fiction movies, something that can be said to be emblematic for how Mitchell is making great art in a genre associated with “low culture”. The mood is also different: where Carpenter is thrilling and seductive, Mitchell is oppressive.

While It Follows seems to follow a carefully worked out, overall plan for the imagery, Carpenter is more governed by whim and impulse. It is typical how long he lingers on the steep staircase down to the lighthouse in The Fog. Visually it looks great, but with this kind of emphasis one expects these stairs to play a role later in the film (for example, preventing the character’s escape). But no, it’s just a cool idea there and then. Furthermore, Carpenter devotes a lot of space to the characters, but despite the amount of striving they remain superficial, but in Mitchell they are interesting in themselves, with characterisations emerging organically from the material. Lastly, the Jamie Lee Curtis of Halloween falls rather flat compared to Maika Monroe, both in personality and ability of acting scared in a natural way.

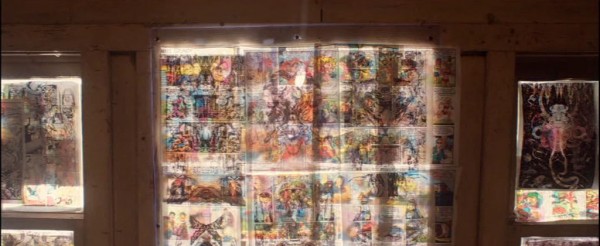

Nevertheless, Mitchell seems enamored with his predecessor, because there are a plethora of references from It Follows to Halloween: doors are very important (as well as in The Fog); a run-down house is ransacked in the search for a criminal who has lived there (including a nifty “scare moment”: respectively, a gutter and a wall come crashing down); horrific things happen in houses across from each other; old science fiction movies play on TV; the comic books with fictitious names in Halloween are answered by the porno magazines with equally fictitious titles.

Disasterpeace (Richard Vreeland) has been celebrated for the synth soundtrack for It Follows and it plays an immeasurable role in the film’s appeal: alternately piercingly dissonant, synthetically romantic, churningly monotonous. A lyrical high point occurs when the teens are approaching the swimming hall, where dreamy images, magic-hour light, and an undulating handheld camera are combined with a grating, siren-like hymn laid over a motor-like, ticking theme.

The soundtrack is clearly inspired by Carpenter’s self-composed music for his films, but also here the predecessor ends up with the shortest straw. While the (undeniably great) music in Carpenter has as its main purpose to be thrilling and tension-building, It Follows again operates in a much broader register, since in addition to sharing those qualities, it comments upon, makes strange, and at times stands in opposition to, the images. It is not without humorous incident either, with “mini-flourishes” à la Ennio Morricone. The music is also more varied and contains a larger number of themes. Speaking of sound, we should not forget that Mitchell also exploits absolute silence in exhilarating fashion in many scenes.

5. Relentlessness in pacing and form

Except for the showdown in the swimming hall where Mitchell lets his hair down, much of the film’s sustained intensity springs from a systematic approach to form. He decides on a limited palette of devices from which he is reluctant to depart, applying them in methodical variations.

One of the most hypnotic and intensifying devices in film language is letting the camera close in on situations and characters, and It Follows has an enormous high rate of shots where the camera is inexorably sneaking closer. It becomes almost comical when one realises how much many scenes rest on this “trick”, which is laughably simple, but the effect is indisputable and mesmerising. (An extra dimension is added in a film where a supernatural killing machine is constantly threatening to close in on the characters.)

One of the most visually seductive examples is the early scene where Jay is making love to Jeff:

The movement is clearly marked and is here meant to have a consciously lyrical effect on the viewer. The great thing above this device, however, is that at a slow pace it most often goes completely “under the radar”, having a merely unconscious effect. Unable to figure out why, the viewer just has a feeling of being relentlessly pulled forward, enshrouded in a mood of smouldering, ever-intensifying tension or quest for understanding. This scene is a good example:

All the driving in the film becomes part of its relentless forward motion:

It Follows is in fact more reminiscent of Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) than Carpenter’s films, with common features like a formal iron grip, hypnotic effect, genre-transcending ambition, oppressive mood and all-encompassing paranoia. Mitchell’s penchant for filming the characters in rhythmic alternation from behind and facing the camera is incidentally a well-known Kubrick trope, applied in most extensive fashion in precisely The Shining.

Our thoughts also go to M. Night Shyamalan‘s halcyon days. The methodical approach to storytelling style and visuality, slow pacing used to increase tension, art film devices in a genre film – all this is reminiscent of works like Unbreakable (2000) and Signs (2002). Furthermore, the importance of the colour red (which is also prominent in Halloween) and some of the Followers’ battered states remind one of the ghosts in Shyamalan’s breakthrough film The Sixth Sense (1999). Mitchell’s scene where Jay discovers a Follower in the kitchen seems a direct reference to the situation in The Sixth Sense where the boy encounters a ghost in his own kitchen. And with both of his films taking place in (the suburbs of) Detroit, by a director who grew up in the area, Mitchell could possibly become to Detroit what Shyamalan was to Philadelphia?

Mitchell and Shyamalan often stage horror set pieces in a sober, almost everyday fashion. At their best, they prove an ability to tap into mankind’s collective unconscious, dredging up our fears in their most fundamental form, so that the scenes remain deeply unsettling regardless of how many times they are watched. It Follows and The Sixth Sense also share a strategy of alternating between self-consciously virtuosic scenes, often filmed in one take, and scenes constructed by film language’s most fundamental building blocks.

In the opening scene of It Follows the camera is placed in the middle of the street and then performs a painstaking pirouette where it follows a terrified girl running away from an invisible enemy. (The take lasts 106 seconds.) The contrast between the almost overly controlled camera and the girl’s apparently irrational state contributes to the scene’s unhinged mood. Later, the camera makes a similar movement (for 91 seconds) where for each iteration of the circle it captures a Follower coming increasingly closer. The circle strategy also appears in less grandiose versions and constitutes one of the film’s many motifs.

This type of scene is so memorable that one leaves the cinema with an impression that It Follows is almost experimental in its form. But one of many reasons for the film’s emotionally mesmerising effect is the fact that many situations actually rest on some of cinema’s most fundamental methods for creating identification and immersion. Scenes like Jay sitting in a playground afraid that a Follower might turn up, or Jay looking out of her bedroom window and finally discovering a Follower in the street, act like clockwork, in a continuous, fluid alternation between close-ups of Jay and shots of what she is seeing, in classic suspense manner à la Hitchcock. For It Follows as a whole, we therefore end up with an average shot length as low as 6.7 seconds, well over normal for a mainstream film, but far from a work dominated by long takes. (We will return to this in the third article.)

A similar alternation between two modes can also be found in the film’s tone. Mitchell mostly sticks to his limited palette, but time and again he breaks the pattern. Thus we are suddenly presented with lyrical interludes, for example the scene where the camera slowly approaches Jay doing her make-up, before it ends up in a fetishising, lingering close-up of her in the mirror, looking like a melancholy princess. Without any further ado Mitchell simply takes a break from everything to do with plot for all of 69 seconds. It Follows also contains brilliant stand-alone ideas, like fastening the camera to the wheelchair to which Jay is bound when she meets her first Follower, so when Jeff drives the chair away the camera is shaking in tandem with the chair, immersing us completely both in her predicament and the strangeness of it. Furthermore, Jay’s awakening at the hospital is a masterpiece of sustained “making strange” or alienation.

6. The Follower as metaphor

The curse is transmitted through sex. In her review, Britt Sørensen also touches upon sex as a rite of passage and adult life as something frightening coming towards the characters in the form of the Follower (most of its bodies are adults). The current bearer of the curse will always see the Follower face to face, and what is metaphorically coming towards them is adulthood’s depression or eeriness. As unrelentingly as the Follower, adulthood will arrive – and among other things crush innocence – and the film’s last scene and the Dostoyevsky quote just before also suggest the Follower as a metaphor of our equally inexorable death. In some cases the Follower’s bodies also kills their “children”. Additionally, the film evokes a theme of uneasy relationships between generations already in the prologue, when the soon-to-be-killed girl apologises for her bad behaviour towards her father in a last phone call.

There is also another rite of passage in the film: Jay and Paul are reminiscing about the time they found porno magazines as children, paging through them totally in the open, to great consternation when adults discovered them. The children were just laughing at the magazines, because “We didn’t really know how bad it was.” The event led to both of them receiving “sex education” from their parents the next day, in a transition from childlike innocence to a more adult (and shame-infested?) world. (Is it a coincidence that it is precisely the moment when sex education is mentioned that the Follower enters the house, through breaking the kitchen window?) Later Paul, the one who raised the issue of the porn, finds another pile of such magazines inside the house where the teens are looking for Jeff’s identity. But now the innocence about the magazines from their childhood is definitely transformed into something dirty and coarse, through both their knowledge of the curse and the surrounding mood of the “degenerated”, run-down house.

All horror movies are about fear, but It Follows can also be interpreted as a metaphor for fear of fear itself. To people afflicted with anxiety disorders, the fear of getting panic attacks may be as crippling for the quality of life as the fear itself. Mitchell consistently plays on the fear that the Follower may be anyone (or no one) of the people present in the studiously everyday scenes, so that Jay is in constant fear that the Follower/panic attack can strike her. (The dialogue in one of the films Paul watches on TV comments on this: “Almost sounds like a girl “; “A girl?”; “Perhaps – or a monster.” It also provides insights into Paul’s own situation, humiliated by the girls: “Stop teasing him, he’s in love.”)

It Follows is also about self-preservation. One can get rid of the curse by giving it to others through sex. Jay is reluctant to do this for a long time, but after an especially horrific experience, any qualms and moral objections are thrown to the four winds, and as if in a state of shock, she starts swimming towards three young men in a boat. In an inventive, stimulating turn Mitchell refuses to clearly show what happens. In a similar way the film merely suggests in another scene that one of the characters ponders giving the curse to some prostitutes. Mitchell’s strategy of suggestion, however, has a concrete function: The film’s “denial” reflects the fact that Jay would rather not think about what she has just done – in practice she has killed one of the men in the boat to save her own skin.

Jay’s boyfriend, who from the outset has planned to just use her to get rid of the curse, appears at first sight as a cruel person, but self-preservation drives him too. He shows more concern, however, than in the other characters’ own “transmittals”. In fact he takes great pains to explain to Jay, the next one in line, what the curse entails and how she can best survive. (True, it is in his own interest that the next one survives, since otherwise the Follower will just return to him – and in the film’s own interest, since it is a convenient way to explain the concept of the Follower to the audience without it feeling as a too-obvious block of exposition.)

7. Decay as a Follower

A recurring motif is the driving scenes, and during those Detroit’s social situation gradually infects the film as a thematic aspect. The city faces enormous economic difficulties, and large areas are marked by abandonment. (The city’s misery also plays a role in another recent film, Only Lovers Left Alive by Jim Jarmusch.) The film lingers on desolate areas of the city, marked by wretched homeless figures (almost always dressed in black), and run-down sections of the suburbs.

In addition to increasing the film’s general mood of emptiness and inhumanity, one can look at these areas as a metaphorical Follower that slowly creeps closer to and devours the city, or as an expression that entire areas have been devastated by Followers. Decay is also an issue in Jay’s own backyard, in her swimming pool:

Later the teens are inside a run-down house – in a residential area that looks like an abandoned, degenerated version of their own suburb – hunting for Jeff’s real identity:

In a scene towards the end, decay has reached her house in full force:

The hand belongs to Kelly, and we shall allow ourselves a short glimpse of one of the film’s many sudden lyrical turns, where a gliding camera at last comes to rest at Jay:

From now on the article is going to spoil central parts of the plot and its resolution.

8. The Followers

An important reason that It Follows feels so disturbing, is the fact that the Followers appear solidly anchored in everyday life. Their appearances are staged with some kind of reticent virtuosity, the camera almost accidentally capturing them. In an early scene, before Jay even knows about the curse, she is having dinner with Jeff:

Is the background figure a Follower? It is not unlikely, and it is conceivable that it refrains from attacking Jeff at the restaurant to avoid attention. At the same time the event has a stimulating ambiguity, since the visual composition of the scene’s end suggests that this is something that takes place inside Jay’s mind, some kind of inner fear or anxiety. This is curiously echoed in the scene where Jay discovers a Follower in the kitchen:

In this scene the phone seems to symbolise some sort of communication with the supernatural.

Most of the Follower bodies are unknown to Jay, but the horrific apparition that turns up at Greg’s cabin seems identical to the boy we have several times seen spying on her:

The boy is always dressed in red. Is he in cohorts with the Follower, or just an ordinary but curious neighbourhood boy? It is a bit strange that he is constantly turning up. On the other hand, he could be a human version of the Follower, a thematic parallel: a stalker-like type of person. The same goes for Paul, who is constantly hanging around Jay, without being particularly welcome, but waiting for his chance. It is therefore interesting that It Follows creates a parallel between Paul and many of the Follower figures:

The very first time we see Paul in the film he is knocking on Jay’s door. This happens in the scene where Jay is introduced: the camera captures Paul in the background, while on its journey towards Jay in the pool in the backyard. The parallel is very subtle – when we see the film for the first time we don’t even have an idea who Paul is at this point – but it is undeniably present.

9. The absent parent generation

The teenagers of the film are completely left to themselves to solve their problems. Exactly like in The Myth of the American Sleepover the parent generation is almost completely absent. In both films this is so strictly executed that we hardly see the face of any adults, at least not in closer shots. It almost comes as a shock when we see Jeff’s mother in close-up after Jay has rung the doorbell – the exception that proves the rule. (Incidentally, the mother looks quite similar to one of the few adults whose face we do see in American Sleepover).

In several scenes there is an undercurrent of yearning for childhood in connection with the parent generation. During the drive to Greg’s cabin, he says he loves to go there because his father used to take him hunting up there. When Jeff and Jay go to the cinema, they play a game: of the other people around, whom would they like to trade places with in life? (This would entail a change of body – a small allusion to the Follower’s constantly shifting appearances?) Jeff surprises her by having chosen a child instead of her candidate, a man standing with a beautiful woman:

The strategy of absence also goes for such a potentially important character as Jay’s mother (the father is totally out of the picture in this family.) Except for two scenes we soon shall look at, the mother is present in only three situations in the film (all the wine bottles and glasses associated with her suggest that she has an alcohol problem):

The following scene comes right after Jay’s intercourse with Paul, late in the film. The mother is supposedly trying to comfort the sorrowful Jay, but considering the parent generation’s position in the film, her sudden presence seems almost sinister:

This is very clearly an extraordinarily subtle point that is only supposed to dawn upon us when we revisit the film. (It completely escaped this author on the first two theatrical screenings – a screener was required.) The photo is shown up close only for a moment and the Follower is displayed at close range in only one shot during the climax. Incidentally, the green colour of the swimming hall wall matches the colour of the father’s jacket (and the green linen on Jay’s bed just before also participates in this colour chain). The father’s body is also the reason why Jay refuses to tell Kelly what she sees when the Follower turns up.

This particular Follower body makes the parent generation not only culpable through their absence, but symbolically an active part in the destruction of the younger generation. This also lends additional depth to the incestuous event in It Follows, namely the shocking scene where the Follower destroys Greg, by appearing in his mother’s body and fuck him to death.

The father, however, is also present in another photography (see below). Earlier in the film we see it attached to the mirror while Jay is laying her make-up before the date with Jeff. The position suggests that Jay is closely connected to her father (and she is probably the little girl in that photo). We see the same picture later, when Paul is in Jay’s room and conceives of the idea to lure the Follower to the swimming hall. The picture of the father is just below a photo of Jay in the same hall, making the father photo serve as foreshadowing in two stages: first as a general harbinger, and then as foreshadowing of the very specific connection between the father and the Follower in the climax. The picture of Jay also connects the swimming hall to the temporary pool in the backyard, which Jay used just before.

Then on to the first photography scene with the mother:

This is likely to be Jay’s grandfather. The incestuous element thus appears in escalating order in It Follows, and as a culmination of the two last Followers. Like the curse is passed on from person to person in a chain, the parents’ problems are symbolically inherited from one generation to another.

10. The neurotic and the hopeless

Seen in a way it seems to encourage, It Follows is an utterly sad and bleak film. It lingers on open spaces devoid of human beings, on decay and indescribable anxiety, and is dominated by the monotony of the many recurring motifs and devices. Here, for example, the incessant car driving, in interplay with the often despondent film music, forms some kind of melancholia of repetitiveness. The mood does not lighten after the Follower is ostensibly vanquished, rather the opposite. The scene where her mother “comforts” Jay is already mentioned. It is followed by the film’s perhaps most dismal situation, where Paul ponders transmitting the curse, observing two haggard prostitutes under a leaden sky surrounded by a post-industrial wasteland, while the film music’s main theme slows down into a plaintive murmur.

While death in the shape of the Follower constantly creeps closer to us, the film emphasises that our human condition is unchangeable. When Paul finally has slept with Jay near the ending, both sadly shake their heads at the question “Do you feel any different”. On the film’s surface level they ask themselves if they feel different now that the curse has been transmitted from Jay to him. But at a metaphorical level neither the rite of passage to the adult world through the intercourse, nor Paul’s now-fulfilled dream of possessing Jay, seem to have led to any change at all in how they experience the world. The intercourse, by the way, is executed with a visual accompaniment of an apathetic camera gazing out into the backyard, ready for a possible Follower to turn up, while the rain is hammering down, as a reminder of the climax at the swimming hall.

Furthermore, this sex scene starts with a shot of a barricaded door, where the “running” light from the rain reflected on the door is a direct reference to the play of light on the swimming hall interiors:

After Jay had sex with Jeff early in the film, she gives a small speech while we see her red fingernails poetically against a tiny flower. The speech is sad enough in itself, but the fact that it is immediately followed by an utterly treacherous, brutal assault – Jeff sedates her with chloroform – speaks volumes about the film’s tone:

It’s funny. We used to daydream about being old enough to go on dates and to drive around with friends in their cars. I had this image of myself holding hands with a really cute guy, listening to the radio, driving on some pretty road – up North maybe, where the trees start to change colours. It’s never about going anywhere really. It’s about having some sort of freedom, I guess, and now we’re old enough, where the hell do we go?

It is tempting to see this utterance in connection with all the car drives in the film – in fact, at one point they literally go “up North” to Greg’s cabin – where all the movement still does not lead anywhere. One of Yara’s Dostoyevsky quotes is also interesting in its fatalism, and is illustrative of the girl in the prologue, who has resigned completely, just sits waiting for the Follower to come and kill her:

I think that if one is faced by inevitable destruction – if a house is falling upon you, for instance – one must feel a great longing to sit down, close one’s eyes, and wait, come what may.

The Dostoyevsky passage Yara reads aloud in the penultimate scene, as if in some kind of conclusion, punctures any hope:

When there is torture, there is pain and wounds, physical agony, and all this distracts the mind from mental suffering, so that one is tormented by the wounds until the moment of death. And the most terrible agony may not be in the wounds themselves but in knowing for certain that within an hour, and then within ten minutes, then within half a minute, now, in this very instant – your soul will leave your body, and you’ll no longer be a person, and that this is certain. The worst thing is that it is certain.

Mitchell’s vigilance in form lends It Follows a neurotic dimension. Except for the early scene where Jay and Kelly stroll by the road, virtually every transport scene at foot is shot in the same fashion, where Mitchell alternates between shooting the characters from behind and facing the camera. This is illustrated in the following slide show:

The straight line is another motif of the film, suggesting a lack of choices. This is from the opening scene, which constitutes part of the film’s small prologue:

Soon Jay is introduced, also this in a long take (43 seconds):

The following slide show shows the motif of the straight line in its full extent, often generated by the car driving:

The final Dostoyevsky quote is followed by a scene that feels like an epilogue or coda. As if emphasising the lack of a positive resolution, it mirrors the prologue by the almost demonstrative sound of bird twittering against a backdrop of silence, and by the straight line again being dominant:

*

The characters attempt to get away from the Follower by passing the curse on to others or move geographically, to “buy time,” as one of them puts it. But the Follower always returns. We live in only one direction, forwards in time. There is only this way to go, but like It Follows suggests, it leads nowhere. We can only buy some time, before death overtakes us.