Lady in the Water, Part I: A reappraisal

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This reappraisal of Lady in the Water is in two parts. This first part is about the film in general. The second article explores the film’s extensive self-reflexivity and visual stylisation. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

It was Shyamalan’s misfortune to make a somewhat goofy fantasy at a moment when critics were poised to puncture his reputation.… I hope that once the chatter fades away, people will appreciate the virtues of Bamberger’s book and of Shyamalan’s film.

– David Bordwell, on Michael Bamberger’s making-of-book “The Man Who Heard Voices”, and M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water.

Reading about M. Night Shyamalan these days is a depressing activity. Following the rather sharp drop in quality, and not least in ambition, starting with The Happening (2008), open season seems to have been declared. Malicious comments, delivered with no end of nastiness and gloating, can be found on the Net, it seems, virtually everywhere his name is mentioned. (In fact, it appears obligatory these days for the bashers to make fun of that very name.) It all has the highly distasteful air of people ganging up to kick someone who is already lying down.

There is even a myth that seems to be spreading that he was never more than a one-hit wonder in the first place, as if his breakthrough work The Sixth Sense were some sort of fluke. All of the above is a great disservice to a man whose five films from The Sixth Sense to Lady in the Water represents a body of work that is as interesting as any American director in the first half of the 2000s. The backlash in earnest, however, especially from critics, started already with the fourth film, The Village.

A lot of the objections against several of these five films – both at the time and in the current atmosphere of retrospective devaluation – seem rather unfair. Some try to torpedo films that are clearly intended as non-realistic metaphors with literal-minded and prosaic objections. Others seem to second-guess the quality of the material due to the enormous box office takings of many of his films or the amount of marketing involved. Evaluations are influenced by real-life perceptions of the director as egocentric and self-promoting, as if Shyamalan were the only artist ever to display such traits. These films’ reuse of themes, motifs and plot elements is often seen as signs of creative poverty and desperate clinging to formula, even though such a singularity of vision is usually regarded as a virtue in an artist. There seems to be an almost obsessive urge to judge his films on the quality of his patented plot twists alone, as if all other artistic aspects of cinema besides “story” have magically been made inconsequential just by introducing a twist. (Quite a few of these attitudes are present in this attack on Shyamalan, in which the author even manages to hold the director’s loyalty to his home city of Philadelphia against him.)

In this article I will try to avoid all this noise and go back to the basics. I will analyse his work, in good faith, as any other film, by any other director. Any issues extraneous to the films will not be considered.

(Michael Bamberger, who had full access to the preparations and shoot, has written a very interesting and nuanced account of the making of Lady in the Water, “The Man Who Heard Voices: Or, How M. Night Shyamalan Risked His Career on a Fairy Tale” (New York: Gotham 2006). The paperback edition contains a new foreword by David Bordwell, who had earlier written a defence of the book and the film. He felt the book was misrepresented by reviewers and, although he finds faults with it, he thought the film’s extremely hostile reception inappropriate and neglectful of its qualities. I also recommend this long analytical review (in PDF) by the American writer Colleen Szabo.)

Lady in the Water

This article is about Lady in the Water, the first of two articles about the film. Since it represents the culmination of a series of works that can be regarded as one long film, however, I will from time to time connect it to the previous works.

In this first article I want to cover a variety of aspects of Lady in the Water. I will first start on a personal note about my own first encounter with it and contrast my experience with its exceptionally hostile reception. Then some unifying lines between the five films in the series will be drawn up to provide a thematic foundation. After that I will walk through some early scenes and address issues that might have been perceived as problematic, for example its constant tonality shifts and the importance of context in understanding the film. Since Lady in the Water is a curious mix of diverse elements that often exist side by side, I will then examine how it mixes monumental themes with mundane settings and behaviour, and how it is both serious and comical. In fact, the various forms of humour that permeate the film will be a running subtheme in all of the above. Then the central theme of childlike innocence will be explored in depth. The main body of the article ends with a discussion of the film’s weaknesses and strengths. In an appendix I will suggest how reading the film as a fantasy role-playing game may be illuminating. (Incidentally, this appendix may be useful for readers who want to refresh their memory of the plot.) A second appendix lists some additional points that do not naturally fit into the article but deserve to be mentioned.

The second article will discuss Lady in the Water‘s possibly most important theme, namely its self-reflective nature. That article will end with a focus on its visuals using frame grabs, for example a reflection upon the film’s stylised depiction of fear and ritual, and its very beautiful, tender ending.

It is my hope that through these writings I will have demonstrated that Lady in the Water, contrary to its widely held perception as a totally baffling heap of incoherent ideas, actually is a well-thought-out and highly interesting work, and that in essence it displays much of the same methodical approach that marked the previous four films of M. Night Shyamalan.

A personal journey

First I have to come clean and tell you that I love this film. Not right away, mind you – my impression of the first viewing was one of highly amused confusion. My amusement was with the film, however, rather than at it. And the rage, which seemed to oscillate within a narrow band from white hot to red hot, that many felt towards the film has always mystified me. Critics insisted that the whole thing was impossibly pretentious, while being completely blind to the playfulness that permeates the film.

To me, this sweet little film contained some of the most exquisitely absurd, whimsical and childlike humour I had ever experienced. Especially the scene where the hero has to pretend to be a child in order to coax a bedtime story out of a Korean dragon lady must be one of the most extraordinary moments of happiness I have ever experienced in a movie theatre. The red hot/white hot crowd seemed to hate that scene intensely.

I enjoyed the film’s fantastically unpredictable ride, embracing Lady in the Water as if it were a Zen-like riddle not to be immediately understood, at least not on its first viewing. In my view the above scene was pure genius, in its mix of utterly disarming sweetness, playfulness and an outrageously exaggerated (and definitely intentionally so) manifestation of an apparent theme of adults behaving/becoming like children. Another scene, where a little boy interpreted momentous signs from the universe through childish drawings on cereal boxes was another moment of bliss. (I will get back to these scenes at various points.) Other than the pure entertainment value of the film, I had little idea of what I had seen.

I had limited experience with Shyamalan, but his previous film The Village, which I had seen only once two years ago, was one of my most hypnotic viewing experiences ever, although that as well was hard to get a grip on. So I went to see Lady in the Water again, found it as funny as last time and the plot much easier to understand. On the third and fourth viewing something wonderful started to happen, in the form of a subtext gently rising from the film, a self-reflexivity of a nature that felt highly original and complex. Incidentally, through its foregrounding of play-acting, the above pretending-to-be-a-child scene fits squarely into that scheme. Quite a few other scenes, in fact, are executed with a similar free-wheeling “we’re just playing here” attitude. These four viewings took place in rapid succession, because almost all the reviews were extremely hostile and the audience during screenings so limited that I realised the film would not last more than a week (here in Oslo, Norway). The strange thing was that although few critics could see any humour in it, many in the audience laughed heartily, in exactly the right places, and clearly with the film, not at it.

Now that I have revisited the film seven years later, and in a newly acquired context of Shyamalan’s four previous works, it may not be as excellent as those other films. (By its very different nature, it is hard to tell though.) I would argue to my grave, however, that Lady in the Water is a very interesting work. The few of us who like the film are buoyed by (or perhaps clinging to!?) the fact that it has been much more favourably received by French critics. After all, this is the country in the world that is the most serious about cinema as an art form. In fact, Shyamalan’s two most-maligned works at that time, The Village and Lady in the Water, were voted in among the ten best films of 2004 and of 2006 by Cahiers du cinéma, the world’s most prestigious film periodical.

The five senses of M. Night Shyamalan

The Sixth Sense, Unbreakable, Signs, The Village and Lady in the Water can be said to constitute one long film revolving around the same themes and motifs. (They are somewhat less evident in Signs, however.) Curiously, these five volumes are almost equally long, respectively clocking in at 107, 106, 106, 108 and 110 minutes. This chapter is partly a summation of points made by my fellow film analyst (and very good friend) Aubrey Wanliss-Orlebar, in a conversation I had with him about Shyamalan, published in the Norwegian film periodical Z, issue no. 4/2007, for which I was editor. I have added more points of my own. Furthermore, the films’ common subtext/discussion of pop culture is detailed in Appendix 1.

Faith, purpose, innocence. Faith, and grave doubts about that faith, is extremely central. There is also a constant emphasis on how faith at the same time is also a risk. Yet faith can lead to extraordinary human acts, which redeem the characters and lead them to their purpose in life. Innocence and childlikeness are also significant, magnified into all-importance in The Village, where the whole purpose of the community is to shield innocence from a violent world.

Mentor characters. There are always mentor characters that help others realise their true nature. This often turns out to be mutually beneficial because that very act will help the mentors themselves realise their potential. One of the characteristics of Lady in the Water is that it often contains “more of everything” from the previous films, so among its mentor characters we have: the sea nymph and the hero who will help each other realise themselves; the Korean mother who tells large chunks of the bedtime story; the writer who will inspire a future leader to change the world; the tenant Mr. Leeds who will inspire the hero at a crucial moment; the false mentors of the film critic and the first incarnation of The Interpreter; and many more.

Secrets, revealed through elaborate rituals. On a meta level, we have the secret of Shyamalan’s twist endings, revealed through the “ritual” of watching his films. The sense of his films as rituals is also greatly enhanced by the repetitions of, and variations on, a large number of recurring motifs, often across several films. There is no specific twist ending in Lady in the Water, but the plot has so many unexpected turns, detailed in Appendix 1, that one could say that it is a collection of twists. On a more conventional level, here are some main secrets: In The Sixth Sense: the true nature of the mentor and of the boy’s seemingly mental problems. In Unbreakable: the abilities of the hero and the means used by his mentor to find him. In both films, the characters gradually approach the truths through a ritual of various self-doubts and crises. More specifically, in the first film the mentor tries to lure the secrets out of the boy in several stages: through the rituals of a mind-reading game, free association writing, performing a magic trick, and the telling of a bedtime story. In Signs: the true nature of the crop circles, the aliens and their invasion, and the significance of the last words of the hero’s dead wife. In The Village: the nature of the monsters in the forest around that film’s community, the real relation of the community to the outside world, and the blind heroine learning her own capabilities while negotiating the secret and overcoming her terror. In this film the secret is more ritualised, because it is maintained on the level of a community by a council of elders – deceitful mentor characters. In Lady in the Water the finding out about the secret is ritualised from one end of the film to the other and there is a whole panoply of them: The secret of the hero’s past. The sea nymph should keep the nature of her community from the humans. She is not to know until a certain stage that she is very important to that community. Her presence is to be kept secret from most other tenants. The other characters are trying to understand the secrets of her world to prevent her from dying and enable her to return. The little boy’s hidden ability to read the sublime from the ridiculous. The Korean mother’s secret of the bedtime story. The writer keeping the secret of his future fate from his sister. And so on and so on.

Withdrawal from society. The heroes have all seen no other recourse than to withdraw from the world, for reasons detailed in the next item. In The Sixth Sense the boy has made a makeshift tent inside his bedroom to hide from ghosts. In Unbreakable the hero, in denial of his real powers, has withdrawn into a self-imposed limited existence. In Signs the family barricade themselves in their house for fear of the alien invasion, and the entire invasion is seen from the family’s rural, limited viewpoint. In The Village a whole community has withdrawn from society. In Lady in the Water there is yet another community in withdrawal, but here in a more metaphorical sense, in that the camera, except for two shots, never leaves the apartment building and its backyard. Seemingly poised between a city street on one side and a forest on the other, the location also has a slightly unreal, allegorical feel of something just existing as an arena to play out the story. Finally, the hero and at least one other tenant have definitively withdrawn from society, in every sense of the word.

Politics, violence and bleakness. One of the most astounding things with Shyamalan of this period is that he managed to make such bleak films in the format of top-of-the-line budget, commercially mainstream Hollywood films, and, to top it off, for a company within the Disney conglomerate. In these works there is a sense of an alternative reading of American history, with a particularly dark and critical representation of its society. For example, when the boy who sees dead people in The Sixth Sense is at a courthouse, rather than a place upholding justice, he sees it simply as a place where they hang people. Crimes, on or off screen, are depicted with all their moral squalor and darkness, and in the “crime-free” Signs, the priest has lost faith due to a particularly cruel, bloody and meaningless car accident. Contrary to most mainstream Hollywood films, where crime is normally treated as something to excite the audience, Shyamalan depicts them with a more distant and reflective view. A direct concern in the first two films, in the last two they become enmeshed in a more allegorical, larger narrative picture.

Panic attacks. In The Sixth Sense‘s opening scene, in a mild form, when the hero’s wife, suddenly unnerved, runs out of the cellar. Then stronger as the boy flees the ghost in the kitchen. Even stronger in Signs, where the hero runs away from aliens through the cornfield, and more extensive still in The Village when the blind girl loses her self-control in a forest of hostile monsters. As befits a bedtime story, Lady in the Water presents a child-like take on this when Mr. Heep and the sea nymph are gripped by uncontrollable fear when first meeting the scrunt. (Although not caused by an enemy, the hero of Unbreakable panics when becoming entangled in the swimming pool.)

Cellars as important locations. A cellar scene opens The Sixth Sense and the protagonist sets up an office down there, and experiences a conceptual breakthrough. In Unbreakable the hero finds out that he has super-strength in the weightlifting scene. In Signs there is an extended sequence where the family barricade themselves in the cellar during the alien attack. The motif is less pronounced in The Village, but the characters hide in the cellar when monsters roam the village. In Lady in the Water the film critic is killed there, Story is revived and Mr. Heep finds out that Vick Ran is a writer.

Denial. In The Sixth Sense the hero is in denial of his real status and in Unbreakable of his real powers. The priest in Signs denies the existence of God and for a good while the reality of the alien invasion. The elders in The Village refuse to acknowledge the existence of the modern world. (The motif is not as prominent in Lady in the Water.)

Children or childlike characters. Children play prominent roles in the first three films. There are childlike characters in The Village (Noah) and Lady in the Water (Story).

So Lady in the Water sums up, and in great excess, familiar themes and motifs. As the concluding work of the series, it is also fitting that it should concretely refer back, quite heavily, to the earliest instalments. In The Sixth Sense, the telling of the bedtime story (which finally got the boy to reveal his secret), the teacher whose childhood nickname was “Stuttering Stanley”, ghosts in the basement (Anna Ran says, “My mother said she saw a ghost once, in the basement”, connecting to her namesake Anna Crowe in the former film’s opening), translation (from Latin and Spanish), the red balloon exploding to great effect (plus other references detailed elsewhere in these articles) – all refer to elements in Lady in the Water. The links become particularly evident in Unbreakable, which is only natural since a core theme of both films is that ancient myths are real. Thus, in Unbreakable we have:

- the importance of water

- shots from underneath the water

- a swimming pool (and another one mentioned)

- drowning

- the hero saved from drowning and in both films by children/a childlike being

- the use of walkie-talkies

- seeking great meaning in the ordinary (comic books)

- the analysis of storytelling technique (to foreshadow who the villain is in a comic book)

- the hero’s hidden folder, on a high shelf, of newspaper clippings detailing his past and his tragedy parallels the diary in the later film

Early scenes and tonality shifts

As Bamberger suggests in his book, if Lady in the Water had been a smallish arthouse film instead of marketed with all the fanfare of a big studio production, its reception would probably have been more favourable. Shyamalan must take a lot of the blame here, because he was unable to let go of the idea of reaching the same mass audience as his previous four films. And as Bordwell writes: “If Lady in the Water had been made by an obscure East European director, reviewers might have praised it as magical realism and tolerated its fuzzy message of multicultural hope.” Finally, if no secret had been made of its weirdness and complexity before it was let loose on an unsuspecting world, things might have been different. I would imagine that many, critics and audiences alike, mentally “checked out” of the film at an early stage, and then sadly were unable to fully appreciate even the sequences that did not require any special effort.

So, if one is to get anything out of Lady in the Water, one has to accept that in many respects it refuses to follow traditional rules of storytelling. For much of its running time, at any time, without any warning, it may lurch from one tonality to another. Almost perversely, it is during the first fifteen minutes or so, where any normal film would have taken great care to establish a consistent tone to draw people in, that its tone is fluctuating most wildly. As if it were an enigmatic “art film”, no particular contract with the audience is attempted. I shall now walk through some early scenes to confront some issues that might have been perceived as problematic.

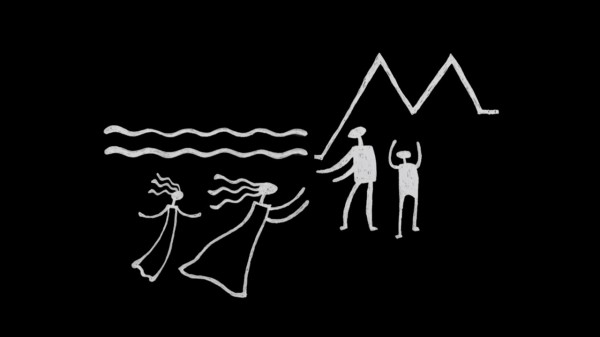

The film starts out with an animated prologue telling a seemingly utterly banal narrative, later revealed as a bedtime story, of how ancient Man in its greed parted with a community of wise sea nymphs. It is accompanied by a very solemn voice-over, strangely insisting on imposing great importance on the apparent banality. (On repeated viewings this prologue, in its hypnotic elegance and minimalist beauty, to the tones of James Newton Howard‘s soothing music, has turned into one of the highlights of the film, although the voice-over remains slightly grating.)

Then, suddenly, we are careening headlong into farce. A long scene, in just one take, shows a man in close-up involved in the lengthy business of doing away with an unseen bug. This is accompanied by a chorus of wailing women with exaggerated, silly Spanish accents. The man, who is called Mr. Heep and is the superintendent of an apartment building, has a strange stutter.

Already at this point, an uncomfortable question arises – are we supposed to think his speech impediment funny? No, although juxtaposed with a strange situation it can be, like when he is lying on the ground and stammering into it, when being confronted by the film critic after having just escaped a near-fatal encounter with a demon-creature. (Hey, with just one sentence of plot summary sounding so weird, how to deal with 110 minutes more of it?) Are the women supposed to be funny? On a very-low-comedy level, certainly, but the stereotype of a superstitious Mexican family shivering in fear is so impossibly broadly drawn that it, among other things, could be a diversionary tactic. They might be made out to be so stupid because we could not possibly consider them seriously as The Guild later, when the hunt is on to find tenants with the all-important magical abilities. It is similar to how Reggie, the guy who only trains one side of his body, seems by far the most brain-dead person of the building, but ultimately turns out to be dealt the pivotal role of The Guardian.

In the next situation we suddenly stare right into a close-up of the behind of a young Korean woman, who then starts to walk away, wriggling her hips in an exaggerated manner, clothes in bad taste, before ending up in conversation with Mr. Heep. Strangely, we do not see her face at all during the scene. Is this portrayal sexist? Frankly, I am not sure; this scene has always seemed very, very awkward. The only explanation I can offer is that, like Reggie and the Mexicans, Shyamalan wants to start her at a low point, because she too will come to play a pivotal role in the unfolding of the bedtime story.

Next, we see Mr. Heep in conversation with a pool man. This scene has a strange undercurrent, its subtlety quite masterfully handled by Shyamalan. While Mr. Heep seems almost humiliated, the muscular pool man asks questions in an interrogatory, faintly contemptuous and menacing manner, words clipped military-style. There are also longish, pregnant pauses in the dialogue. His general attitude to the pool problem seems to be slightly out of proportion to the ordinary setting, as if he was on an important mission of some sort. This appears to be one of the more subtle manifestations, possibly meant as foreshadowing, of the film’s motif of mixing the mundane and the (in this case just slightly) monumental, which we will soon go into.

What is interesting about all of these three one-take scenes is their play on the unseen. We neither see the bug, the Korean girl’s face and when the pool man with grave emphasis holds up something he has found in the pool filter, the camera swings with perfect timing to stop us from seeing it properly. Shyamalan showed a genius for playing on the unseen, in horror fashion, in Signs and The Village, but this is very different. Here he seems to want to establish a subtle tone of secrecy and holding back information, not yet grounded in anything tangible but possibly as foreshadowing of all the real secrets later in the film and of how the complete bedtime story will be held back, only to be revealed in stages. The latter is reminiscent, by the way, of how the protagonist in The Sixth Sense has to gradually tease out of the boy the secret of his problem.

Also, the choice of not showing the bug, the very raison d’être of that opening scene, seems to lend a certain artificiality and gentle undercurrent of play-acting to the situation. Paul Giamatti the actor only pretends, of course, that the bug is there. The exaggerated acting of the Mexican women only adds to the artificiality. All this ties into the film’s important theme of self-reflexivity, which will be dealt with in the second article. Furthermore, in a number of ways this scene foreshadows the appearance of the “scrunt”, the wolfish demon-creature: the women suggest that the bug is a creature of the devil; like the scrunt will hide in the ground, the bug remains unseen; Mr. Heap emphasises that the bug too is “very hairy”; and brooms and other household items brandished by Mr. Heep and the Mexican women will reappear in the climactic scenes where all six of them use them as protection against the scrunt. Additionally, the idea of a devil-creature foreshadows the bedtime story itself, in many ways: both are ancient beliefs, both are translated from another language (Spanish, Korean) for Mr. Heep’s benefit, through a parent-child relationship (from the Mexican daughters by their father, from the Korean mother by her daughter).

The importance of having context

A lot of what may seem risible and strange about this film fall into place when the full context of the narrative is known. An issue that seems to have posed a particular problem is the appearance and personality of Story, the sea nymph – like the introduction of the dinosaurs in Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011), she becomes the final straw that destroys the film for people already uncomfortable with it. I agree, even after all the times I have watched this film, that in early scenes Bryce Dallas Howard is not really otherworldly enough to be entirely convincing as a being from a spiritual world. In later scenes, however, for example in a weakened state in the shower in Vick Ran’s apartment, she is much more convincingly ethereal, and as the “born-again” Madam Narf at the end she is very determined and imposing.

Initially I had several issues with the early sequence between Story and Mr. Heep in his house, when he wakes up after she has saved him from drowning in the pool. The atmosphere is so awkward, strange, and slow with all the pauses, that during the first viewing I started to cringe, like – possibly – many of my fellow audience members. With a greater insight into the characters, and what is at stake for them, however, these scenes actually seem fine. The strangeness mainly springs from a change in Mr. Heep’s behaviour. After discovering that the presence of Story has caused him to stop stuttering, he is speaking slowly and methodically as if now unfamiliar with his voice. Furthermore, this is the only situation in the film where he is not using his glasses. Not seldom in films glasses on/off signals a change in personality. Traditionally, perhaps, glasses mean clear-sightedness, but here more of a protective shield – without them he is a much more vulnerable and depressed person.

Later we will learn that, like so many Shyamalan characters, he has retreated from the world as a consequence of horrific violence: his wife and children were killed by a criminal breaking into his home (echoing The Village and more specifically Unbreakable). The full extent of the way this is blighting his current existence can be pieced together by subtle clues. In a poetic early scene, with an air of a nightly ritual, through a window we follow him inside his house after a long, weary day, and we can see, but just barely, that he is handling a book. The next day, Story finds this diary – attracted to shiny things, she is drawn to it by its metal lock – and learns the secret of his past. “Your thoughts are very sad. Most are of one night,” Story says. Considering how thick the diary is, we can only guess at how incessantly his mind must be circling the disaster. So we should not be surprised that the sudden presence in his home – where he probably does not have many visitors in the first place – of a young girl that may remind him of his wife or daughters, causes his current air of utter lifelessness and resignation.

More context: when he resuscitates Story late in the film by drawing upon his grief for his family, he exclaims, “I’ll miss your faces. Oh, they remind me of God.” This could be a specific reason for why the camera stops looking at him through the window in the early scene, and slowly tilts up to look into the heavens – reading about his family reminds him of God. Furthermore, the resonance of this idea may then bleed back to colour how we experience the resuscitation scene – this seemingly banal situation may now appear less so. (Of course, that specific reason for the camera movement comes in addition to a number of general reasons: for the poetry and grace of the movement itself, for general atmosphere, for foreshadowing the coming of the mythical great eagle, for possibly indicating that he will soon nod off to sleep – we see him wake up later.)

Context is also important for the emergence of ironic humour – in contrast to the often broadly farcical elements – that on repeated viewings ultimately appears to permeate large portions of the film. For example, the tenants of the building seem very attached to their apartments – one of them even at one point presents himself as “I’m 13B”, and the Korean family have their apartment number on an inside wall – as if living in their own private worlds. When Story says she comes from The Blue World, Mr. Heep almost obsessively asks, “Is that an apartment?” Story lives in some sort of cave underneath the swimming pool, but thinking about it precisely as an apartment instead will open up possibilities. In one scene Mr. Heep swims down to the cave to get some magic mud to save Story’s life, but he seems doomed to drown when the door handle breaks, trapping him inside. Seen from the apartment angle, however, this dramatic mishap is amusingly just another manifestation of all the prosaic breakdowns he is seen to have to deal with throughout the film. Later, when he hides the mud from the Korean girl, pretending that the object has to do with “apartment business”, on an ironic level this is then not really a lie. Shyamalan seems to have taken care to build small details like this into the film, serving one obvious function, but also emitting secondary signals that only become apparent on repeat viewings. One evening, there is a message on Mr. Heep’s receiver: “I smell something awful coming from the upstairs apartment. I think someone may have died and the body is decomposing. I know I said this last week, but…” The bit player actress Nell Johnson‘s wonderfully plaintive voice perfectly illustrates the kind of kooks Mr. Heep has to deal with on a regular basis, but the fact that she has first presented herself as Betty Pen amusingly connects to the big search for a writer among the tenants he is doing the next morning.

Mixing the mundane and the monumental

Let us go back to the bug-killing scene for a moment. It takes almost one and a half minute and seems quite long for its meagre narrative content. But the long duration could be to let us really dig into the aggression and pride that Mr. Heep displays during the kill, in ironic contrast to the thoroughly down-trodden, little-respected figure he soon turns out to be. It is almost as if this scene is some kind of fantasy, where he is allowed to play the role of heroic Protector, and afterwards bask in the unconditional worship from people that would be completely helpless without him. This brings us to another reason for the long duration, namely to give this mundane bug-killing task a paradoxically epic proportion. This mixing of the mundane and the monumental is one of the most important characteristics of Lady in the Water, on many levels.

This is a film where a mythical sea nymph turns up in a swimming pool, and even more mundanely, the apartment building to which it is connected is not exactly fashionable. It is a film where five good-for-nothing slackers end up helping the nymph fly away on a giant eagle to a higher plane of existence. Where a book that will change the world is called “The Cookbook”. Where a woman fixing her make-up is in reality a sentinel watching out for monsters. Where the genre of romantic comedy is up for discussion moments after a narrow escape from a murderous demon-creature. Where the same creature suddenly starts to behave like a dog when confronted with a locked door. Where a character who is foretold of his future assassination is soon revealed to have received this news sitting on a toilet bowl.

For the contrasting effect of mundaneness is also built into such little details: Simultaneous with the big revelation that Vick Ran is the writer that Mr. Heep has been frantically looking for, his sister reprimands Vick, “That is not how you fold” (the siblings have just finished washing their clothes). In fact, Vick’s sister is a constant source of such mundaneness. When Vick has received the news of his future death, the situation is soon interrupted by her waltzing in, as she implies that Vick has been asking the sea nymph banal questions about how many children he is going to get. Upon another big revelation, that Vick’s book is destined to change the world, his incredulous sister gratingly interrupts “The Cookbook??”

Furthermore, the grandness of film’s fantasy components is constantly undermined by absurd and/or farcical humour: Large portions of the bedtime story are told through the Korean girl’s intense, guttural and strangely accented voice, with a rather uncertain grammatical precision. When the sea nymph is laying in a coma, possibly dead, the day is saved by the aforementioned little boy who can read signs from the universe out of the drawings on cereal boxes. After having been resurrected, the nymph is guarded on her way to safety by the Guild, using brooms and rolling pins as weapons. Even in the serious scene where Vick first meets the nymph and is spiritually awakened by her presence, the solemnity of the moment is gently undercut by Mr. Heep asking him, almost teasingly, “Is it a pins-and-needles kind of feeling?” (The nymph has told Mr. Heep that an awakening will be marked by such a sensation.) The jewel in the crown is, of course, how the high-blown dramatics of the climax suddenly lurches into comedy, when it is revealed that it is the idiot Reggie who is The Guardian, destined to save everyone. (Shyamalan emphasises that Reggie even gets to observe the Tartutic, a unique opportunity since “no one who has seen them has lived”).

Mixing gravity and levity

Lady in the Water begs the question: how serious is all this – is any of it serious? I have no doubt that Shyamalan really believes in the basic New Age-like message of finding one’s purpose, spiritual awakening and the interconnectivity of all beings and actions. Furthermore, almost everything in the scenes where Mr. Heep is alone with the sea nymph is serious – islands of solid gravity in a film with so many comedic elements. That gravity and comedy can exist side by side is nothing new and should not really pose a problem – even in a film like The Princess Bride (Rob Reiner, 1987), which is almost in its entirety a knowing send-up of fantasy tropes, we are still meant to believe in the central love relationship.

So Shyamalan is clearly serious on quite a few levels, but also at the same time very aware of the inherent absurdity of the concept. The four “wildest” scenes of the film are the ones with Mr. Heep pretending to be a child, the children’s game prying secrets out of the nymph, Mr. Dury in the bathroom reading signs from his crossword puzzle, his son reading signs from cereal boxes. The first three appear in quite rapid succession in the middle of the film and their playfulness reminds me of the central section of Sonatine (Takeshi Kitano, 1993), where the gangsters take a long break from the plot to fool around on the beach. In these wild scenes Shyamalan is serious about their expression of the film’s over-arching themes and their importance as stepping stones towards a serious conclusion of the film. Their execution, however, relentlessly reeks of undercutting irony.

This leads us to one of the most mystifying things about Lady in the Water, namely the apparent lack of consensus whether its humour is unintentional or not, or even whether there is any attempt at all. A number of critics who hated the film have told me, “The only humour in the film was involuntary!” I have shied away from revisiting old reviews when writing this, but as I recall, it was common to take most of the many humorous elements I detail in this article, as sheer idiocy rather than attempts at humour. As experienced a critic as Philip French in the Observer claims that, “this pretentious, humourless (except for a joke-about-a-joke centring on the film critic) movie is breathtaking in its absurdity.” One thing is to acknowledge attempts at humour and decide that they fall flat, but this is really weird. (At least it is sweet, in a kind of twisted self-centred way, that the film critic only understood the humour about the film critic.) I hate to quote this other review, by Richard Scheib, for it is quite favourable to the film, but it handily demonstrates the attitude:

“There are certainly times that Lady in the Water teeters on the edge of the completely loopy. There is the moment where one of the characters expostulates aloud: “He’s hearing the voice of God through a crossword puzzle!” [quote corrected by me] and the very mentioning of such tends to emphasize the absurdity that had been bubbling beneath the scene (and sends the audience off into unintentional titters). Later when we get to another character searching for clues as to what is going on in a shelf of cereal boxes, Shyamalan seems to be defying the audience to start laughing. One suspects that underneath it all Shyamalan is a loopy mystic who believes in signs, portents and predestination himself.”

Here the idea of unintentionality comes up again. The absurdity has in fact been bubbling, quite freely, through a lot of the film already. We are meant to laugh openly about the uncritical adulation that the expostulating lady directs towards Mr. Dury’s reluctant prophet. The above two scenes would have been written, acted and staged totally different if they were not meant to be drenched in absurdity. For example, just see Giamatti’s mischievous acting as he persuades Mr. Dury to give interpreting a whirl; how one of the smokers is making grimaces in the background; how everyone is strangely crowded into the very small bathroom; how they act like children, either squeeze together to look over the shoulders at the crossword puzzle or gawking at Story; the mock-solemn drums on the soundtrack when Mr. Dury starts interpreting. In the signs-from-the-cereal-box scene, there is the studiously toneless voice of the boy; how everyone yet again is obsessively gathered around to watch; how one of the smokers is holding up his finger in a strangely stylised way; how all the smokers are their usual one-note slacker selves; how Mr. Dury is constantly shushed down for disturbing the proceedings because he cannot help praising his son – and the boy is actually reading signs from the universe on a cereal box!

What is really strange is how it apparently goes unnoticed that Paul Giamatti has created a wonderful comic character in Mr. Heep, with endlessly inventive detail. Just watch his body language in the various scenes when he tries to ingratiate himself with the Korean mother, or when he suddenly sits up in a fixed position, as if he were just doing gymnastics when the film critic discovers him laying on the ground after having escaped the demon-creature. Furthermore, Jeffrey Wright hits the tone perfectly as Mr. Dury, subtly caricaturing his eloquence and air of aloof analytical prowess. The way his love of words causes him to let them melt on his tongue is exquisite, ditto his studiously soft and learned voice, always searching for the most precise and elegant wording (“Joey, Mr. Heep appears disquieted”). Shyamalan clearly relishes creating a character that is a sly inversion of the typical black stereotype of being folksy and down-to-earth.

While the film critic Mr. Farber’s genre-reflexive encounter with the creature is a bit old hat after Scream (Wes Craven, 1996), Bob Balaban nails with ghoulish precision the caricature of the impossibly jaded, seen-it-all and pompously self-important critic who has long lost any pleasure from watching movies. His self-pitying performance of lines like, “There is no originality left in the world, Mr. Heep,” and (about a romance movie), “Characters were walking around saying their thoughts out loud,” perfectly captures his pain of being exposed to such contemptible material as cinema.

While on the subject of characters, let us talk a bit about Shyamalan himself. Lady in the Water is a foolhardy project on so many levels: following a critically drubbed work as The Village with an even more difficult and risky concept; then baiting that same critical community with the loathsome Mr. Farber; and not least, to cast himself as a writer of a book that is destined to change the world. That last item seemed a central factor in making several reviewers go almost berserk with rage. It is a strange phenomenon, a plot element almost worthy of the film itself, that such a sweet and childlike film as Lady in the Water should inspire such hateful reviews. (Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian calling him an “idiot” is certainly a low point in recent film criticism.)

Casting himself in such a role was supposedly self-aggrandizement on a galactic scale. Nobody complained, however, when he in his three previous films cast himself as an unlikable and arrogant security guard, a reptilian drug dealer, and a guy who caused the death of his neighbour’s wife. Shyamalan has an interesting face, but lacks expressive range and is not a great actor. Still he manages to project the earnestness and ordinariness – he is about the only non-quirky character in the building – that the role requires. On an acting level it is hard to see his turn as disastrous, and on the aggrandizement level the character’s humility is constantly emphasised. Is Shyamalan not simply embodying every writer’s dream to somehow change the world? Other than that, Lady in the Water was an intensely personal work for him, so it is not that strange that he should want to play the part of another, similarly driven writer. In hindsight, his very earnest performance takes on a slightly tragic dimension, considering the film’s disastrous reception and the later decline of his career, both in artistic control and merit. Anyway, his presence in the film is quite well justified because it adds complexity to the film’s important theme of self-reflexivity, the subject of the second article.

Childlike innocence

When approaching Lady in the Water it is all-important not to let go of the notion that in many respects this is a children’s film. Since children or childlike beings have been central to the previous four films, this should not require that big an adjustment. Even a horror moment such as Mr. Heep and Story running away when the scrunt comes after them for the first time, is rooted in a child’s world – their uncontrollable panic should be recognisable for anyone who was ever afraid of the dark as a child, running away from unspeakable things in the shadows right behind us.

At the film’s core – never to be forgotten! – is a naivistic bedtime story, growing out of a tale that Shyamalan made up for his (at that time) two daughters. The names of this bedtime story’s beings, for example “narf” and “scrunt”, have been objects of derision, but this appears to be a highly irrelevant criticism – aren’t these just the kind of cutesy names one tends to use in stories for very small children? (The name “Tartutic”, however, is a wonderful phonetic concoction, and becomes very funny when introduced in the Korean girl’s intense and guttural voice.)

The cobbled-together feel of the bedtime story gradually revealed in Lady in the Water reflects the nature of the telling of such a story in real life. The constant addition of new material, the sudden expansion of its universe, an ever-widening number of rules and restrictions – all this is revealed, as will be detailed in Appendix 1, in the film in ten separate stages. Each stage can be said to correspond to each night in real life when your children are demanding a continuation of the bedtime story – or maybe to one response to a child’s curious question during one of those nightly sessions. All the time you are making it up as you go along, and later you are stuck with the result of your improvisations and just have to go on building on them. The way the story of Lady in the Water seems to sort of lumber along, lurching back and forth, appears to have infuriated many, but seen in this context this should be less of a problem. (This portioning-out also creates a humorous effect since the beleaguered Mr. Heep has to cope with constantly new and ever-more-complex information.)

So Lady in the Water is a children’s film with adult characters, but central to the film is that these compromised adults have to become like children again. In the course of the film, virtually every adult character comes to believe in the bedtime story as real. One of the theme’s most subtle manifestations is found in the end credits music, which is finalised with “The Times They Are a’Changin’”, performed by A Whisper in the Noise. Towards the end of the song the vocals are joined by children’s voices, as if an adult is being transformed into a child, and in the song’s very last chorus the children sing alone, as if the transformation is now complete. (Seconds later a text dedicates the film to Shyamalan’s small daughters.)

To follow the music’s connection to the children theme a bit further: the very first sound we hear in the film is a boys’ choir, in the first bars of James Newton Howard‘s score. (Furthermore, it is immediately followed by the childlike tones of a music box.) So both the first and last sounds of the film are made by children, and since they respectively come from a boys’ choir and a girls’ choir, both sexes are covered – in typical Shyamalan methodical fashion. The haunting boys’ choir theme, where soprano voices undulate back and forth in quasi-religious fashion, reappears three times in the film. First, when the childlike Story becomes frightened by the scrunt’s presence outside Mr. Heep’s house. Second, when the Korean girl informs Mr. Heep that, “…my mother thinks of you as stranger. You have to make her see you as a child, innocent. Then she will tell you the bedtime story.” Especially this second occurrence is strongly tied to childlikeness, but the third time comes when the characters are in utmost despair, furthest away from childlikeness, after Mr. Heep have confronted the scrunt only to discover he is not the Guardian after all. (The hushed tone of the dialogue, “I cannot protect you. Where are the Tartutic? Why isn’t he being punished? Where is the justice?” together with Howard’s music provides one of the most poetic moments of the film.) It is notable that the boys’ choir theme is quite similar to a theme from Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), the reference justified by the fact that both works deal with the recreation in real life of a myth, in Spielberg that of a children’s novel (“Pinocchio”). Another link is that A.I. features Haley Joel Osment, whom Shyamalan gave his breakthrough in The Sixth Sense.

The theme of childlikeness/adults returning to childhood permeates the film in many other ways. The animated prologue can be seen as a short children’s film laying out the background for Story’s emergence from The Blue World into the world of Man. Its first shot seems to portray an adult sea nymph and a man, each with a child. Story is portrayed as childlike and innocent throughout, although in an ironic inversion of the other characters’ trajectory, after having been resuscitated towards the end of the film she has evolved into a much more mature being, the Madam Narf. The little son of the crossword expert Mr. Dury talks like an adult, thus seemingly also going against the pattern of the film, but when he finally interprets the signs from the universe, they originate from the childish cartoons on cereal boxes. Vick Ran and his sister are constantly involved in childish pretend-fights. Even the age of Vick Ran until his future assassination is measured in children (“Your sister will have seven children. You will see the first two”). In addition to being sisters, all of the people finally found to constitute the Guild are specifically marked as children (the five Mexican daughters, the Korean girl and Vick Ran’s sister, the latter by mentioning her mother, twice).

The most childlike situation of the entire film is of course the scene we have mentioned several times already, where Mr. Heep has to pretend to be a child to ingratiate himself with the Korean girl’s incredibly hostile mother. This is in fact just the culmination of Mr. Heep’s constant, but pathetically futile attempts at ingratiation earlier in the film. The vast array of gestures of a more grown-up nature he has earlier employed, however, is here substituted with a stylised, exaggerated version of a child’s behaviour. Guided by the Korean girl – who, in line with the theme, is actually named Young-Soon – he is putting on a show, play-acting to be a child, with a “moustache” of milk. The charade is horrendously transparent, but paradoxically it still works, so Mr. Heep gets to know a large chunk of the bedtime story.

Discovering his inner child seems to result in a triumphant breakthrough, for in the next scene Mr. Heep is suddenly exuberant and energised. His enthusiasm infects the others in what turns out to be the film’s best scene, where Vick’s sister is selected as an interpreter to relay Story’s signs as the latter indirectly answers Mr. Heep’s questions. The gossipy sister, who so far has often been an irritating character, suddenly finds her purpose and appears as sweet and charming. She speaks to Story as if she was a teacher at primary school, but at the same time she eagerly throws herself into a guessing game she remembers from her own childhood. The game shall enable Story, who is not supposed to tell anyone much about The Blue World, to give out information without not really telling. (We will return to discuss this scene and its stylised mise-en-scène in the second article.)

Soon after, another brilliantly playful scene follows, where a bunch of characters from the apartment building are playing out some sort of “party game” in front of a bemused Story, who looks like a child who only half-understands the game that the grown-ups are playing. Even though the game is serious to Mr. Heep, Mr. Dury, who very reluctantly plays the role of the Interpreter foretold in the bedtime story, clings to the idea that it is just a game (“We’re just playing here, right?”).

Shyamalan’s previous four films – except to a certain degree Signs – have all been providing an extremely bleak view of a dysfunctional world, filled to the brim with unspeakable crimes and horrendous murders, to such an extent that all that decent people can do is to seal themselves off from it. After all this, it seems that Shyamalan has felt an urge to become a child again himself, with this new type of material. He is reminiscent of Mr. Leeds, the hermit character who is always confined to his apartment, with its lamps burning even in daytime as if he has shuttered the windows to keep any light from coming in, while obsessively watching TV footage from the Iraq War. In a film that for me has never really packed that much emotional punch, right from the first viewing there has been one exceptionally moving moment. Here Mr. Leeds, finally lured out of his apartment, suddenly reveals his anguished emotions, in the most tormented voice imaginable: “I wanted to believe more than most. I wanna be like a child again. I needed to believe there’s more than this awfulness around us…”. Judging from the voices on his TV just before, this night that Story is laying seemingly lifeless and all hope appears to have been lost, it is the very same night that the bombing of Baghdad has started.

The Iraq War connects to the depictions of war in the prologue – and could be the concrete reason for the emergence of the sea nymph at this exact time – but also links Mr. Leeds and Mr. Heep, from the outset the film’s least childlike characters (except for the film critic). Mr. Leeds specifically warns Mr. Heep not to become like him, and they are the ones who have withdrawn the most, Mr. Leeds to his apartment, Mr. Heep to his house – from the world but also from the others in the building. (In another of the film’s many silly counterpoints, Mr. Bubchik is even more physically withdrawn, but to his bathroom). While the other apartments are constantly soothed by a wide variety of easy-listening music – as if in denial of the various wars and desperate circumstances of the world – these two are surrounded by violence: Mr. Leeds transfixed by TV war reports, Mr. Heep’s TV blanketed by similar reports on the night he meets Story. One report is about church services for soldiers before going to war, but in contrast to that of The Blue World, this kind of spirituality serves the war machine, the commentator announcing that “chaplains rallied the troops”. It also seems significant that Mr. Heep is awakened from his slumber by the TV sound of cannon fire – the war is the direct reason for him being up at the right time to discover Story.

Low points and high points

Let us close off by first pointing out some items that in my view still do not work in the film and later some of its highlights. It is hard to disagree on the most basic level with the notions that Shyamalan is championing in Lady in the Water: finding one’s purpose, spiritual awakening and the interconnectivity of everything. But he does not succeed, even from a point of departure of intended simplicity, in ultimately making them transcend the banal. In my view, the common accusation against the film of pretentiousness is a mistake – it fails to take into account its abundant playfulness and naivistic nature of its myth – but at the same time, Shyamalan still seems to work towards an ending that attempts to influence audiences on a deeper spiritual level.

This ties in with my biggest single misgiving: not on any of my many repeat viewings have I been able to feel much during the late scene where Mr. Heep, by pouring out all his pent-up grief, is able to resuscitate and complete the sea nymph. The situation and dialogue are meant to be very basic, raw and sincere, but somehow what is supposed to be the most emotional and serious moment of the film is for me essentially stillborn. (The link to the camera movement towards the heavens already pointed out in the “context” chapter provides some emotion though.) Furthermore, the use of the flamboyant and eccentric cinematographer Christopher Doyle was a deliberate choice by Shyamalan to visually “loosen up” a bit. Although, as Bordwell points out, it has resulted in some untraditional solutions, I find myself missing the extreme visual precision and authority, Shyamalan’s perhaps greatest strength, of the previous films. To some extent, in comparison Lady in the Water seems less visually rich and meaningful – but on the other hand, employing the old-style Shyamalan regimen might not have suited this more diverse, sprawling material.

There are also technical issues. Quite a few of the goofs listed at the IMDb are not mistakes on closer inspection, but the gravest continuity problems go unmentioned, namely the physical appearance of Mr. Heep’s house – in one shot there are suddenly no front doorsteps! – and also major inconsistencies in its geographical relation to the pool and the rest of the backyard. There are also some minor issues. Some intermittent, brief shots of the backyard with the characters talking in voice-over have the air of being explanatory dialogue inserted during the protracted re-editing process, to address test audiences’ problems following the plot, but the shots nevertheless work as mood. What seems to be an establishing shot of Mr. Heep’s house before he decides to go to try out his Guardian powers against the scrunt, is directly misleading, however, because at that point the characters are staying inside Vick Ran’s apartment. Late in the film, where the other characters are gone and Vick Ran and his sister stay behind to guard the sea nymph’s comatose body, there are two rather strange shots when Vick Ran seems to sense something and leaves to investigate, but the situation just runs awkwardly out in the sand.

The climax, with the final stand-off with the scrunt and the appearance of the Tartutic and the giant eagle, is clearly intended as awe-inspiring and spiritually uplifting. It has never really worked for me on that level – although Howard’s magnificently dramatic music is certainly striving to help – but on repeated viewings, like the prologue, it has quietly grown. A good example of how becoming consciously aware of context and style can create emotion and resonance in a situation originally felt to be barren, the stylised approach to mise-en-scène and camera placement becomes very inspiring. And the film’s quietly bitter-sweet closing seconds are subtle and very moving. I will return to the ending in the second article.

Lady in the Water contains several occasions of brilliance. The shot where the scrunt attacks the sea nymph by suddenly breaking through a window is a quintessential horror moment, strengthened by the inventive decision to leave the monster out of focus. This suggests metaphor, that it represents a half-shapeless embodiment of some primal fear inside her. The blind panic that grips the characters running away during the first scrunt attack, described in the previous chapter, is another form of stylisation of the basically same primal fear (to be further discussed in the second article).

The scene with Mr. Heep on his nightly challenge of the scrunt, with the nymph “directing” him by walkie-talkie, shows expert handling of tension-building. The fact that the scrunt can hide in the ground and blend in with the grass is in itself quite a delightful idea. But here this turns into pure magic, in the moment when it cannot help give itself away when looked at through a mirror. The image of a single big red eye staring out of a sea of grass is something that could have been imagined by a child but at the same time it is very threatening in a basic, existential way. The scrunt’s appearance thereafter in all its sinister might is also very well handled.

The dissonant atmosphere during the party scene, where the world’s signs are definitely not lining up favourably, is also masterfully constructed, full of small unsettling details. The film’s self-reflexivity, original and complex, will be discussed in the second article. Other than that, we have already talked about the playfully absurd comedy of its central section. Like Mr. Heep gets a shot in the arm by discovering his inner child, from this point Lady in the Water really starts firing on all cylinders. However many times I see it, for the rest of the film I feel energised and inspired, as one always feels watching a really good film.

Anyway, a large number of people just seem locked out of the film, the exact opposite of what Shyamalan wanted. I can only encourage you to watch it again. There are many precedents in film history for savagely slaughtered works to appear in a better light with the perspective of time. M. Night Shyamalan has made a very demanding film, not only with a bewildering array of tonality shifts, but also an abundant mix of genres and approaches: children’s film, horror, fantasy, farce, absurd comedy, ironic self-reflexivity, coming-of-age, spiritual journey, New Age. Lady in the Water consists of many elements that on their own are not particularly original, but as befits a film about transformative power, as a whole it is original.

*

Appendix 1: Pop culture and fantasy role-playing games

In Richard Scheib’s review he suggests that, “There is the sense, something we also saw in Unbreakable, that fictional stories like comic books and fairytales (sic) have a deeper underlying truth and that people need to discover what archetypes it is their purpose to play out.” Joseph Campbell is an American mythologist whose investigation of common archetypes and structure of ancient mythologies has been highly influential, not least in popular culture, for example in George Lucas’ Star Wars concept. Campbell delineated a basic pattern called a monomyth, which is summed up in his famous 1949 work, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces”, as “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.” In this interview about the film, Paul Giamatti suggests that, “There’s a lot of Joseph Campbell stuff. I mean, I don’t know whether he [Shyamalan] intends that, or he’s consciously doing that, but there’s an awful lot of it in there.” The Campbell angle is picked up in this defence of Lady in the Water, which by the way is a good example of someone going totally overboard in his estimation of the film’s importance: “The problem is that this film was ahead of its time. It bombed in the box office and memetically it failed – because we weren’t ready for it yet. It’s a lot like reading the story of Oedipus to a three year old.” Campbell with his exploration of mythology and perhaps also Vladimir Propp with his analysis of basic elements of fairy tales (from Russia) could certainly be a promising avenue for the further understanding of Lady in the Water.

In this appendix, however, I shall concentrate on popular culture. Bordwell in his foreword to “The Man Who Heard Voices” has been among those who have pointed out that Shyamalan’s previous four films all had contained a subtext/discussion of various pop cultural genres or phenomena – low-cultural forms generally held in little regard. In The Sixth Sense it was ghost stories; in Unbreakable superhero comics; in Signs the urban myth of alien-made crop circles and the science fiction sub-genre of alien invasion; in The Village horror movies.

Nina Jacobson, a powerful Disney executive, was a Shyamalan champion right from The Sixth Sense, but their relationship gradually turned sour, especially with the advent of The Village. Her strong misgivings about the script for Lady in the Water made Shyamalan leave Disney for Warner, and one of her many complaints, as detailed by Bamberger, was why there were so many rules. She probably referred to the more and more intricate ceremonies and restrictions the characters must observe. With her intimate knowledge of Shyamalan’s films and their pop culture subtext, however, it is strange that she could not at least form a theory about why all the rules were there.

In Lady in the Water, the pop cultural connection is obviously fantasy literature, but more specifically fantasy role-playing games, à la Dungeons & Dragons. At the very least, it seems a useful way for us to organise the bewildering plot. In such games one can, after various accomplishments, proceed to new levels. In Lady in the Water this corresponds to the (roughly) ten stages in which new information about The Blue World and the bedtime story is given out. When a new level is reached in such games, one often goes on a quest – in the schema below not always, and the quest is of a more limited nature dictated by geographical restrictions – to accomplish something that will give access to the next level. On the way one may pick up objects that will turn out to be useful on later levels. For example, note how the Mexican daughters in the opening scene all carry objects that will be useful as weapons towards the end of the film. On a quest, one may also attain new powers and abilities. The way that the seemingly ordinary – although very, very quirky! – people in the apartment building turn out to be embodiments of archetypes from a typical fantasy setting seems to be another link to role-playing games. Thus, in Lady in the Water we encounter the following generic “secret identities”: The Healer, The Guardian, The Guild, The Symbolist/Interpreter (“They have weird names!”). Later, Shyamalan adds some of his own: “one whose opinion is highly respected” and The Man Who Has No Secrets – the latter with typical Shyamalan whimsy, and delightfully literal-minded in this case, for the reason that Mr. Bubchik lives up to that identity is that his wife cannot stop blurting out his “secrets” of unsavoury bodily imperfections. Even Story herself has a “secret identity”, the Madam Narf, a leader among her people.

The ten stages of Lady in the Water can be defined as follows:

- (1) An unknown voice-over tells the background of the whole myth, and following a set-up of the apartment building environment, the story starts in earnest when Mr. Heep meets Story – this starts him out on a quest to find out about the bedtime story

- (2) The Korean mother tells Mr. Heep the basics about narfs and their mission and how afterwards a great eagle will transport them away

- (3) Story tells Mr. Heep that she is to meet a writer – this starts him out on a quest to find the writer

- (4) The Korean girl tells Mr. Heep about scrunts, ferocious creatures that aim to kill any narf out of the water

- (5) The Korean mother tells Mr. Heep about the Tartutic, “the lawkeepers of this bedtime story”, and how to find some mud called Kii to heal Story, who has been attacked by a scrunt – this starts him out on a quest to find the Kii

- (6) The Korean girl tells Mr. Heep that Story may not be just any narf, but Madam Narf herself, and also to get the rest of the bedtime story out of her mother, Mr. Heep must make her stop seeing him as a stranger – this starts him out on a quest to ingratiate himself with the mother by pretending to be an innocent child

- (7) Mr. Heep is exploding with new information about various added characters of the story, about whom he gets some sort of confirmation from Story – this starts him out on a quest to find the identities of The Healer, The Symbolist/Interpreter and The Guild (Story thinks Mr. Heep himself is The Guardian)

- (8) The Interpreter, a very reluctant Mr. Dury, envisions a set-up to enable Story to be taken to safety by the giant eagle without getting killed by the scrunt, which is now breaking every rule to get at her because she is in fact about to become Madam Narf – this starts everyone out on a quest to organise a big party and later to use it as a smokescreen to smuggle Story away

- (9) While the party is being planned, Story decides to tell Mr. Heep how a human being can unearth the scrunt, allowing Mr. Heep, as the Guardian, to familiarise himself with the scrunt to better protect Story during the party – this starts him out on a quest to confront the scrunt

- (10) Most of the information in stage 8 turned out to be wrong. Story is in a coma after another scrunt attack. It turns out that The Interpreter is actually Mr. Dury’s son, who tells everyone vital information (“There is a ceremony to be done”) about various other secret magic identities among the tenants – this starts everyone out on a quest to find these people, bring everyone together to revive Story and make sure that she stays in one piece long enough to be transported away by the great eagle.

Appendix 2: Additional points

This appendix lists some additional points that do not naturally fit into the article but deserve to be mentioned.

- The frame grabs above are taken from the opening scene and the scene where Story is resuscitated. In the opening scene the colours of the five Mexican daughters’ clothes are quite varied, but in the later scene they all have clothes with pink/reddish colours, binding them together in a way that fits the scene’s spirit of collaborative effort. The five sisters turn out to be members of the seven-person Guild, together with the Korean girl and Vick Ran’s sister. Here medallions seem to be another binding object. All five Mexicans, except one, have medallions around their necks. The Korean girl also has one. Vick’s sister lacks a medallion but her brother has been wearing one throughout the film. It is also of note that Story stole a medallion from a pool chair when Mr. Heep spotted her for the first time.

- The seven members of The Guild are all supposed to be sisters. This seems to be reason for the inclusion of the Korean girl’s line, which could appear to be a throw-away line purely for comic relief, about her mother complaining that, “…why can’t I be like my older sister. She married a dentist.” This could also be an indication that she may come to marry Mr. Heep, a former doctor. Her disappointment in one scene that Mr. Heep does not come around to ask about the bedtime story any more, has a hint of longing and romantic attachment.

- Mr. Heep’s stutter seems to be due to post-traumatic stress, caused by the murder of his family. In one scene he is seen stuttering to himself, while “ordinary” stutterers usually only do it when around others.

- In the end it turns out that Mr. Heep is The Healer. There are a number of clues to this throughout the film. Story makes a signal indicating a book. Earlier, Mr. Heep returned a book to the Korean girl (incidentally, by the ancient historian Herodotus, connecting to the film’s theme of ancientness.) Story also signals that healing has to be learned and in that scene the Korean girl says, “Mr. Heep loves learning.” After having read his diary, Story has found out that he used to be a doctor. As a superintendent, he is fixing various problems in the apartment building, as if he is treating its “illnesses”. He also shows “healing” abilities when he is giving Story hope at a point when she has lost faith in herself.

- Mr. Heep is saved from drowning by sucking air from a glass with air trapped in it. This is actually physically possible and Paul Giamatti did it in camera, as described in this interview.

- This suspense scene is well staged. For one thing, note that we in fact are shown the glass with the air, as well as the pen beside it which Mr. Heep use to get at the air, in a separate shot already as he is swimming into the cave. This foreshadowing lends solidity to the scene, so that the glass with the air does not appear out of nowhere, as an artificially inserted trick just to save him.

- There is a faint air of neglect in the intellectually aloof Mr. Dury’s relationship with his son. This is indicated by the boy saying, “This picture on the cereal box is supposed to make you feel happy. I feel sad, like that time you forgot to pick me up at school.”.

- Mr. Dury is obsessed with crosswords in a way reminiscent of the theme of “obsessive thinking” in The Village. The high number of rules in Lady in the Water also remind one about the highly regulated community in The Village.

- When Reggie is distracted by the arrival of the eagle, losing control of the scrunt but saved by the Tartutic, he is looking at the eagle over the shoulder of the weaker part of his body.

- Many of the tenants have easy-listening music on in their apartments. The callous film critic paradoxically listens to “I’m getting sentimental over you” performed by the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra.

- As noted, many of the things listed as goofs at the IMDb are not really errors after all. Unmentioned there, but hard to swallow, is that Mr. Heep actually seems to be lying unconscious on the bed and later falling asleep on the sofa with Story, in clothes that should have been soaking wet from his almost-drowning.