What makes a film festival truly great? Searching for clues at Karlovy Vary’s 50th Anniversary

Karlovy Vary 2015: What makes a film festival truly great? Searching for clues at Karlovy Vary’s 50th Anniversary, we stumbled upon an even bigger question: ‘What makes us truly free?’

KVIFF’s anniversary seems a fitting moment to celebrate its post-communist renaissance as an expression of human freedom and artistic endeavour, except no sooner is one tyrant deposed than another steps up to take its place. Now it’s the turn of another big C, commercialisation, well-equipped with its own form of dogmatism. A new struggle for freedom has only just begun. Still, there are grounds for optimism, deep in the soul of this remarkable festival…

The festival – of film or anything else – is a powerful modern symbol of freedom and, at its best, an astonishing outpouring of human creativity. It depends on a delicate balancing-act between order and spontaneity, however. That’s why tyrannical regimes have always been much better at parades and rallies. For the classic cinematic illustration, see Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will, from 1935.

We shouldn’t be too surprised that the Eastern Bloc’s own top-rank film festival took shape in the aftermath of foreign occupation and war, or that it should have suffered, in turn, under the yoke of a new hegemon, the emerging Soviet superpower. So this year’s 50th ‘anniversary’ of the festival in Karlovy Vary seems a fitting moment to celebrate its re-emergence and triumph as an expression of human freedom and artistic endeavour.

That is, it would be, if a new form of tyranny had not long since taken hold. For this is one of the most powerful tyrannies of all, the tyranny of commercialisation, especially virulent when complemented by its trusty companion, the cult of personality.

There’s something about a festival that’s always resistant to tyranny, however, and perhaps never more so than in the hands of the exuberant Czechs. Thus the festival continues to struggle – and with some success – to be great. The source of its burgeoning greatness is another matter. Here we may need to look beyond the usual suspects: the organisers, assorted dignitaries, international superstars and the like.

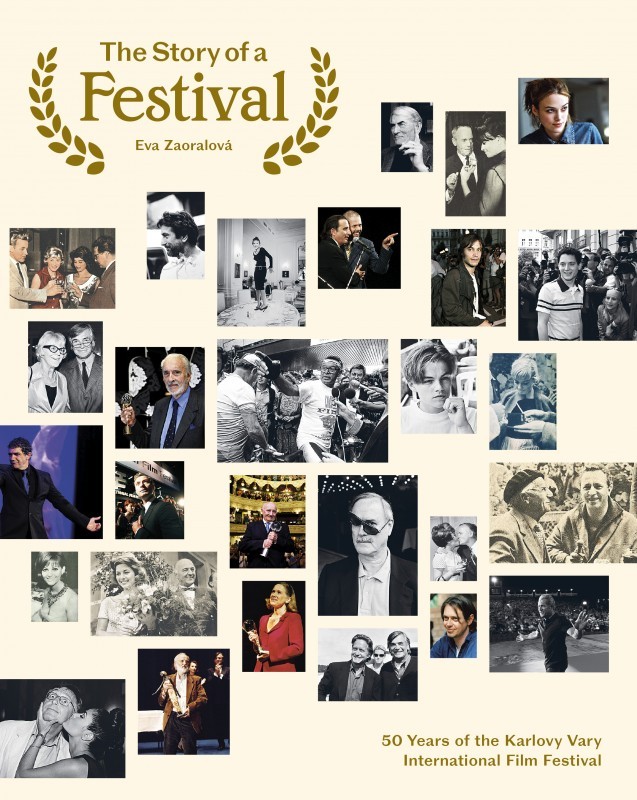

You can read the ‘standard’ history in Eva Zaoralová’s The Story of a Festival, published in both Czech and English to coincide with this year’s celebrations. Here’s your basic ‘Reader’s Digest’ condensed version:

- The festival was first arranged in August, 1946, before many of its international rivals

- Only to chafe under the yoke of Communist oppression and ideological dogma, which showed no signs of weakening before the death of Stalin in 1953

- From whence the festival thrived for a while in the prelude to the legendary but short-lived Prague Spring of 1968, despite having to endure a biennial rotation of the A-list event to Moscow from 1959 onwards (which explains why the 50 instalments spanned nearly 70 years)

- Until the invasion and crackdown of ’68 brought it to the brink of extinction

- Only for the surprise end to the cold war and demise of the Eastern Bloc to allow the festival to live happily – and annually – ever after.

It’s a heart-warming story but one that demonises the past and romanticises the present. I want to provide a more nuanced account, laced with more contradictions than happy resolutions, more in the style, strangely enough, of a typical festival film. The motive force behind a festival can be many things. The festival miracle is what it may achieve in spite of the various, and often dubious, motives that may have set its wheels in motion.

KVIFF was born from the watershed of war and its backlash, which took the form, in typical fashion, of patriotic self-assertion. In times like these, unfortunately, it’s a thin line between national feeling and xenophobia, and especially in reaction to a war as extreme as this one, more undiscriminating and wilfully punitive than anything in living, or perhaps any other kind of, memory. This helps explain, at any rate, the otherwise unlikely choice of location for a new film festival: a sleepy old spa town, favoured by landed aristocracy for generations as their peaceful getaway of choice.

What nevertheless recommended Karlovy Vary, as well as its even more modest neighbour Mariánské Lázně (aka Marienbad, the co-host in the earliest years), was a location in what Hitler and his fellow travellers preferred to call the Sudetenland. Its predominantly ethnic-German population had provided the pretext for the annexation of Czechoslovakia in 1938. Two important and related things happened in 1946, only one of which is mentioned in the ‘official’ history. One was of course the establishment here of a festival designed to celebrate Czechoslovakia’s newly nationalised film industry. The other was the organised expulsion of most of the region’s ethnic Germans: By 1950 almost three million had disappeared (in some cases literally) on a national level, leaving less than 200,000 behind.

The celebrated Czech writer, Vítězslav Nezval, for one, clearly saw the festival as part of a life-affirming response to German aggression. He wrote, ‘We want to raise a flag in the beautiful corners of our country where, until recently, the hostility towards our nation had its most unassailable bastion, a symbolic flag of new beauty and the new spirit of contemporary film production both at home and abroad.’

The socialist seizure of power soon after the war established a Soviet-friendly regime in Czechoslovakia. It drained the life out of the festival in sponsoring pro-Soviet and anti-Western orthodoxy, and a programme of films that struggled to fill the venues. One still can’t help being struck by the overblown references to totalitarianism in The Story of a Festival. Whatever its long pedigree totalitarianism has always been a much too polemical concept, implying a degree of deep social control more in keeping with Orwellian fiction than any real political practice, even at the height of the cold war. Nevertheless, the Czechoslovakian state did fall under the thrall of the Soviet Union after the war and, in the years that followed, became increasingly authoritarian.

The socialist seizure of power soon after the war established a Soviet-friendly regime in Czechoslovakia. It drained the life out of the festival in sponsoring pro-Soviet and anti-Western orthodoxy, and a programme of films that struggled to fill the venues. One still can’t help being struck by the overblown references to totalitarianism in The Story of a Festival. Whatever its long pedigree totalitarianism has always been a much too polemical concept, implying a degree of deep social control more in keeping with Orwellian fiction than any real political practice, even at the height of the cold war. Nevertheless, the Czechoslovakian state did fall under the thrall of the Soviet Union after the war and, in the years that followed, became increasingly authoritarian.

Putting the polemical caricature of the totalitarian myth aside, let’s ask ourselves what political conditions really meant for the festival and, by implication, other cultural activities of the time. Reading between the lines, for all its challenges this was a thriving festival, no passive receptacle of a one-sided totalitarianism. Rather its activities through the years betray a dynamic of repression, yes, but also resistance. Indeed it was the latter that often seemed in the ascendancy, exposing ‘the authorities’ to continual – albeit veiled – ridicule.

There is such a thing as ‘people power’ and it can never be entirely extinguished. Even the Ancient Romans had to endure the occasional slave revolt. The selection-committees and prize-juries may have been infiltrated by ideologues, with disastrous consequences for the competition films, but, almost according to the law of equal and opposite reaction, many good, foreign, that is, non-Soviet and, indeed, Czechoslovakian films were featured in the non-competition programme. Moreover, these were the screenings to which audiences flocked in their droves, neglecting the official selections, and leaving their venues conspicuously and embarrassingly empty.

Plus ça change! Even today, the competitive programme is probably the last place you’d go looking for the best movies. So what did ‘the authorities’ do? They opened their doors to all and sundry to come and watch the competition films, even bussing people in from the nearby mining-town of Jáchymov.

Is this totalitarianism or is it just the same, sorry old story of the state, which Marx long ago suggested is destined to relive the tragedies of the past a second time over, as farce? Who were the real winners, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic or its people, enjoying, with appropriate measures of irony and pilsner beer, a free film, albeit probably not an especially good one? The contrast with present-day Karlovy Vary is illuminating. Many locals complain of feeling excluded from the festival. No longer encouraged to participate as in times of old, they lament the practical obstacles put in their way, such as the apparent necessity of queuing long hours for tickets together with hordes of ‘backpackers.’ From the perspective of the ordinary people of Karlovy Vary, not everything has changed for the better.

Much of the Communist-era spirit of the festival was in evidence in Miroslav Janek’s impressive documentary, Film Spa, prepared for its premiere at this year’s celebrations. Particularly striking were the clips of playful, witty and irreverent filmmaking, taken from the classic crowd-pleaser known as Festival Moments. In their heyday in the mid-1960s the ‘moments’ were featured every day throughout the festival. If the few selections seen here are anything to go by, they represent a fascinating historical archive. Fast turnover and relatively limited distribution (that is, to festival filmgoers) seem to have granted the filmmakers considerable license. Their efforts are testimony to the resilience and ingenuity of the creative human spirit. Somehow it will find its space and its venue, wherever that may be. By hook or by crook, it will find a way to express itself.

A massive drawback with authoritarian regimes is their unpredictability, it must be acknowledged. Increasing liberalisation at a national level eventually provoked a backlash, the infamous Russian invasion and crackdown of 1968. Henceforth there would be no more ‘moments,’ as an increasingly constricted festival entered a long period of decline. Even this can be overstated, however. Real resistance at the very cusp of what was euphemistically referred to as ‘normalisation’ was in evidence in the hard-fought decision to give the festival’s top prize in 1970, not to the organisers’ favourite, By the Lake (1969), from Soviet director Sergei Gerasimov, but to the kitchen-sink masterpiece Kes (1969), directed by the British newcomer, Ken Loach. In so doing the jury can take some credit for the discovery of a major new talent of world cinema.

The end of the cold war turned out to be no panacea on the other hand. The breakdown of the old order brought its own problems. First came the honeymoon, however, the probably rather marvellous festival of 1990. Its iconic image is that of the filmmakers Juraj Jakubisko and Miroslav Ondříček arriving by bicycle, reputedly all the way from Paris, a metaphorical return from exile and one of the greatest red-carpet entrances of all time.

Still, there was trouble in paradise. With a little political manoeuvring, a rival foundation managed not only to establish a competing festival in Prague, but also to take Karlovy Vary’s coveted A-rating for itself. Political connections may have opened up an opportunity for the new kid on the block, but it failed to measure up to the task of organising a successful festival. For two years, 1995 and ‘96, KVIFF hunkered down and kept its show on the road, while its Prague pretender faltered. The following year the status of the Czechoslovak original was restored and, so the story goes, ‘they all lived happily ever after.’

It is possible to nod with satisfaction at the battle between KVIFF and the new Golden Golem concept in Prague and conclude that ‘God’s in his heaven and all’s well with the world.’ Didn’t the best festival prevail? Isn’t this, after all, an example of the universe unfolding as it should, exhibiting the modus operandi of our own beloved way of life: good old fashioned competition, the survival of the fittest, let the best man win, etc., etc? Well, yes, this tale of two cities probably does reflect a kind of global modus operandi, but it’s not quite as simple or as benign as we may like to believe.

Who wins this kind of game is probably mostly down to dumb luck, since what determines success is largely, on the one hand, what you’re already fortunate enough to have and, on the other, who you know that can offer you more. Such outcomes are not the product of a benign, invisible hand, à la Adam Smith, but rather that of privilege and patronage. This is not peculiar to the Czech Republic’s understandably chaotic transition to liberal democracy. This is capitalism as it operates pretty much everywhere, that is to say, in practice rather than in theory. Never mind the liberal mythology and the quasi-religious faith it has spawned in ‘the magic of the market.’

Still, KVIFF did prevail and its virtues and strengths as a kind of film institution certainly didn’t hurt. It is something special at the grassroots level that has ultimately breathed life into this project and lent it such a remarkable tenacity. Observers are regularly struck by the character of KVIFF as a kind of people’s festival – young people in particular. They add vitality and energy to the festival experience as audience-members, and work tirelessly behind the scenes as enthusiastic volunteers. In the words of Steven Gaydos, of Variety, Karlovy Vary isn’t really like any other film festival in the world. It’s younger, friendlier, easier and more joyful than any of the dozens of international film festivals I’ve attended.

Perhaps that’s because its roots are so deeply planted in a past where freedom of expression for young and old was rigorously opposed or meticulously monitored.’ Thousands of young people flood here every year, literally to a kind of film-camp, given that many of them will be living in tents. They share a sense of ownership, a notion that the festival continues at least in some degree to be for them, and to provide an expression of the freedoms that, historically speaking, could never be taken for granted.

Just as the life-sapping order inserted itself inside the festival’s own organisation in the dark days of 1970s ‘Normalisation,’ so it is, to a lesser degree, today. We can still see the vitality of the festival as a kind of human carnival working against the grain of the organisation and its norms. There is no better example, in this regard, than the strange case of Petr Folprecht.

He’s just the guy who takes down the mic-stand after the introductions, presentations or other formalities at the more ceremonial screenings, which are always scheduled in the biggest venue, the Thermal Hotel’s Grand Hall. Any direct acquaintance will tell you he’s much more than that, however. You will observe him perform his task with an air of astonishing gravitas, followed by a most ostentatious bow. The unfailing response of Karlovy Vary audiences is uproarious applause. Here is the cult of personality indeed – or perhaps its mirror image, or its nemesis in the form of an ironical echo.

The common lifeblood of a festival is imprinted upon the history that its living denizens have made together for themselves, and Folprecht and KVIFF audiences do share a history. He has entertained them by turning the performance of his simple task into a real performance. Aficionados might remember, for example, him handing his jacket to his dutiful and proverbial ‘beautiful assistant’ in elaborate preparation for the heavy lifting required.

Is he not a metaphor for the festival itself? He’s the object of repression – his jokes and routines have been curtailed – but he’s still there, alive and kicking. Indeed, he is adored – and remembered – from year to year by the crowds: the irrepressible spirit of human creativity, the heart and soul of the true festival. He will continue to annoy the organisers by getting a warmer audience reception than most of the invited celebrities on parade. Long may he do so! They may clip his wings but they cannot – dare not – deny him the gift of flight.

On opening night the festival had organised a party – open to all – a fitting tribute and thankyou to the ordinary theatregoers who have been its ardent supporters through the years. I abandoned my proper place in the exclusive ‘Meeting-point,’ reserved for accredited representatives of film industry and media, and ventured down into the grounds of the Thermal Hotel to join the throngs. This was at once terrifying and exhilarating, too many people crammed between brutalist architecture (what one commentator dubbed ‘a potato in a jewellery box’) and the immortal river. In just a few hours the festival had become an unpredictable, seething mass of undifferentiated humanity. The tell-tale signs were the overflowing bins, the pathos of ‘glad-rags’ and glamour lost in the thrall of the faceless crowd, and the unremitting din.

Every so often a sort of excitement or panic would take hold, like an epileptic seizure, when the crowds threatened to stampede in one direction or another. I hadn’t seen anything like this since the glory days of ‘Red Ken’ Livingstone and the Greater London Council, but back then I was younger – and more fearless. ‘There are just too many people,’ I remember saying to myself, ‘Someone could get trammelled and killed under the crowds – it would only take a bit of bad luck. That someone could be me!’

Then, all of a sudden, a movement, a veritable phalanx, is coming towards me like a living, breathing tsunami, threatening to sweep me away. For the barest second I try to hold my ground and I can feel the ‘people power’ at its most literal, physical and kinetic, like the force of nature it truly is. Then I submit to its guidance, go with the flow, and just allow myself to be carried along. We move as one now, in perfect harmony, glorious and dangerous like a human flying machine. Is this what it means to be free?