The Sixth Sense, Part I: Stature and Style

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the first article about The Sixth Sense. The second is here, the third here. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

Upon its 1999 release, The Sixth Sense became famous and a tremendous world-wide commercial success. Its qualities are obvious. Haley Joel Osment was a revelation as an achingly engaging child actor. Toni Collette is highly convincing as a beleaguered lone mother trying to cope with her son’s apparent mood disorder. A cast-against-type Bruce Willis provides subtle and solid support. The story feels original and is intelligently organised with crisp efficiency. It is emotionally gripping and dense with atmosphere. The film’s climactic plot twist is shocking, and very few saw it coming – even though it is “hidden in plain sight”, with immense control and audacity. Even better, the core thematic values of the film are so strong that on repeated viewings the shock is replaced with a highly satisfying emotional resonance.

The film’s “domestic” horror moments – during breakfast or tidying an apartment – are subtle and inventive. Its more traditional horror scenes are executed with razor-sharp precision, and in the case of the vomiting girl, realised with a rare mixture of disgust and compassion. Additionally, The Sixth Sense is one of the few genre films that truly discuss what horror really is, by filtering it through the experience of a frightened small child. Indirectly, it is also discussing misdirection, an all-important part of a illusionist’s craft, in the form of the “magic trick” of hiding the plot twist.

So the qualities of M. Night Shyamalan‘s signature film are evident. This analysis will be devoted to exploring some important aspects that one feels have received less attention. In this first article I will discuss how unique Shyamalan was as a filmmaker during his heyday, starting in 1999 and continuing into the early 2000s. Then I will consider his general approach to style, form and mise-en-scène, and briefly examine some stand-out scenes of The Sixth Sense to ascertain their distinctiveness and also to demonstrate Shyamalan’s versatility as a director.

The second article contains an in-depth analysis, heavily supported by frame grabs, of the opening scene and the last three scenes of the film. To an unusual extent, the opening scene is densely layered with ambiguity, foreshadowing and subtle information. There will also be an extensive analysis of the film’s three different, tonally highly distinct “endings” – the last scenes are all marked by finality, redemption and resolution. Possibly the greatest feat of this magnificent film is how M. Night Shyamalan is achieving closure on a head-spinning number of levels, emotionally as well as thematically.

The third article explores some of the film’s structural aspects, themes and motifs. For example the general carefulness of the film’s construction, the use of backgrounds to unconscious effect, and some of the more subtler aspects of the otherwise obvious motif of the colour red. Furthermore, the themes/motifs of violence, ancientness vs. modernity, the connection between statues and ghosts, female/male, time/timelessness, pretending/artificiality, rituals, secrets, thrice-occurring elements. It will end with an analysis of the post-funeral sequence, which constitutes a short film unto itself within the larger structure of The Sixth Sense.

For a general summary of the main themes and motifs of the five films in the series – which could be useful as a general introduction to this article for readers unfamiliar with Shyamalan’s work – please click here.

Through the following, one must not forget that Shyamalan is heading a team of excellent collaborators. As in most film criticism, when the writer is saying “the director does this, the director does that”, it is a rhetorical device that in no way is meant to belittle the efforts of his team. Shyamalan also wrote the screenplay for The Sixth Sense, however, and the themes, motifs and approach are generally the same for all five films of the series, with different collaborators, so it seems safe to assume that he is indeed the major guiding light. Furthermore, the article does not, of course, imply that every item detailed in the analysis has ended up in the film through conscious decisions on Shyamalan’s part. If interesting patterns have been found in the analysis, however, they ought be examined regardless of their intentionality.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of The Sixth Sense, here is a brief outline of the premise.

This first article mainly discusses the film on a general level, but it is difficult to analyse the film properly without revealing the big plot twist. This will be done, however, in very indirect fashion.

The special case of M. Night Shyamalan

These days, M. Night Shyamalan is so abysmally out of critical favour that it is useful to think back to his halcyon days in the early 2000s to remind ourselves how unique he was. His origins were decidedly inauspicious, however. First he made the extreme-low-budget, largely ignored Praying with Anger (1992), and then he suffered the common ignominy of having another very personal work, Wide Awake (1998), taken away from him by the notorious Weinstein brothers so they could do with it as they pleased. From this position as a humiliated pawn in the commercial movie game, he catapulted overnight to become virtually the King of Hollywood. (Such a sudden elevation must be unique in the annals of Hollywood – Terrence Malick and Orson Welles spring to mind artistically, but were far from reaching the same popular appeal.)

Shyamalan wrote a screenplay that was so gripping and smart that every studio was desperate to get it. Not only did he orchestrate the following bidding war completely on his own terms, but this former nobody had no problems securing the directing reins for himself, even with a right to final cut, something that normally eludes but a handful of the most exalted Hollywood directors. The Sixth Sense (1999) went on to earn more than one billion dollars in world-wide ticket and DVD sales as well as broadcasting rights. The line “I see dead people” achieved instant iconic status in popular culture. He made a star out of Haley Joel Osment, one of the most impressive child actors ever. All this before he had even turned thirty.

The remarkable thing is that M. Night Shyamalan did all this on talent alone. Based in Philadelphia all his life, at that time he did not have particularly good connections in Hollywood. There were no smart gimmicks to drum up interest in the screenplay, just the quality of the content. The marketing of the finished film did not hide the fact that this was a movie that required audiences to think, so one cannot say anyone were lured on false pretenses. There is an elegance, precision and perfection in the pacing, editing and staging of the film that is quite unbelievable from someone close to being a first-time filmmaker. There is a seriousness and emotional resonance to the acting and treatment of theme – at times the film is almost brutally unflinching – that is unheard of for such a huge commercial success, not to speak of a film from a company within the Disney organisation. The violence that creates the ghosts is virtually exclusively rooted in unglamorous, topical issues like domestic abuse or lack of gun control.

At the same time, his very approach to filmmaking flies directly in the face of how one is supposed to make movies today. Just take a look at The Sixth Sense‘s credits sequence – the deliberate pacing and sobriety of the image-free title cards exude classicism and “old-fashionedness”. For in an age of shortened attention spans and fast editing, M. Night Shyamalan is making very, very slow films. In a time where movies are supposed to be spectacular, loud and laden with effects, he is creating somber and hushed films. In mainstream Hollywood films, where crime is normally treated as something to excite the audience, when the murderer is revealed/subdued in respectively The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable, there is no payback, no revenge, no sense of triumph, just an immense sadness about the violent nature of humankind. In a storytelling climate driven by “rapid eye movements”, many scenes in his works, including The Sixth Sense, are shot in one long take, a strategy that is supposed to bore audiences to death. Finally, in an industry environment where transparent style and realism reigns, he is not afraid of formal invention and stylisation – in fact he eagerly embraces it.

I am not saying that M. Night Shyamalan is more distinct than the Coen brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson and many other current filmmakers of singular talent. But what was unique about him in his heyday is that he was a highly distinct filmmaker operating in the uppermost stratum of commercial success – a moneymaking machine that doubled as a challenging artist, constantly striving to push the envelope. At that time, during his fertile period from late 1999 until The Village in 2004 (with Lady in the Water as an interesting and woefully under-appreciated epilogue in 2006), many of his artistic competitors experienced a rather fallow period. David Fincher, someone not that far away in box-office ambitions, scored artistically with Fight Club at the same time as Shyamalan’s breakthrough, but during the rest of this period he could only offer the somewhat pale Panic Room (2002). Two of the four Coen brothers films of the period – Intolerable Cruelty (2003) and The Ladykillers (2004) – are generally regarded as their least successful efforts. At the outskirts of Hollywood, such an ultra-distinct figure as David Lynch only made one work of absolute merit, Mulholland Drive (2001), during the period. A more dangerous contender, perhaps, is Paul Thomas Anderson with Magnolia (1999) and Punch-Drunk Love (2002), but he falls short in productivity. In fact, a good case could be made that it is only Shyamalan’s idol Steven Spielberg – curiously experiencing an extraordinary creative surge and productivity during the virtually exact same period – who can rival M. Night Shyamalan as the best American director in 1999-2004. (It is hard, however, to imagine Spielberg making such a brilliantly original work as The Village.)

Style and mise-en-scène

Shyamalan’s arguably greatest strength – and an aspect of his work that seems too often overlooked – is his command of style and staging. Craftsmanship and artistry come together to give each scene a formal distinctiveness and a visual enhancement of its themes and emotions. Like Spielberg, as touched upon in my analysis (in Norwegian) of Munich (2005), he prefers to combine several storytelling elements into one longer take by camera movement, rather than cutting between them. His stylistic choices are generally much bolder, however, than Spielberg’s more understated, classical approach. Shyamalan enjoys self-aware, at times outright distancing, stylistic devices like overhead shots and, especially, geometrical camera movements, for example extended lateral movements. This stylistic strategy has a lot in common with Stanley Kubrick, but Shyamalan’s warmer, more character-oriented concerns keep him at a safe distance from Kubrick’s severe, sardonic universe of alienation. This article is not going to be a comparative stylistic analysis, however, but as a simplified indicator of Shyamalan’s film-formal position, it may be helpful to think about him as a cross between Spielberg and Kubrick.

The signature of Shyamalan’s film-making approach will become much more pronounced in the next four films in the series, especially in Unbreakable and The Village. In The Sixth Sense, the more audacious aspect of his personality is somewhat reined in, possibly by a relative newcomer’s concern not to screw up a screenplay so gripping on a human level that it would have a sure-fire mass appeal. As mentioned in the previous chapter, by ignoring modern movie-making trends, the concept was bold enough already without risking alienating audiences with self-conscious stylistic choices, regardless of their artistic merit. Even within the more cautious framework of The Sixth Sense, however, most of his formal preferences are already in play and most of its scenes are distinctively staged.

Methodical piece play

Perhaps the thing I like most in Shyamalan’s best works is the feeling of a relentless methodicalness. I do not know if Shyamalan plays chess (Kubrick was a great enthusiast of the royal game) but it would not be surprising.

In chess you cannot put the piece wherever you want on the board, it must either be on this square or that square – there is no in-between space, no room for compromises. And M. Night Shyamalan puts each piece right in the middle of the square, with exquisite neatness. Sometimes the mise-en-scène feels almost like well-oiled machinery, and his pleasure in precision and geometry virtually radiates from the screen. Consider this brief shot in the scene where Cole and his mother Lynn have been invited to one of his classmates’ birthday party. Some boys have trapped Cole in a big closet at the top of a staircase and his screams are almost drowned out by the loud party music.

In just one fluid go, the shot has accentuated the obliviousness of the other mothers, addressed Lynn’s apartness and alienation in relation to them (they belong to a much higher social class), fixed her position geographically in relation to Cole at the top of stairs, used the upward-slanting banister to reinforce the direction of her gaze, and maintained the staircase as the central visual motif of the entire scene, somehow having drawn Cole upwards to his doom. Another good example of Shyamalan’s geometrical neatness is the last three shots of the opening scene of Anna fetching wine in the basement. Here the camera placements together exactly represent three sides of a square-shaped box – the walls of the cellar – while Anna herself is always facing one side or another of the box. (This scene is further explored in the second article.)

Shyamalan’s fondness for visual neatness and geometry does not govern every scene – that would be stifling, of course – but his chess-player-like attitude informs the whole film, in its careful thinking out of a methodical strategic plan. Another all-important ability if a chess player is to master the game is pattern-recognition – a mostly unconscious process of scooping up a vast amount of detail in order to consciously become aware of a favourable idea or strategy. In cinema the details would form hidden strands of motifs and thematic elements that could nudge the viewer’s unconscious, most often through repeated viewings, into becoming aware of conscious ideas that will enrich the experience of the film.

Kubrick was obsessed with patterns and wove a large amount of them into his films – perhaps most of all in The Shining (1980) – and Shyamalan seems to be no slouch in that department either. (We will return to this while discussing the prologue and endings of The Sixth Sense in both the second and third article.) But despite all his fondness for geometry and patterns, Shyamalan still does not come across as an obsessive. There is a fundamental naturalness to his ways that puts him in a different playing field, compared to an otherwise kindred spirit like Wes Anderson, the demented genius of patterns and artificiality. Finally, Shyamalan’s methodicalness is again revealed in his use of point-of-view shots. Especially the ones with a moving camera in the suspense scenes with the ghosts – and his ability to draw the audience in with them – would have made Hitchcock proud.

Staging slowness

Let us have a look at some of the scenes of The Sixth Sense to try to ascertain their distinctiveness and also to demonstrate Shyamalan’s versatility as a director. A situation that automatically springs to mind is the magnificently orchestrated restaurant scene where Malcolm has arrived unforgivably late for a marriage anniversary dinner with Anna. Filmed in one long, two-minute take, starting with Anna’s back to the camera, then closing in on their table and finally turning around to reveal her face – all of this excruciatingly slowly – the scene is a tour-de-force of atmosphere, elegance and mystery. From my first viewing, I remember vividly the completely bewildering bizarreness of the situation. The loving couple from the prologue have degenerated into dysfunction to such a degree that the wife is so disgusted with him that she cannot even bear to acknowledge his existence. What disaster could have torpedoed an apparently ideal relationship?

Even after learning the reason by the end of the film, this situation – together with the hushed scenes where Malcolm arrives home to his wife – remains upon repeated viewings a powerful and poetic metaphor for a breakdown of marital communication. This is in large part due to the peculiar atmosphere, which originally arises out of the need to hide the film’s plot twist, but this technical need has given birth to something very artful. Like the shock of the twist ending is replaced by emotional resonance upon repeated viewings, the fact that the restaurant scene keeps on exerting its hypnotic fascination even though we now understand what is really going on, speaks volumes about the enduring, fundamental values at play in The Sixth Sense. The common accusations that M. Night Shyamalan is purely a gimmicky director can hardly spring from any real engagement with his work.

The most emotionally powerful situation in The Sixth Sense is undoubtedly the late scene in the car where Cole finally reveals to his mother the cause of his problems. This is a statically shot, mostly character-driven scene, but the long-take build-up is extraordinary. Clinging strangely low to the ground – reminiscent of one of the suicide scenes in The Happening (2008) – the camera moves quite leisurely from cars involved in a traffic accident, then along a long queue of vehicles having to wait until the accident is cleared up. The first dialogue from the scene’s protagonists appears after 20 seconds, when the camera is about half-way to their car. They continue to speak as the camera with imponderable slowness reaches the car after 25 more seconds, then keeps on looking in through the window to cover further conversation for slightly more than a minute.

One reason for the camera movement might be to indicate the path of the accident victim’s ghost that will soon appear beside their car. The main reason, however, seems to hold back information. This is a strategy employed right from the start of the film. On the whole, Shyamalan in this film shows an uncanny ability to predict audience reaction. Producers were nervous that the midway, crucial scene where Cole finally tells his secret to Malcolm was edited in a way that would give away the climactic plot twist. Shyamalan was confident that virtually no one would guess. He was also correct in judging that viewers would be so engrossed in the characters and story that he could employ slowness and holding back information as deliberate tools to heighten tension and engagement even further. Audiences would already be so gripped that the slower the film moved, the more they would crave to know what came next.

The Sixth Sense must be one of the few Hollywood films, and surely the only gargantuan commercial hit, that virtually grows slower the closer it gets to the end. Admittedly, the six-minute final scene eventually proceeds at a brisk pace, but consider the eight-minute post-funeral sequence near the end. Seldom has the term “funereal pace” seemed more appropriate. Dominated by long takes, camera moving at a snail’s pace, in one scene it takes ages – see the frame grabs below – for Cole to find the father of the dead girl and give him the box with her videotape. This is followed by a shot of the box, which the father opens very, very slowly. (We will return to this sequence in the third article.) Soon after this sequence, the camera tracks in on a theatre stage for half a minute. In addition to all the other peculiarities indicated at the start of this article, the more one looks at The Sixth Sense, the more unbelievable it becomes that this could be, practically speaking, a Disney Film, and one embraced by an enormous, world-wide audience – in a day and age where films are generally marked by rapid editing for audiences with supposedly diminished attention spans.

Furthermore, the dialogue and character interactions are full of pauses, and the screenplay is peppered with the instruction “Beat” to indicate them – reading it becomes almost comical when Shyamalan commands “Cole takes an eternal pause” before the boy is allowed to utter his momentous “I see dead people”. This deliberate slowness is built into the film even at a minuscule level. When Cole is bored in class we see him move a pencil by blowing his breath on it. Most filmmakers would have thought that had made the point, but Shyamalan calmly makes Cole repeat exactly the same action. Later, Malcolm starts hearing strange sounds on the audiotape of an all-important old case. When Malcolm wants to turn the volume dial to full, however, it is not sufficient with one finger movement. While the audience is aching to find out more, Malcolm has to move his finger again to reach top volume. This almost sadistic way of making the audience wait, as if teasing someone whom he knows he has in the palm of his hand, is a trick from Hitchcock’s playbook. Here the wait is only for a short moment, but, as we have seen, it is part of a strategy that informs the entire film.

The average shot length of The Sixth Sense is 8.7 seconds (my own calculation, and with company logos, credits and end credits excluded from the running time). The average is dragged down by quite a few scenes featuring heavy editing, but this is still significantly higher than the typical modern Hollywood film. Much more unusual for such a type of film, however, is the fact that as many as 24 shots clock in at 30 seconds or more. The longest takes are all, somehow, connected to food: dinner between Cole and his mother (160 seconds), the restaurant scene with Malcolm and his wife (118) and the breakfast scene with Cole and his mother (112). Long takes may contain frenetic action, of course, but generally the average shot length is a pretty good indicator for a film’s pace. In Unbreakable, which for Hollywood is an almost experimental film, a cross between Brian De Palma and Andrei Tarkovsky, the ASL shoots up to a majestic 18.9 seconds, which is slightly more than art film classics like Antonioni’s L’avventura (1960, ASL 17.7) and The Passenger (1975, ASL 18.6). Using deliberate pacing as an artistic device is yet another link from Shyamalan to Kubrick, for example in works like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Barry Lyndon (1975).

Long-take cutting

The film’s longest take is interesting in another way. It starts out including both Cole and his mother, but as the camera creeps ever closer to the dinner table it starts to softly pan to the left and right, ultimately “dividing” the scene into five one-shots, alternating between the two of them, until the scene ends with a perfectly framed close-up of the mother, angry that Cole has denied taking her bumblebee pendant. The naturalness of the acting and the stunning technical precision of the shot create a discreetly dissonant contrast. The ever-tighter, intensifying framings – the shot is basically an elegant modernisation of classic Hollywood-style editing – illustrate how their communal experience of having dinner is helplessly transformed into a situation where their inability to communicate creates an expanding, in the end completely isolating, gulf between them.

Holding back information is at play here too, since as the camera progressively concentrates on one of the characters, we see less of the other one. The less we see of the mother, the more hard and unforgiving her off-screen presence seems. And when the camera pans back to Cole after having stayed with her for a while, the sight of him hiding his crestfallen face in his hands seems all the more shocking since his prolonged off-screen status has made us more curious about how he is coping with the situation. His posture seems also more shocking than if there had been a direct cut to him, because the panning movement creates a relentless, excruciating feeling – as if a sharp object is slowly screwed into a wound – inexpressible by editing. While we are at things off-screen: off-screen sound also contributes to this scene, but the crowning achievement of this device in The Sixth Sense is during the post-funeral-sequence. While we stay with a close-up of Kyra’s father watching the video, we hear the sound of poison being poured and a spoon stirring the soup. Being forced to only hear the sound somehow makes the situation even more devastating and sickening.

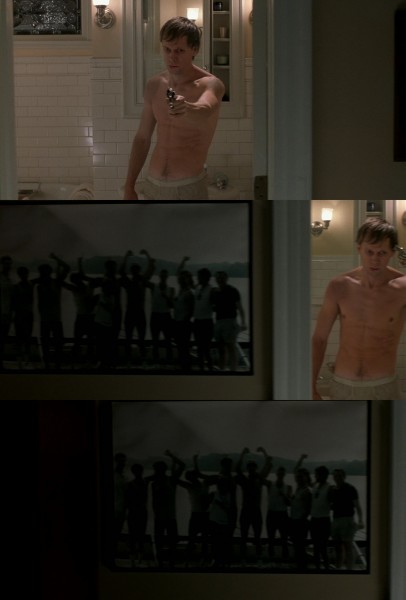

Even more sickening is the brilliant shot in the prologue where the intruder Vincent Grey (an intensely focused Donnie Wahlberg) shoots himself in the head as the camera tracks past him. The revolver goes off at the exact moment that his head has disappeared off-screen. An inventive way to avoid a higher rating than PG-13, perhaps, but instead of Vincent’s head, it is the viewer’s head that explodes, with self-generated images almost in the way audiences swore they had seen a knife enter Marion Crane’s body in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). The devastating effect of the scene is heightened by the camera movement ending, in deadly ironic contrast, with a picture on the wall of Malcolm’s triumphant rowing club team. Incidentally, Shyamalan has a knack for creating situations that remain equally sickening no matter how many times the films are watched: the sound of Mr. Glass’s bones breaking as he falls down the subway stairs in Unbreakable, and the sight of the red-caped creature that confronts Ivy in the forest in The Village, are comparable moments to Vincent’s death.

The camera movement past Vincent is lateral, and a similar device is employed in miniature earlier in the scene. As Malcolm tries to recall the name of a previous patient to match Vincent’s grown-up features, on his first two attempts he is shot in close-up but the camera is gliding laterally past him, to visually mimic how his mind is searching for the name. On his third and correct attempt – incidentally, there seems to be a pattern of thrice-occurring elements in the film that I will go into in the third article – the camera is stationary again. These three shots are cross-cut with shots of Vincent that exactly match: close-ups with a gliding, gliding and then stationary camera. While Malcolm struggles to remember, Vincent is lost in despairing thoughts about his misery. The identical shot structure binds them, and their fates, tightly together, while other elements of the shots emphasise how they, like Cole and his mother in the dinner scene, each occupy totally isolated worlds.

I especially like the rhythm created by their alternating, brief dialogue lines, as if they are vocalists singing diametrically different versions of the same song. It should be said that the camera movements during these seconds are so discreet – as if fine-tuned into having an unconscious effect – that one really have to inspect the film quite closely to become aware of them. The general, consciously experienced intensity of the scene will also tend to drown them out. It is still good reason to believe that they will create a feeling of rhythm, coherence and contrast in the viewer’s mind. A similar, seductive rhythm can be very much felt in the alternating shots of Cole and Malcolm with moving camera, when the boy tries to run away from the psychologist in the scene of their first meeting.

Structural and meaningful echoes

The third article will explore a number of structuring elements of the film. But there are also quite a few scenes whose entire staging are creating more or less meaningful echoes, so it feels natural to bring this up in the mise-en-scène context of the present article. For example, both dinner scenes in the film are shot in long takes. Furthermore, the camera strategy of the restaurant scene, where it tracks in on Anna’s back and then turns around to show her face, is basically replicated in the post-funeral scene where Kyra’s father is given the box. The echo is reinforced by the fact that both scenes are slow, long-take situations and that both persons are sitting alone, have lost someone very close to them and are given something in the scene. Incidentally, there is also a very strange connection – too unlikely to be mere coincidence – in that both the box and Anna’s shawl on the chair seem to have the same colours.

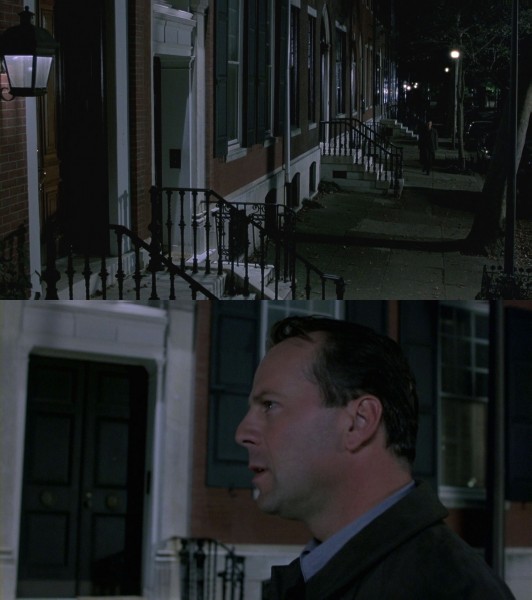

Even more telling is the harrowing camera movement inside Cole’s tent from the boy to Kyra’s ghost and then back to him again. Also this camera trajectory is repeated in the post-funeral scene, in Kyra’s bedroom when her ghost gives the videotape box to Cole. Furthermore, in both scenes where Malcolm is experiencing an emotional upheaval – when he hurries away from the antique shop after having broken its window, and when he arrives home to find Sean (Scott Fitzgerald), Anna’s suitor, coming out of the door of his house – the camera is moving towards him while he is simultaneously walking towards it. While the first scene is shot with an unsettlingly shaky camera, however, the second is tightly controlled and even elegant. Just look at how the camera is doing an expressive, slow dance around Malcolm at the end, before coming to rest, gazing meaningfully at the door. (This type of meaningful camera movement would be taken to great heights in Shyamalan’s next film, Unbreakable.)

The two other scenes in which Sean appears – the only ones where he has dialogue – are identically shaped. In the first one Malcolm sits working on Cole’s case in the cellar of his house, when Sean comes calling. In the second, Anna gives Sean a present in the antique shop. Both scenes start with a very long take, which is kicked off with a close-up of an object, respectively a psychology textbook and a ring being wrapped up. Except for the car accident scene near the end, these are the only scenes that follow this pattern. Curiously, the situations are also connected through the facts that Anna’s present to Sean is a book and that Malcolm makes a ring around a statement in his own book.

Many of the scenes where Cole’s mother is central – the breakfast scene (where she is introduced), when tidying up Cole’s room, and when she arrives home from hospital with Cole – are filmed with a supple hand-held camera, dominated by long, flowing takes. In addition, there is the fluid, long-take scene in the parking-lot where she starts to race with Cole sitting in a shopping cart. Among other things, the fluidity could be meant to indicate a possible past as a dancer – especially the start of the breakfast scene where, in deft movements, she is orchestrating various household chores – late in the film we learn about a traumatising incident involving a childhood dance recital.

There are echoes through succession: both scenes in the church are directly followed by situations where Malcolm is arriving at his house. The church scenes are also connected in another fashion: on the way there in the first scene, Malcolm is chasing Cole, gliding shots alternating between them, while the green area and the fence separate them. In the beginning of the second scene, the balance of power is radically changed. One floor higher up, Cole is now towering above Malcolm, but the structure of the alternating gliding shots remains the same and the banister has replaced the fence. (The choice of a catholic church, by the way, fits nicely with the film’s theme of secrets that eventually are confessed.)

There are also similarities in composition. The long, (mainly) stationary take of Anna and her two customers in the antique shop, framed by the big jewel showcase and with many objects in the foreground, is echoed in Kyra’s video tape of her puppet theatre (see below). Additionally, the antique shop scene has the tenor of a short, amusing play, and both situations depict unresolved male-female relationships and the tenuousness and inventiveness involved in handling them.

Twice in the film, we encounter an inventive way of overlaying voices from one scene upon another. During one session, Malcolm discusses how automatic writing could be used to explore Cole’s unconscious, and eventually, to eerie effect, their conversation is superimposed on a situation at a different time where Cole’s mother, soundlessly tidying, chances upon several pages of Cole’s “upset words”. More conventional perhaps, but with an even more unsettling and unreal effect, is the way the start of an intense discussion between Malcolm and Cole is laid over the short scene where Malcolm is hurrying away from the antique shop. The unruliness, both in sound and image, of Malcolm’s escape is in great contrast with the ultra-rigid continuation of the discussion.

Except for the second church scene, this is the only scene of the film based on the – in conventional films so ubiquitous – shot/reverse shot structure with the camera peering over the character’s shoulders. Shyamalan frames their faces much tighter than usual, however, which helps create a boxed-in and despairing atmosphere. The framing cutting off the top of the heads of the characters. Malcolm’s often unkempt forelock, which stands up in a cowlick that at times gives him a confused and slightly comical air, is now hidden, making his appearance even more gloomy. (Nevertheless, the form and mood of this scene seem strangely at odds with the rest of the film and one cannot escape the feeling that it is inserted mostly, and somewhat clumsily, to clarify and sharpen what’s at stake for the characters. It is also the only scene in which Osment’s acting seems strained.)

Unity and variety

We shall end this article with some scenes in The Sixth Sense that may seem simple and even conventional, but on closer inspection they have hidden resources of elegance and craft. The mind-reading game scene, where Malcolm tries to win Cole’s respect and confidence by showing how good he is at guessing Cole’s inner thoughts, consists almost entirely of point-of-view shots from both’s vantage points. That may not sound so impressive, but there are as many as 40 of them in succession, and they fit together like clockwork. There is a rhythm and fluidity in the editing and the matching of movement, and an eye for variation within an extremely limited framework, that creates a hypnotic fascination that for me makes the mind-reading game eternally fresh no matter how often it is viewed. It is impressive how the newcomer Shyamalan, of course magnificently assisted by cinematographer Tak Fujimoto and editor Andrew Mondshein, seems equally adept at long takes and precision editing.

Another favourite moment of the film is the short scene where Cole’s mother is studying photographs on the wall that seem to have been infected with mysterious white marks. (She wears the same headphones and clothes, so we can assume this is another part of already-mentioned situation where she finds the pages of Cole’s automatic writing when tidying.) It is only twelve shots and lasts 70 seconds, but a small masterpiece, again conjured up from very limited building blocks. The way her head moves when she looks at a new picture, in close-up with a camera that matches her movement in perfect vigilance. Her hand movements, with the almost ritualistic manner of her red fingernails touching pictures she looks at. The alternating shots of her face and point-of-view shots of the pictures. All of this create a hypnotic, almost dazed, experience of rhythm. There is also an indefinable sense of wonder of about the scene, in peculiar combination with the domestic setting, gently assisted by composer James Newton Howard‘s dreamy music. We only hear a faint humming of the music she is listening to in her headphones, as if a ghost of that music, underlining the eerie feeling of silence of the scene.

In the enchanting last shot, the camera gently rises behind her, each photograph seemingly a portal into some unfathomable mystery, all of them together forming some sort of ghostly galaxy, every element of the image brought together in a perfect visual composition. All of the scenes we have talked about so far are drenched in Shyamalan’s distinctive brand of methodicalness, but in this photograph scene he also displays a light and delicate touch. The same touch is also at work in the perfectly timed shot of the ghost of the traffic accident victim outside Cole and his mother’s car window, which in just a couple of seconds manages to be simultaneously shocking, tragically poetic and a poignant representation of the transitory nature of human life.

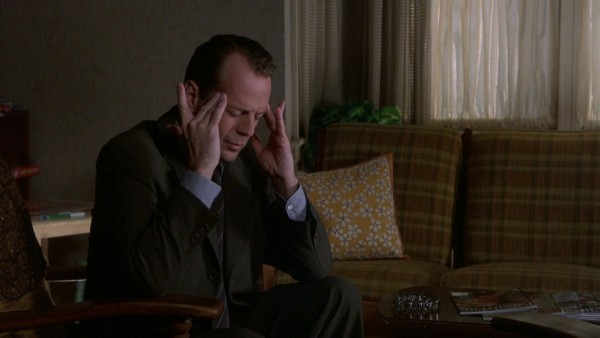

The last scene we shall go into here is the situation in the cellar when Malcolm finally becomes convinced that Cole is speaking the truth about his strange affliction. Again, the scene is minimalistic, even more drastically. With one exceptional exception, it is only Malcolm, a short flashback to Vincent Gray from the prologue, various shots of a tape recorder and one shot of an archive box. The scene lasts 3 minutes and 14 seconds and as much as 73% of the time is devoted to close-ups of Malcolm. In one case the camera lingers on his face for an “eternal pause” of 40 seconds while he is sitting in silence, waiting for some sound to turn up on the tape he is playing – clearly not your usual Hollywood film!

But in the magical moment when he finally starts to realise how everything hangs together, everything changes. We would have expected to see his face in this breakthrough moment, but paradoxically, and highly inventively, we now see him from behind while the camera slowly tracks in on him. At the same time, we can see his surroundings in a coherent view for the first time of the scene. It is as if a lot of elements we, the viewers, have seen throughout the film – the wine rack, the stone walls, the table, the chair, books and boxes, as well as the important motifs of arcs (above the wine rack) and lamps – now come together, in a visual representation of Malcolm’s experience of how the pieces of the puzzle suddenly fit together. The fact that we are denied the look on his face and have to do with his back, only reinforces the glorious mystery of the moment.

M. Night Shyamalan‘s scenes may not be on the autonomous level as Kubrick’s non-submersible units – major plot points that entire segments of his films were built around. But they have an air of being short films – each with a distinct formal idea and honed to perfection as stand-alone units – while still fitting snugly within the larger frame of the film. This is not as fully developed in The Sixth Sense but will become even more pronounced in the next three films in the series, before it recedes somewhat in the more “free-form” Lady in the Water.

Almost perfect

After singing the praises of The Sixth Sense, I can now offer some criticism in these closing words. We have already mentioned the slight awkwardness of the intense discussion scene between Cole and Malcolm. There is another scene that does not work at all, however many times I see the film, namely the situation where Cole is brought to the paediatrics clinic after his breakdown. This is Shyamalan’s cameo scene, but he is absolutely fine as the suspicious and faintly menacing doctor. But the idea of shooting the entire scene through a bewildering collection of many-coloured hoops and spirals – probably toys for the young patients – is an exceedingly silly idea. It totally undermines the seriousness of the scene, and represents a very strange misstep for a director who in the rest of the movie shows such an astonishingly assured judgement. (In the third article, however, when discussing the motif of ancientness/modernity, I cautiously propose a justification for the scene’s strange visuality.)

Furthermore, the long scene in the antique shop where Anna is trying to sell a ring to a rather childish Indian couple, seemed on first viewings strangely unconnected to the rest of film. That scene has greatly appreciated in value, however, because of its visual elegance, charming naivistic humour, the screen time it allows the otherwise underdeveloped character of Anna, and not least, the richness provided by the long take’s parallel display of the characters’ diverse personalities, moods and motivations. Additionally, it is paving the way for the important part the wedding ring will play in the ending. (We return to this in the second article.)

I solemnly promise that this will be the last criticism to pass my lips about The Sixth Sense. Absolute flawlessness is not a requirement for a film to be a masterpiece. In the next two articles we shall explore further evidence that M. Night Shyamalan‘s breakthrough work deserves such a status.