Lady in the Water, Part II: Self-reflexivity and visual stylisation

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the second of two articles reappraising Lady in the Water. The first article is about the film in general, including its important theme of childlike innocence. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

It’s ambitious to make the main point to the movie the story. To literally make the action of the movie the unfolding of the plot, in two ways. The plot unfolds, because all anybody does in the movie is sit around and tell each other the plot. It’s a really weird thing to try to do.

– Paul Giamatti, interviewed by Darkhorizons.com.

M. Night Shyamalan‘s severely under-appreciated Lady in the Water (2006) is virtually obsessed with stories and storytelling. Aubrey Wanliss-Orlebar, in a conversation about Shyamalan in the Norwegian film periodical Z, issue no. 4/2007, pointed out that all his major films before and including Lady in the Water, like those of the Taviani brothers, are also about the fascination of narratives and stories. Like many of his recurring themes and motifs, this gets more pronounced in Lady in the Water, to the point that its female protagonist is simply named Story. The film entirely takes place in and around one building, where every apartment seems to tell its own little story. The tenants become aware of themselves as characters in a story and it also becomes vital to them to learn to analyse it properly. The bedtime story so central to the film is told or elaborated upon by a wide variety of characters, connecting storytelling to other major themes of collaboration and interconnectedness. The way new parts of the bedtime story are constantly injected into the film creates humour, artificiality and just plain weirdness.

This article will examine the film’s discussion of all this, in addition to the related issues of interpretation, film criticism, artificiality, play-acting, the self-reflexive layer of the director casting himself, and Shyamalan’s idea that the story of the film is a re-enactment of an ancient myth. The article ends with an examination of prominent examples of the film’s stylised visualisation, using frame grabs.

Since Lady in the Water represents the culmination of a series of works that can be regarded as one long film, I will from time to time connect it to the previous works. Please note that I will not spend much time explaining the plot. It should be possible to follow the argument by context, without intimate knowledge of the film. A useful plot summation, however, can be gleaned from Appendix 1 of the first article through its description of the film’s ten stages.

The story becomes real

There is some early dialogue in The Sixth Sense with peculiar wording. The hero has received a framed plaque in recognition of outstanding work as a child psychologist. His wife proudly reads the glowing citation, while he is making light of it all. The wife protests, but does not say, “It’s true,” or “I agree with them,” but instead, “I believe what they wrote is real.” The wording of course connects to that film’s themes of reality, illusion and denial, but the emphasis on something that has been written is also a harbinger of an idea that would grow into a prominent theme.

For Shyamalan seems fascinated by the notion that fantastic tales can come true, more specifically through being recreated in the real world. In Stuart Little (Rob Minkoff, 1999), a family film that he only co-wrote, there is another harbinger. For its newly adopted hero says: “In the orphanage, we used to tell fairy tales of finding our families and having a party like this…. So I just wanted to thank each of you. Because now I know fairy tales are real.” In The Village its leader says, “Your son has made our stories real,” after the mentally disturbed Noah has re-enacted the “farce” of the make-believe monsters of the woods. In Unbreakable superhero abilities and behaviour are transposed from the world of comic books to real life. Shyamalan is careful to link this to something buried in Man’s collective unconscious by having Elijah say: “I believe comics are our last link to an ancient way of passing on history. The Egyptians drew on walls. Countries all over the world still pass on knowledge through pictorial forms. I believe comics are a form of history that someone somewhere felt or experienced.” The ancientness connects to the similar property of the sea nymph myth in Lady in the Water and the “pictorial forms” links to the same film’s animated prologue, with its highly simplified visuals, as if they were animated hieroglyphs. There are also ancient-looking pictorial signs on the wall of the sea nymph’s “apartment” below the swimming pool.

In perhaps the most audacious of the many breaks with realism in Signs, the son of the family has acquired a book about alien invasions – curiously, written by “scientists who have been persecuted for their beliefs” – which seems to accurately predict virtually every move of the aliens. The “story” becomes true again. The way the boy consults this book at various points throughout the film appears to be an embryonic form of the device in Lady in the Water – where new portions of information about the myth and the Blue World are regularly revealed to the humans, in the ten stages suggested in appendix 1 of the first article. Another link between these two films worth mentioning while we are at it, is established when Story says, “…the world will line up and reveal we are on the right path – that the universe will give us signs.” The quote pertains to the situation when the characters are using a big party as a smokescreen to let Story be taken away by the giant eagle undetected by the murderous demon-creature called the scrunt. This sense of being part of a larger predestined puzzle resembles the climactic situation in Signs, where the hero suddenly understands the implications of his deceased wife’s last words, his son’s asthma and his little daughter’s aversion to water, in a moment where everything seems to line up in a favourable way.

(For completeness’ sake, we also ought to mention the 2010 film Devil, directed by John Erick Dowdle. Shyamalan produced and came up with the story for this nifty B-movie which is much better than Shyamalan’s own late work. Here the folk tale “The Devil’s Meeting” is re-enacted in real life, when a group of people get trapped in a stuck elevator with the Devil masquerading as one of them, intending to kill them off.)

In Lady in the Water it turns out that “mermaids”, in the form of a sea nymph called Story, are real. She has come to help humans find their real purpose, revisiting the theme that is so important to the two main characters of Unbreakable, but the project in Lady in the Water is much more ambitious and original. I shall now try to determine the extent of this originality by examining other films where fantasy genre or fairy tale characters have crossed over into the real world to spend the bulk of the film there. I will further consider whether the co-existence of fantasy and “real” characters is permanent or if it comes as a surprise to the real world; whether the fantasy characters spring from an existing myth known to humans or not; and whether there is any attempt to suggest that what goes in the real world is a reflection of the fantasy world. To get as complete a discussion as possible, I will consider later works than Lady in the Water, although they of course cannot retroactively challenge its originality.

First, there seem to be remarkably few films at all with this set-up. (If angels or demons could be counted as generic fantasy or fairy tale characters, the number would increase considerably.) To stretch the definition of fantasy/fairy tale characters a bit, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Robert Zemeckis, 1988) has cartoon characters existing side by side with humans, but this is a permanent situation with which humans are very well familiar. To consider the “non-familiar” films: In Enchanted (Kevin Lima, 2007) characters from a fairy tale kingdom cross over to our world, and return after “having learned valuable lessons” (in the words of the film critic in Lady). Interestingly, its themes connect to Lady: Its hero is weighed down by past tragedy, and when he tells the princess of his decision to keep his little daughter away from the wishful thinking of fairy tales, she retorts by insisting that “dreams do come true”. Splash (Ron Howard, 1984) features a similar set-up, but the subject of mermaids puts it much closer to Lady. Also this film links to Lady, but more curiously, for the daughter of the director of Splash plays the sea nymph in the later film.

But contrary to the above films, the myth in Lady in the Water, even though it is Shyamalan’s own invention, is a myth specifically known to human society in that film, surviving as a half-forgotten Korean bedtime story. (Mermaid legends are of course known to man, but the mermaid in Splash is not anchored in any larger myth.) So characters from known myths crossing over to our reality seems quite original, if one discounts characters from Asgard and Norse myth doing something similar in the Marvel films Thor (Kenneth Branagh, 2011) and The Avengers (Joss Whedon, 2012). Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) is interesting here, however – as the first article touched upon, even though he does not physically come from a mythical world, the robot boy of that film ends up re-enacting the fairy tale-like children’s novel “Pinocchio”.

In Lady in the Water Shyamalan also takes the interaction between myth and Man a few steps further. First, it turns out that sea nymphs can foretell the future (in the voice-over by the male “Storyteller” during the prologue): “Once, Man and those in the water were linked. They inspired us. They spoke of the future. Man listened and it became real.” Once again in Shyamalan, a fairy tale (Story’s “story”) becomes real. Second, as mentioned in the first article, certain human characters in Lady in the Water have hidden magical powers, which will enable them to re-enact important elements of the myth. Like what happened between the myth and ancient Man of the prologue, the myth again tells humans, now of the modern age, of future events. If the humans can succeed in re-enacting these events, the story has again become real. For example, the myth is hinting about which of the humans are The Interpreter. As the Interpreter, Mr. Dury reads signs from his crossword puzzle that, in a way, enables them to look into the future to set up a situation that will save Story. Saving Story, by the way, also means that they will “save the story” by making it come true. When it ultimately turns out that it is Mr. Dury’s son who actually is the Interpreter, the boy reads his own signs to look into the future to set up a special ceremony. What it boils down to is that what we call reality is somehow basically the same, or just a reflection of, what happens in the myth. (Paul Giamatti has in interviews talked about the difficulty of actors playing characters whose realness is uncertain.) An interesting parallel might be drawn to the 1975 science fiction novel The Deep by John Crowley where characters in a medieval setting think their world is real, while they are in fact just endlessly playing out a standard fantasy plot.

The only other film I can think of that does something similar as Lady in the Water is not fantasy, but horror. In New Nightmare (Wes Craven, 1994) the real-life Wes Craven writes a script about the fictional horror character Freddy Krueger, but it turns out that everything he is writing is coming true in the real world. Real-life actress Heather Langenkamp is approached to reprise her original role in a new A Nightmare on Elm Street film, to be shot from the script that Craven is writing. Early in the film she is plagued by threatening phone calls from someone who sounds exactly like Freddy, and later the fictional world of Craven’s script will literally invade her “real world”. In both Lady in the Water and New Nightmare the real world is invaded by the world of the myth – a myth that is known to mankind – and to such a degree that real life (I am simplifying matters) will become a re-enactment of the world of myth.

Interpretation

Interpretation is central to Lady in the Water, in many meanings of the word: adaptation, translation, divination and explaining the meaning of a work of art. A Whisper in the Noise‘s rendering of “The Times They Are a’Changin‘” during the end credits is an interpretation of the Dylan song, fundamentally the same thing but still thoroughly refashioned. The story that unfolds in Lady in the Water is to a large extent another rendering of the ancient bedtime story, and like the Dylan song, the original story is transformed into something almost unrecognisable.

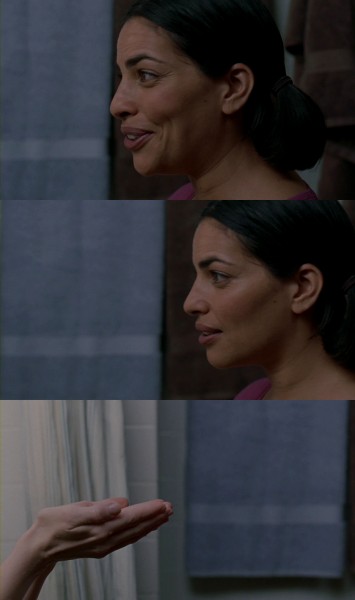

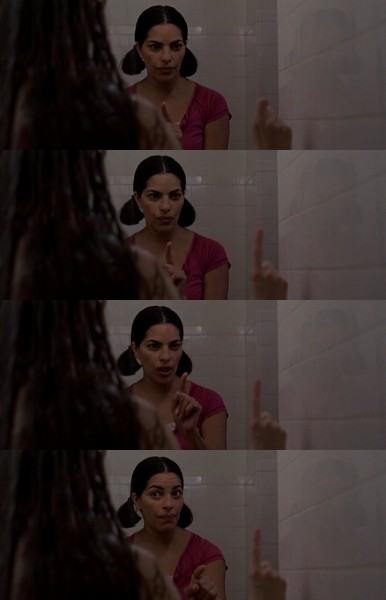

Translation occurs heavily in the film. The Mexican father translates his daughters’ claims that the bug of the opening scene is a creature of the devil, and the Korean girl translates her mother’s telling of the bedtime story. In the scene where Mr. Heep tries to get secrets out of Story through the children’s game, Vick Ran’s sister functions as an intermediary, rephrasing Mr. Heep’s questions and “translating” Story’s sign language into English. It is amusing, by the way, how Story, while sitting in the shower of Vick Ran’s apartment, appears in several scenes as some kind of oracle, with whom characters at regular intervals seek audience to consult her.

Now we come to the divination aspect. Interpretation is so important in Lady in the Water that even one of the magical persons is named The Interpreter. He is pivotal in one scene in the film’s central section, where everyone gathers around Story in the shower to figure out a way to smuggle her out of the building without her getting killed by the scrunt. Commanded to interpret by a triumphant and energised Mr. Heep, who almost wields the word “interpret” like a club, Mr. Dury is guessing away, trying his best to extract brilliant concepts from his crossword puzzle. The situation is indirectly reminiscent of how the hero of Signs had to interpret the meaning of his wife’s mysterious last words. For Mr. Dury, although at this point mistakenly believed to be The Interpreter, is “hearing the voice of God through a crossword puzzle,” in the awe-struck voice of Vick Ran’s sister. Given the very ordinary source for that voice and the religiousness of her outcry, this could actually be a concrete reference to how those seemingly banal words in Signs ultimately turned out to be divine wisdom.

Film criticism

The fourth and to us most important meaning of “interpret” is explaining the meaning of a work of art. In Unbreakable, Elijah’s mother gives the hero a crash course in how characters in comic books are drawn in order to foreshadow who is going to be the villain, and also what kind of villain. This will soon have a bearing on the story of Unbreakable itself. The presence of the film critic character, Mr. Farber, in Lady in the Water, serves as an enabler to open up a lot of similar self-reflective possibilities. Another all-important key to self-reflexivity is the fact that according to the bedtime story, all the characters with hidden magical powers in the apartment building “always appear in the story earlier.” This information in itself seems not that essential for the characters to hunt down the magical people, but rather intended to draw attention to Lady in the Water as a story, and, more specifically, to its extensive foreshadowing apparatus. This means that the characters now can disregard any ordinary tenant they meet in their daily life, and concentrate on those who explicitly have appeared in the film Lady in the Water (obviously only a fraction). So the characters must become aware of everyone, including themselves, as characters in a story, or else it would be meaningless for them to embrace that specific instruction of the bedtime story.

Through the ritual of the above-mentioned children’s game, they succeed in prying some clues out of Story as to who the magical people might be. On the sage advice of the film critic, an expert on plot structure and foreshadowing, Mr. Heep quickly rounds up the five smokers as The Guild, Mr. Dury as The Symbolist/Interpreter and Mrs. Bell as The Healer. (Mr. Heep believes himself to be The Guardian.) But all this turns out to be wrong, due to a combination of a lack of critical attitude towards the film critic’s advice and the critic’s own jaded sensibilities, which leads to a case of misdirection.

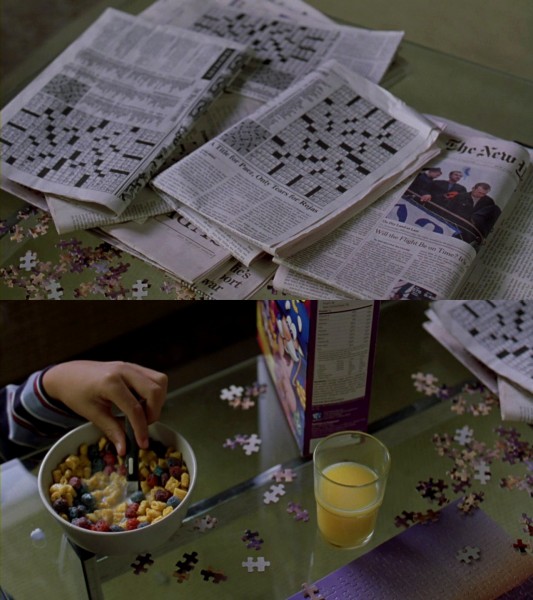

The critic’s advice for The Interpreter is basically sound: “Look for any character who is doing something mundane but required analysis. Someone who was skilled at puzzles.” The critic makes interpretation sound ridiculously easy, however. It is part and parcel of a critic’s work to project authority in reviews by sounding very sure about his/hers opinions. But Mr. Farber represents a type of critic who is unaware, or in convenient denial of, the complexities of the art form, and likes to impress people with superficial “knowledge”. Anyway, Mr. Heep thinks everything is easy and falls for Shyamalan’s misdirection. For Mr. Heep automatically goes for the obvious choice of Mr. Dury, but overlooks the fact that his little son seems as intelligent, as attached to his cereal (he even has it for lunch too) as his father to the crossword puzzle, and also overlooks the jigsaw puzzle, probably used by the son, on the table. There is also a very sly connection at play here: the many-coloured puzzle pieces are reminiscent of the many-coloured pieces of cereal in the son’s bowl, which connects his skill at puzzles directly to the cereal box, which will turn out to be his, as Mr. Heep puts it, “instrument specific to him to interpret.”

As for The Guild, things go seriously wrong for the critic. His “look for any group of characters that are always seen together” is of course fine, but then his boundless boredom with watching films gets the better of him. His disgusted outburst that they should also have “seemingly irrelevant and tedious dialogue that seems to regurgitate forever,” seems hardly essential for a guild. So Mr. Heep is led totally astray, and goes for the five stupid smokers and does not at all consider the five equally stupid Mexican daughters, although the latter seem much more “together” than the smokers, who are constantly quarrelling.

Mr. Heep’s newfound attitude that interpretation is easy also heavily influences the above-mentioned scene where Mr. Dury is pressed into the role as The Interpreter. Everyone takes everything he says at face value, as blinded by the authority of his role as Mr. Heep was by the film critic. So, faintly reminiscent of Life of Brian, Mr. Dury becomes, however unwillingly, a false prophet. When he tries to protest that “We’re all just seeing what we want to. I just made all that up,” no one wants to hear that he was basically guessing. His statement directly connects to the boy in The Sixth Sense, who said of the ghosts, “They only see what they wanna see.” The same kind of denial also afflicted the protagonist of that film, as well as the hero of Unbreakable, who basically had imprinted false memories in himself to keep up the denial of his real powers. In Lady in the Water the statement of course refers to the wave of enthusiasm that makes everybody lose all critical thinking. But it also introduces a variation of the interpretation theme, namely false interpretations. It is not uncommon that audiences, and also some critics I suspect, bring their own personal baggage to films in a way that interferes with the experience. Personal beliefs, political leanings, all kinds of hobby horses may turn the film into some kind of Rorschach test for the viewer’s likes and dislikes, raising objections deeply irrelevant to the film, making them unable to judge the film for what it is and attempts to do. Of course, Mr. Dury is not The Interpreter so his suggestions cannot be trusted anyway. On a thematic level, however, it is notable that he brings his own baggage to the interpretation, namely his obsession with crossword puzzles and his vivid experiences solving the specific one at hand.

It is tempting to connect this baggage angle to the hateful critical reception of Lady in the Water itself (outside of France). Many critics already perceived Shyamalan as a self-promoting director without much substance who had grown insufferably big-headed, and a large number also intensely disliked The Village, which was a very serious and solemn work. It is hard to believe that all this did not play some part, at least, in many critics’ insistence that Lady in the Water was fantastically pretentious and idiotically serious, making them unable to connect to its childlike playfulness. (This is discussed some more in the first article.)

The death of criticism and the birth of a people’s movement

At a point in the film when Story lies in a coma and everything looks very bleak, the film critic is killed off by the scrunt. Just before, the others have realised he is no good and Mr. Heep’s bitter, accusatory tone, now bereft of all illusion, is priceless when he says, “I asked someone. He acted like he knew.” The blunt cut to the death scene makes it look like a metaphorical punishment wished upon him by the others for putting Story’s life in jeopardy. It also has other meanings, of course, since as a representative of a wholly unimaginative, dysfunctional form of rationality, it is fitting that he is killed off by a creature he would otherwise deny the existence of.

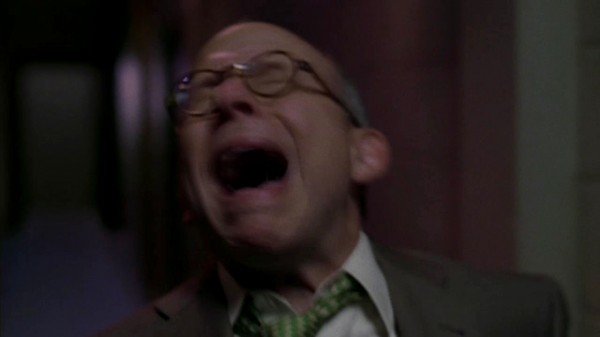

As for self-reflexivity, his realisation that the scene is like in a horror movie and his following genre-savvy reasoning is in itself rather old hat after Scream (Wes Craven, 1995). But his dialogue is very well written in its reflection of his incredibly dried-out, dispassionate attitude to what is supposed to be an art form: “It is precisely the moment where the mutation or beast will attempt to kill an unlikable side character. But in stories where there has been no prior cursing, nudity, killing or death such as in a family film, the unlikable character will narrowly escape his encounter and be referenced again later in the story having learned valuable lessons.” He continues, “He may even be given a humorous moment to allow the audience to feel good about him,” which turns out to be half-true, because he immediately breaks out in a ghoulishly power-crazy grin. This will be humorous to a viewer attuned to the film’s self-reflexivity, because he is in fact given a humorous moment – the humour, however, springs from the impossibility of feeling good about that smile, and also from the bizarrely short time from his prediction until the humorous moment occurs. Afterwards, before he is killed, he fantasises in megalomaniac fashion how he will run and shut the door, and the scrunt will land “a fraction of a second too late”.

His behaviour in this scene mirrors the other characters in interesting ways. Like the others, he is aware of himself as a character in a story. Like them, he is interpreting the story’s past scenes. Like The Interpreter, he is attempting to look into the story’s future. Like them – even though he has only appeared in a few scenes – he seems aware, on some level, of the entirety of the film, because he is quite correct that so far, Lady in the Water has fulfilled his criteria for a family film. His fatal error, however, is that he, in typical fashion for a simple-minded critic, has not grasped the complexity and especially the genre-blending nature of the film. It is also a horror film, so he can be killed. (On a parallel, more prosaic level: he is killed because at this point we are not sure whether Story is dead or just in a coma, so Shyamalan may use this incident to subconsciously increase our fear that Story is really dead.)

The exquisite irony here is that many real-life critics did not seem to get the genre-blending of Lady in the Water either. In some utterly bizarre way, life here imitated art. Shyamalan was so intent on killing this particular critic that he happened to make a film so difficult that the real-life critics could not understand it either. I am joking, but one could say that Shyamalan burned the whole house of Lady in the Water, to roast the pig, the film critic Mr. Farber, in it. [EDIT 21 Jan 2019: Amusingly, the critic is the film’s only casualty. This was pointed out by my Facebook friend Bruce Pullen, who followed up with “the critic never trusted the story until it bit him in the ass, literally; those who believed the story survived.“]

After Mr. Farber is killed, something very interesting happens to the other characters. We should first consider, however, why the film critic was included in Lady in the Water at all, and why he is such a nasty caricature. It is speculation, but not particularly far-fetched, to assume that it is as a reaction to the massive critical slaughter of The Village. Less so in The Sixth Sense perhaps, but in all the next four films, Shyamalan showed a desire to think outside the box, even within such a massively commercial format as films for the Disney conglomerate. It must have been a particularly bitter blow for him that critics insisted on judging such an artistically ambitious and wide-ranging film as The Village simply as a horror film, and found it extremely lacking (although, in my opinion, its few outright horror moments are magnificent). Shyamalan may have thought, why not do away with critics, because ordinary, non-jaded people can do a much better job? It is as if he suggests that regular people have the potential to surpass those above them in the cultural hierarchy – another manifestation, somehow, of his important theme of secret, hidden abilities. For what happens after Mr. Farber has been killed? There is a straight cut, seemingly pregnant with meaning, back again to the other characters. They stand over Story’s body, still comatose because the current incarnation of The Guild and The Interpreter have not been able to deliver the goods, to resuscitate her. But now, with the critic gone, a fog seems to have lifted. With a new sense of purpose and clarity of vision, these ordinary people suddenly start to work together as a collective. Previously everyone leaned on the film critic and Mr. Dury, taking their words as law, but now the dialogue is passing between a number of people like a relay pin, everybody contributing something. Their agitated enthusiasm from before has turned into sobriety and rational thinking, as they re-interpret the foreshadowing structure of Lady in the Water, to find other candidates for the magical people. Soon they succeed.

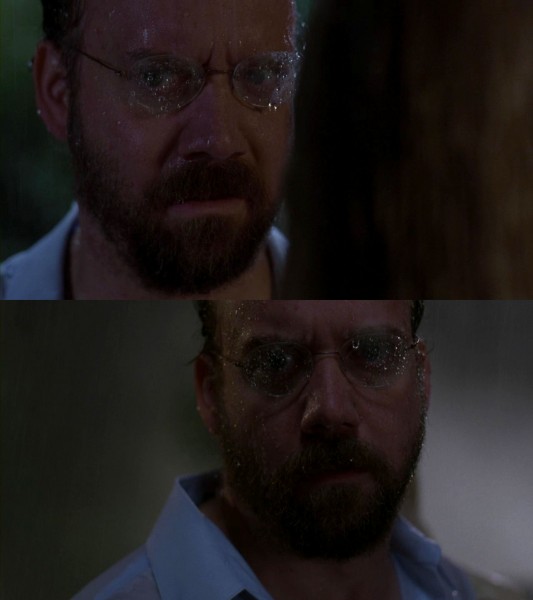

What makes their reasoning different from that of characters in a detective story? The latter would also limit their reasoning to clues that have been specifically announced to the reader in the course of the story. But they are not aware of themselves as fictional characters in that story. Together with all the rest of the self-reflexivity in Lady in the Water, this awareness gives the reasoning in the film a different flavour. The below frame grab from the scene incidentally provides an elegant nesting of self-reflexivity. As often in this film, the scene is shot in one take. Mr. Dury is the most prominently placed figure in the shot, for it is he who will finally come up with the answer. So at the same time that the characters are discussing the film’s foreshadowing structure, the shot itself foreshadows who will find the solution.

The presence of M. Night Shyamalan

In Shyamalan’s debut film, the little-seen Praying with Anger (1992), a very low-budget, charming but somewhat immature film, he plays the lead part as an American student, son of Indian immigrants, who goes to India to attend university and learn about the country of his ancestors. At one point he confesses his ambition of becoming a writer, about “love, important things”. The decision to cast himself as the writer Vic Ran – who writes about so important things that he is destined to change the world! – is thus a quite natural follow-up to the debut film. As discussed in the first article, Shyamalan’s decision to play the writer was met with extremely heavy criticism – critics saw it as impossibly self-aggrandizing. One important justification of his casting decision, however, is that it adds further complexity to the film’s self-reflexivity.

For example, fruitful parallels are created between Vick Ran on one side, and Story and Mr. Heep on the other. Story becomes a muse who helps realise Vick’s potential as a writer, in a similar way that the idea of a sea nymph was the inspiration that started Shyamalan writing Lady in the Water. The part of Story was also specifically written for Bryce Dallas Howard, adding self-reflexive resonance to the scenes between Vick and the actress actually embodying her. There are also other parallels. Like Vick Ran’s book will plant seeds in a child, Lady in the Water is meant to plant seeds in viewers in contact with their inner child. Like the book is to Vick, the film became an intensely personal project for Shyamalan, to such a degree that he burned his bridges with Disney and risked his entire career. In a late scene, Vick remains behind to safeguard the comatose Story while the others are rounding up the magical characters, as if Shyamalan is guarding his own story. The film also creates another connection between them, by both insisting that they are not “special”.

In the last shot of the animated prologue, the sea nymph is stretching her arms towards a lone house with a person inside, who sits bent over, probably writing something. Even though that shot’s sub-element of the lone person is assigned to Shyamalan in the end credits (see above), the narrative makes it meaningful to say that she is reaching out to two of the writers in the film. Vick Ran and Mr. Heep are the two people she gets closest to, the two with the most intense relationship to their writing, and the only ones actually seen writing. Since the character of Mr. Heep was another main inspiration for Shyamalan writing the film, it goes without saying that their scenes together too attain an air of self-reflexivity.

Let us stay for a moment with the importance of writing, Story and Mr. Heep. The first article made clear how much the diary he has written about his dead family means as a lifeline. As a wonderful and subtle metaphor for this, an emptied-out pen functions as a lifeline when Mr. Heep is breathing through it, sucking air from the upturned glass in Story’s cave. Furthermore, after his serious conversation with Mr. Leeds, who asks, “Does Man deserve to be saved, Mr. Heep?”, he (who answered yes) is seen to be writing with renewed vigour. Later, when he is “completing” Story by saving her and helping rebirth her into the more mature Madam Narf, “writing” is all-important. Mrs. Bell, who previously was thought to be The Healer, still manages to contribute to the healing by advising Mr. Heep, “Say something to bring out your energy.” Only by putting his grief over his dead family into words, he is able to save Story. On a non-writing note, it is striking that with her hair now having changed from red to blonde – it happened because of the scrunt attack but it is only now that it really becomes apparent – her hair colour matches the light green colour of the shirt she has been wearing throughout the film. So she has become complete visually as well, and the fact that it is her saviour Mr. Heep who owns the shirt only adds to the resonance.

They never meet in the film, but the inclusion of the film critic adds obvious layers to a film that features its critically-disfavoured director in a role. The critic’s statement that, “There is no originality left in the world, Mr. Heep,” becomes ironic since Lady in the Water is in fact very original. At one point it is said about the critic, “What kind of person would be so arrogant to presume to know the intention of another human being?” This is also ironic, considering that quite a few critics seemed to misunderstand Shyamalan’s intentions with the film, for example its humour. By the way, the critic’s complaint about film characters talking in the rain and his arrogant dismissal of Mr. Heep’s suggestion that, “Maybe it’s a metaphor for purification, starting new,” is commented upon by the purifying climax of Lady in the Water taking place in the rain.

In her long analytical review (in PDF), the American writer Colleen Szabo points out that the end credits Dylan song “The Times They Are a’Changin’” contains the lines “Come writers and critics / Who prophesize with your pen / And keep your eyes wide / The chance won’t come again”, which have direct bearing on the film. She also provides the brilliant observation that Reggie, the guy who only trains one side of his body, can be seen as a spokesperson for Shyamalan. In the scene that contains Reggie’s only lines in the film, he says to the newly arrived film critic, “You kind of look like maybe you could work out a little bit, right? I could give you a vein like that,” and later he calls his strange training strategy “an experiment”. What is really going on here, Szabo suggests, is that Shyamalan invites the film critics of the world to join him in the experiment that is Lady in the Water, and if they can hang on, he suggests the experience will strengthen them, give them a shot in the arm, so to speak. Just after, the Dylan song comes into play again. Its lines “Don’t stand in the doorway / Don’t block up the hall / For he that gets hurt / Will be he that has stalled” are directly echoed when Mr. Heep admonishes Reggie, “Don’t hang out in the stairwell… People might trip.”

In one scene one of the five smokers suggests that they should “make up a witty phrase.” He himself comes up with the idiotic “Blim-blam,” hoping for it to become famous. Later, when Vick’s sister comes to tell Vick that Mr. Heep wants to deposit the injured Story in their apartment, she says, “She’s wearing no clothes under his shirt. Blim-blam. Mr. Heep is a player.” The phrase seems to have caught on after all, denoting something naughty. Vick is slightly taken aback, as if he does not know the expression. But the way Vick is shot also opens up for a double meaning of the situation, in the form of self-reflexive joke. We see his electric typewriter in the background, the framing providing a relatively unobstructed, somehow meaningful, view of it. If we substitute Vick Ran and his book with Shyamalan and his film script, it is as if Shyamalan is taken aback that the phrase he invented for the smoker – in the process making it so idiotic that it should never have caught on – somehow has escaped the smokers scene only to turn up elsewhere in the script. It is a joke about a writer whose script has taken on a life of its own.

Directing, play-acting and artificiality

A less important, but still sufficiently prevalent device that draws attention to Lady in the Water as a film, is the fact that several of the scenes are “directed” by one of the characters. Mr. Heep is telling Vick Ran’s sister and Mr. Dury what to do in, respectively, the children’s game scene (with the film’s real director lurking in the background) and the interpretation scene. He is also staging the scene where Vick Ran is supposed to be awakened by meeting Story. The Korean girl is miming instructions to Mr. Heep to make him pretend to be a child in the optimum way to please her mother. When Mr. Heep goes to confront the scrunt, Story is transmitting by walkie-talkie very specific instructions about his behaviour.

In the first article we have already talked about the opening scene, where the exaggerated acting of the Mexican daughters and the fact that we cannot see the bug, lend an undercurrent of artificiality and play-acting to the scene. Play-acting is especially important in the scene where Mr. Heep pretends to be a child. The way Paul Giamatti goes about it has been criticised for being way too obvious, but that is missing the point. For the scene fits perfectly with the playful attitude that dominates the film’s central section, and Giamatti’s outrageously exaggerated acting is clearly intentional. With a tray of cookies placed in the foreground as if having an iconic property, he turns the scene into an ingenious blend of something highly ironic and deceitful on one hand, and something utterly sweet and disarming on the other – a shameless parody of the behaviour of an ingratiating child miraculously leads to something innocent, pure and childlike. The scene is ostensibly about being so convincingly child-like that the Korean mother will tell Mr. Heep the rest of the bedtime story. It starts out as a suspense scene, where a clearly nervous Mr. Heep has to overcome his fear of the mother to achieve his objective. But it soon turns into something else. The way it is staged foregrounds acting itself, with an air of carefree “we’re just playing here” attitude, as if we are witnessing something out of improvisational theatre, or improv comedy. In this reading, Giamatti is putting on a pantomime show, milking everything to its last drop, trying to get his audience, the harpy-like Korean mother, to laugh. When it finally happens it seems so natural that I suspect this is not acting – possibly June Kyoto Lu playing the mother was instructed not to laugh at all costs, but ultimately could not help herself. Both mother and the broadly-smiling daughter, in fact, seem totally out of character here, simply delighted by Giamatti’s antics. The fact that we can hear Giamatti laughing off-screen at that very moment only adds to the impression. So through parody and artificiality, the mother and her otherwise so farcical daughter are humanised and behave like carefree children. The idea of the scene is childishly simple yet brilliantly operates on many levels at the same time.

A scene scoring high on artificiality is the situation where Mr. Leeds suddenly puts into words an important theme: “Does Man deserve to be saved, Mr. Heep?” The bluntness and solemnity of the question; the fact that he until then has not said a word in the film; his rigid and unnatural position in his chair; his unblinking stare; the exaggerated sound effect when he just before held up the sheet of paper with the invitation to the big party; the high number of lit lamps in the shot as if they are shedding light on the theme – all this adds up to an impression of artificiality. Not to speak of the rule-breaking Shyamalan indulges in here – actually, it is so blatant that it seems intentionally emphasised – for in films one is not supposed to let characters spell out themes in such obvious fashion. A fascinating thought, by the way, is that Mr. Leeds may in some way represent God, but a deity that has withdrawn from the world in disgust over the human race He created. (Mr. Heep’s statement that “He’s been here forever” suggests immortality.) This God angle gives his question a different, introspective tenor, and Mr. Heep’s positive answer may be more important for mankind than it appears.

Claiming that a lamp can shed light on a theme, as above, is of course very literal-minded, but interpretation can often be surprisingly literal. Shyamalan seems to emphasise this through his creation of the magical character called The Man With No Secrets. The reason he lives up to that identity is that his wife cannot stop blurting out his “secrets” of various unsavoury bodily imperfections. It is a foreshadowing that is at the same time horrendously obvious and slyly hidden, since its very silly literal-mindedness obscures the connection. Part of the film’s humour arises from the businesslike way with which such ridiculously literal interpretations are presented, as with the little boy who can read meanings out of the ordinary.

We shall conclude this chapter with an elegant situation, illustrated by the frame grabs below. Here Mr. Heep hears splashing from the pool, something that will eventually lead him to meet Story for the first time. A typewriter is placed strategically on the table in front of the window. A typewriter can be used to write stories and the very old type of instrument suggests ancientness – both elements connect directly to Story and her ancient Blue World. The elegance of the shot is further increased, since there is water both in the background (the pool) and the foreground (almost hidden, Mr. Heep seems to be splashing water on his face). Later that night, when Mr. Heep and Story leave the house and will confront the scrunt, a new element of the bedtime story, the typewriter is again prominently placed in the shot. We also note that the typewriter creates yet another connection between the two most important writers of the film, since Vick Ran is using an electric typewriter rather than a computer. Even Vick’s modern typewriter manages to suggest ancientness, since its usage is thoroughly out-of-date in our day and age.

The interconnectedness

In a much more difficult role than her exuberant character in The Village, Bryce Dallas Howard‘s possibly finest moment in Lady in the Water comes when she tells Vick Ran in an exquisitely soft voice: “Man thinks they’re each alone in this world. It is not true. You are all connected. One act can one day affect all.”

The message may seem banal, but there is nothing simple-minded about how interconnectedness and collaboration are manifested in Lady in the Water itself. For starters, consider how the bedtime story is unfolded throughout the film. We have a Korean woman in the rather distant past, before the film’s time frame, who tells the story to her granddaughter. That granddaughter is identical to the Korean mother in the film, who tells the story in instalments to Mr. Heep using the Korean girl as interpreter. (The Korean girl also tells the story directly to Mr. Heep on two occasions, but she merely repeats what her mother has told her.) Throughout the film, the following people are involved in telling the story, or information very important about the story, to the others (in correspondence with the ten stages described in appendix 1 of the first article): the Korean mother (stage 2 and 5), Story (stage 3 and 9), the Korean girl (stage 4 and 6), Mr. Heep (stage 7), the Symbolist/Interpreter embodied by Mr. Dury (stage 8) and the Symbolist/Interpreter embodied by Mr. Dury’s son (stage 10). Speaking of storytellers, however, we must not forget the earliest one of all, the voice from time immemorial: the voice of the myth itself (possibly performed by Bill Irwin, who plays Mr. Leeds) who tells of its background over the animated images of the prologue.

So there is a chain from the past to the present, and this present involves a whole collection of people all doing their share. But there is also another chain, from the present to the future. (This mirrors, by the way, how the characters of the film are interpreting both the past and the future of the film itself, as described in a previous chapter.) Story meets her vessel, who turns out to be the writer Vick Ran. The encounter with Story enables him to realise himself fully. He finishes his book, The Cookbook, and then in the words of Story: “A boy in the Midwest of this land will grow up in a home where your book will be on the shelf and spoken of often. He will grow up with these ideas in his head. He will grow into a great orator. He will speak and his words will be heard throughout this land and throughout the world. This boy will become leader of this country and begin a movement of great change. He will speak of you and your words. Your book will be the seeds of many of his great thoughts. It will be the seeds of change.”

This vaguely sounds like an idealised version of President Obama, still just a Senator when Shyamalan created Lady in the Water. But the important thing is how this explanation emphasises the chain. It is not just a man who read The Cookbook and became a leader. No, he is first a boy and it is through his parents that he becomes familiar with the book. And the words of that book are not necessarily fully developed golden nuggets – it is emphasised that they are seeds that develop into something else. In a similar way, the Korean mother says that her own grandmother said that she “knew someone who knew someone” who saw a narf. This is definitely not supposed to be a simple and forthright story! Again a chain is emphasised, but through space instead of time.

Collaboration and the passing on of information are further emphasised throughout the film. Story herself has been taught about the myth and states at one point that, «It is only what I have been told by others.» Not only is there translation of the myth from Korean, but the Mexican father translates his daughters’ belief in creatures of the devil. The characters collaborate smoothly after the film critic has died, and when that scene ends with Mr. Dury getting the idea, the solution rests not with him but with his son. When Mr. Heep’s “big speech” during the resuscitation scene ends with “I love you all so much,” this is not only directed towards his dead family, but to everyone in the room, and, for that matter, all of Mankind. Playing in unison with all this is another kind of interconnectedness, namely the vast network of interrelated motifs and parallels that not only runs through Lady in the Water, but all five films in the series.

The children’s game

The next chapter is dedicated to a visual analysis of Lady in the Water. The marvellously joyful children’s game scene so central to the film – and arguably its best – will be analysed there. But there is so much at play in that situation, so first it ought to be briefly discussed to put the later visuals in full perspective. Story, who is not supposed to say too much about The Blue World, is here persuaded to take part in a game where, instead of words, she is to answer by touching parts of her body.

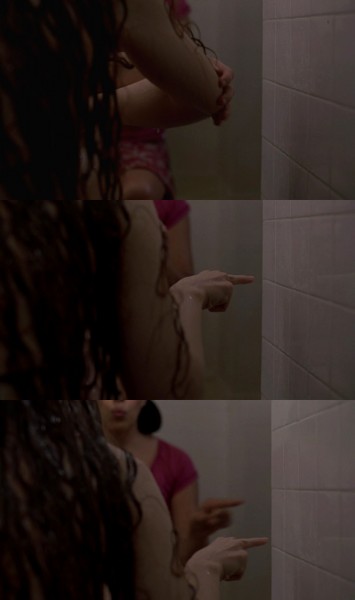

In this scene we have co-operation, harmony, the pleasure of finding things out, playfulness, friendliness, human beings shown in their best light, the joy of staging a film in interesting ways. But also elements in an opposite, artificial direction: sign language instead of speaking, stylisation, geometrical camera movements, a Brian De Palma-style overhead shot revealing it all to be a film set, a Wes Anderson tendency, reminiscent of Signs, to shoot things frontally or from the side. The scene is full of contrasts: the talkative sister vs. the silent Story, wild unpredictability of content vs. relentlessly strict formal staging, the mundanity of the bathroom setting vs. the monumental implications of the conversation, the childlike abandon of Mr. Heep’s questioning vs. the stylised ritual of answering – plus the ballet-like hand movements and the hypnotic quality of the entire scene.

One of the best things in it is how Vick Ran’s sister, who until now has often been an irritating figure, here blooms into such a sweet and charming character. She is still somewhat caricatured, but is shown as intelligent, emphatic and down-to-earth. She has been gesticulating all through the film, but this has probably been as a foreshadowing of her hand movements in this scene (and also of her future membership of The Guild, whose hands are important). Her use of hands also echoes the stylised hand movements of the animated prologue.

As regards themes, here is an edited version of Aubrey Wanliss-Orlebar‘s description from the previously mentioned conversation in the film periodical Z:

“In the central scene with the children’s game, many of Shyamalan’s themes intermingle magnificently. Here we have an innocent character representing the virtue and the goodness, the truthfulness and ability to listen that humanity has lost. There are also the themes of secrets, of childlike innocence embodied in characters who will do a great deal of good and have a healthy influence on others, of such characters acquiring faith in themselves and realising their importance, of a mentor or a whole community helping such characters, and of the ritualised revelation of the secret, here through the children’s game. All of these themes of Shyamalan’s films are given form at the same time. It is a quintessence of his art.”

Visual stylisation

The rest of the article consists of series of frame grabs illuminating key scenes of the film. Lady in the Water often has a stylised feel and Shyamalan employs a wide range of tools to achieve it. This is not restricted to camerawork, but it still is useful with a brief overview of that area. Several scenes in Lady in the Water are shot in single, long takes. Like his idol Steven Spielberg, Shyamalan eschews the staging of dialogue scenes as a series of over-the-shoulder shots, the mechanical method so often employed by lesser directors. As a stylist, however, he is much bolder and stylised than Spielberg. He is not afraid of introducing a measure of artifice in his mise-en-scène, for example “geometric” use of the camera, such as lateral camera movements. He has always been fond of overhead shots, and Lady in the Water breaks the record with as many as nine. (I do not count the late shot of the eagle flying over city, since the camera eventually tilts up to follow the bird, which will end up above the camera.) One aspect that his new cinematographer for this film, Christopher Doyle, has brought into the equation seems to be a higher awareness of the use of focus.

Let us start out with the horror elements of Lady in the Water, which are not as frightening as in the previous films. The scene where the scrunt suddenly breaks through the window to attack Story, however, is a quintessential horror moment. From a director whose Signs was virtually a re-imagining of Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), the aliens replicating the function of the earlier film’s bird attacks as an expression of existential fear, it should not come as a surprise that similar things are going on in Lady in the Water. The highly inventive decision of leaving the monster out of focus in this scene suggests metaphor, that it represents a half-shapeless embodiment of some primal fear inside her, brilliantly captured in the below frame grab:

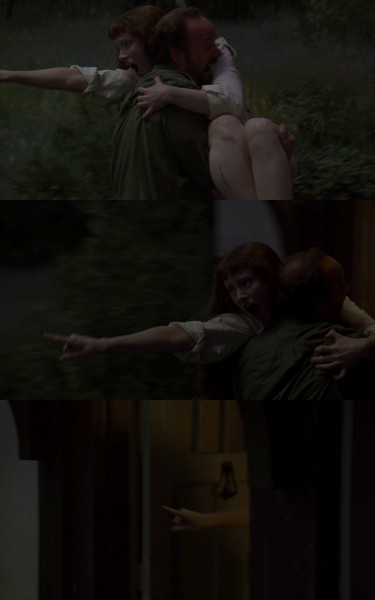

The scene of the first scrunt attack is another expression of the basically same primal fear, but here rooted in a child’s world – the couple’s uncontrollable panic should be recognisable for anyone who was ever afraid of the dark as a child, running away in blind fear from unspeakable things in the shadows right behind us. The stylisation is here achieved through a wide variety of means.

Now for the children’s game scene, described further in a previous chapter.

The next scene details a conversation between Vick Ran and Story about his future fate. This too is (partly) staged through stylised camera movements.

The climax, with the final stand-off with the scrunt and the appearance of the Tartutic and the giant eagle, is clearly intended as awe-inspiring and spiritually uplifting. It never really worked for me on that level but it grew on me on repeated viewings as I became conscious of the stylised approach to mise-en-scène in parts of the sequence.

The swimming pool has a fascinating shape. It could look like a heart or a fish, but an eye seems the most plausible interpretation.

If one is so inclined, one could take the above interpretation further by pointing out the similar oval shape of the pool and Story’s face, and the inversion between those shots: the pool is a dark shape surrounded by something brighter, while her face is a bright shape surrounded by something dark.

Below is the start of the party scene. The overhead shot of the pool sums the film up nicely. Story from The Blue World lives beneath the pool and clouds are reflected in its surface, signifying from where the giant eagle will come. The bright object inside the dark area in the left part is the grating Mr. Heep swam through to get the Kii (the magic mud). In a nice touch, the steps leading down into the pool near its pointed tip are virtually directly lined up with the concrete steps to Mr. Heep’s house, somehow signalling the inevitability of him meeting Story. The pointed tip of the pool conveniently points in the general direction of where the final showdown between the scrunt and the Tartutic will happen. When the camera moves one can see the dirt path leading to Mr. Heep’s house.

Interpreting the pool as an eye is further strengthened by the two scenes where the camera is looking up from underwater, as if from a metaphorical vantage point of beings from The Blue World gazing into our world. The first scene (below), where Mr. Heep slips, hits his head and then falls into the pool, is in fact from the concrete viewpoint of Story, who hides in the pool at that moment.

Now we come to the moving and subtle ending of Lady in the Water. It too is stylised, but in a totally different way than the rest of the film, relying heavily on this distorted view from an underwater camera. Taken as a vantage point from beings from the Blue Word, the ending then beautifully links to the prologue with the narfs in the water addressing human beings on the shore. Other than that interpretations are legion.

Since the underwater camera was Story’s viewpoint in the shot above, the current position could indicate that she symbolically returns to water even though disappearing into the air with the eagle. The distorted and filtered property of the camera’s gaze could serve as an indicator of the alienness of The Blue World, a magic veil or signify the impermanence of existence. It is also tempting to make the connection eye – soul – pool – the pool of the soul – the unconscious. In that case it is fitting that Story’s “apartment” is below the pool, filled with water, the archetypal signs on its wall somehow part of humankind’s collective unconscious.

This is definitely not an ending to be expected from a mainstream Hollywood film. It virtually ignores the potential spectacle of the arrival of the eagle, turning it instead into a very subtle, almost experimental film. Its simplicity and stylisation also echo the minimalist approach of the animated prologue.

I hope that through these two articles I have showed that Lady in the Water is not the dismal failure it is known as, but a very interesting film that pushes the envelope of what can be done in mainstream cinema.