Unbreakable, Part I: Characters and relationships

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the first article about Unbreakable. The second is here, the third here. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

These three articles are the result of a close reading of M. Night Shyamalan‘s 2000 film Unbreakable. In this first article I will start out with some general considerations about the film. The rest of the article is devoted to a discussion of the film’s characters and relationships. It starts with its two most important characters, Elijah Price and David Dunn. Then it continues with the interactions and interconnections between David and his family, between David and Elijah and David and The Orange Man. There are two addenda: a list of the amazingly high number of similarities between Unbreakable and The Sixth Sense, and a list of errors in Unbreakable.

Throughout there will some summarisation of theme, plot or other quite obvious features of the film, to provide a foundation for the discussion. But the main focus here – in all four articles – is the finer details of the film, with an emphasis on how various elements of the film interconnect. I will always try to suggest how the details could reflect the film’s meaning.

The second article explores the film’s motifs: high and low culture, numbers, the visual motifs of arches and staircases, as well as two scenes: the train scene and a scene mysteriously obsessed with orange juice. It will also explore the use of colour as motifs. The third article explores the film’s highly distinctive visual style.

In order to discuss the film properly, I will eventually have to reveal the whole plot, including the major plot twist at the end, for both Unbreakable and The Sixth Sense.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of Unbreakable, here is a brief outline of the plot.

Preview

First of all, however, let us take a brief look at some of the above-mentioned finer details, using pictorial material from all around the four articles. The purpose is to get across the unusual depth of detail in this film, and also to ponder whether they might be intentional or not. (Not that unintentional coincidences cannot be interesting, of course.)

Please be aware of the option to click on the frame grabs to enlarge them. Clicking on them yet again will enlarge them even further.

Purple (and blue) is heavily associated with Elijah throughout the film, so it seems like a very subtle touch to give him a purple aura. Most probably this is simply an optical error, a chromatic aberration, but considering how it fits with the film’s general colour scheme, one would think this is a mistake that Shyamalan has welcomed. There can be no doubt, however, that the indoor shot has been specifically set up to achieve that coloured lighting effect. In both scenes Elijah tries to convince David that the latter has superpowers, so it is only logical in terms of motif that Elijah’s purple colour should “infect” David by shining on him, especially now, since the phone message is a key moment in Elijah’s campaign of persuasion. (In keeping with this, there is also a purple line along David’s neck in the stadium shot.) Considering how faint that coloured light is, it says something about the level of subtlety on which Shyamalan operates in this film. So if we really want to properly understand Unbreakable, we ignore its many small details at our peril. Unbreakable is indeed a “world that has to be watched very carefully,” to paraphrase the famous line from Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943).

Moving on, Shyamalan’s employment of “short-term foreshadowing” feels original. This is a device that presents clues about what will immediately happen – tiny, “invisible” versions of the obvious, heavily telegraphed clue of Elijah’s glass cane breaking into bits against the subway stairs seconds before he is injured himself. So what to make of the situation below from the epilogue? In a pause in the conversation between David and Elijah’s mother they turn to look at Elijah. As the focus shifts from the foreground to the background, Elijah raises his right hand. He keeps it in the air until, after several seconds, the focus shifts back to the foreground again, which “causes” him to lower his hand. During the rest of the scene, as we see him out-of-focus in the background, that hand remains virtually motionless. This stylised use of the hand, perfectly timed with the focus, seems to be more than mere coincidence, since in a few seconds that same hand will be pivotal in the film’s most momentous turning point:

More foreshadowing: When David arrives at the railway yard to inspect the wrecked train cars, there is a sign hanging upside down. The scene triggers a flashback, where David as a young man rescues his then-girlfriend Audrey from a car that is… upside down:

Earlier in the film, this upside-down motif was further involved through the news clipping of the car accident. In this scene, that clipping is joined by another one, of the train accident. The combined presence of those two clippings foreshadows the pivotal connection he is later to make between the two accidents: that he escaped unhurt from both of them. (All this is fully discussed further down in this article, here, and the upside-down motif, manifested both in objects within the shot and in the shot itself, is explored in the third article.)

We shall end this preview with a little joke. At the end of the stadium sequence, Elijah falls on the subway stairs after having chased a gunman. The blue door in the first shot of the sequence (as we saw further up) serves as some kind of starting signal, tipping us off, however so subtly, to the fact that this colour will be present is almost every shot of the entire sequence. Thus, as Elijah lies on the stairs with a lot of broken bones in the last shot, it is only fitting that we see some blue from his coat’s inner lining stick out:

Not only is the joke perfectly hidden since such signs so naturally occur in our everyday lives that it is difficult to make an interpretational connection (and the bus is moving when the shot starts, making it even more difficult). But the connection is much more specific than merely alluding to broken bones, since (more foreshadowing!) Elijah will in fact spend the rest of the film in a wheelchair…

A comparison of two films…

Is Unbreakable better or worse than The Sixth Sense? It is a difficult comparison since Unbreakable speaks in such a different voice. The Sixth Sense is more direct, both in storytelling and evoking emotion. The vivid, “artlessly” engaging performances of Haley Joel Osment and Toni Collette have no equivalent in Unbreakable. In a more subdued register, however, the role of David Dunn may be Bruce Willis‘s best performance. (It can only be rivalled by his role in Terry Gilliam‘s 1995 masterpiece Twelve Monkeys). Through a relentless regime of internalised acting, the wise-cracking action hero here reveals himself to be perfectly suited to portray depression. Samuel L. Jackson‘s Elijah is one of his most distinctive roles, however built around outer flamboyance rather than inner depth. Very solid support is given by Robin Wright Penn as the calm, mature and warm-voiced Audrey, and by Spencer Treat Clark as the emotionally troubled Joseph, the latter continuing Shyamalan’s line of impressive child acting that will conclude with Signs.

The scene in the train station where David allows himself to be swept up by his own superpowers combines down-to-earth urgency and majestic grandeur in original fashion. The sequence where he enters a house to take on The Orange Man, the home invader, instils a hellish feeling of slow-burning dread and perversion. The chase scene with Elijah and the gunman is brilliantly executed, and Elijah breaking his bones on the subway stairs must be one of the most brutal sound effects ever in cinema. Shyamalan’s trademark methodicalness is drilled into every moment. The weightlifting scene has an elegance and virtuoso precision that rivals anything in The Sixth Sense.

Still, on the level of immediate impact, it cannot be denied that the former film does have a higher number of stand-out scenes – and perhaps also fewer false notes. On the other hand, the one scene in Unbreakable that initially strains credulity, where Joseph threatens to shoot his father to prove that he is invulnerable and therefore a superhero, is perfectly fine when one considers how devastated the boy was in the scene just before – over the injustice of his father reverting to denial of his already-proven powers, thereby robbing Joseph of the father figure he so desperately needs. The only false notes in the scene (perhaps the only major one in the entire film) is Penn’s unconvincing acting towards the end, and Shyamalan’s unsuccessful attempt to inject absurd humour at one point (“N-no shooting friends, Joseph”). Incidentally, despite Unbreakable‘s pervasively bleak atmosphere, there are a surprising number of small humorous touches (at my count, twelve overt ones, all successful except the above-mentioned), most of all in the weightlifting scene.

In style and formal approach, Unbreakable is radically more adventurous and consistently bold. Unbreakable initially seems the simpler film but it is a deceptive simplicity – once one starts to become aware of, for example, all the hidden echoes and connections between characters, or (especially) the use of colour, a Pandora’s box springs open. Even though the analysis of both films is probably far from exhausted, as an analytical object Unbreakable seems the most complex. Being much more concerned with mood and less with event-driven storytelling appears to leave it more opportunity for symbolism and subtlety. Furthermore, the film music in Unbreakable is more complex and engages with themes and visuals in a more meaningful way. The importance of the colour red in The Sixth Sense is developed into a highly intricate colour coding in Unbreakable, which will be described in detail in the second article.

The cascading closures of The Sixth Sense are more beautiful and extensive. Its final twist is by far the most satisfying and rich. But here one has to consider that the Unbreakable twist has a completely different goal. It does not want to create closure at all, but rather the opposite: to pull the rug from under the hero, and the audience, in a strike of poetic irony, to crush a rediscovered belief in a rational, orderly world. (There is closure for Elijah, however, for whom everything now makes perfect sense.) This is of course not as fulfilling emotionally, but not necessarily of less artistic quality. Furthermore, at the more local level of memorable key lines, Unbreakable‘s “I think this is where we shake hands” has a chilly surprise and ominousness that rivals the former film’s famous “I see dead people”, although it was unable to achieve as iconic a status.

In conclusion, I prefer The Sixth Sense for the precision-point storytelling and the emotional experience, but Unbreakable has a mesmerising pull all of its own, and letting oneself succumb to the flow of its mood, style and enigmatic formalism is a quite delicious experience.

…which are in reality the same film

“This is an art gallery, my friend, and this is a piece of art.”

This is Elijah’s stern rebuke to a customer who wants to buy comic book original art for his four-year-old. Elijah’s project is to elevate the low-cultural art form of comics to fine art. But this could be taken as emblematic of Shyamalan’s project with Unbreakable as well: it is as if he wants to “elevate” the wildly popular, relatively straightforward The Sixth Sense to the level of a European art film, and introduce this film-making concept to the same mass-market audience that embraced the earlier film.

Unbreakable is, if not an outright remake, a re-imagining of The Sixth Sense. The kinship of the two works has been noted by many, and this addendum lists a vast number of similarities. The same basic thematic material and plot structure is transformed into a mood piece and a formalist project. The result is the only mass-market, mainstream Hollywood film I can think of that is a decidedly formalist film. Virtually every shot is done with a stylised approach. With some Brian De Palma-like touches thrown in (the pirouetting camera in the hospital reception scene springs to mind), Unbreakable is at times a superhero film as if filmed by Tarkovsky, or perhaps even more apt, a Béla Tarr with more tolerance for cutting. (The Hungarian inspired at least one other contemporary American director, Gus Van Sant, whose 2002-2005 triptych Gerry, Elephant and Last Days are, by own admission, heavily inspired by him.)

The film’s cinematographer Eduardo Serra observes in this interview [but be warned that some scenes are inaccurately described in it]:

I must say that working with Night was a fascinating and wonderful experience. He doesn’t work in the traditional, classic American way of shooting a master shot and then doing plenty of closer shots just in case. He doesn’t really do coverage; he has very long, composed shots, and everything is carefully storyboarded. Although we certainly changed [some] things, most of the time we followed the storyboard. His approach combines the best of both worlds: America and Europe. Night has the style and freedom of imagination that European directors are allowed, but at the same time he’s not self-indulgent and is always focused on the audience, which European directors often tend to forget about.

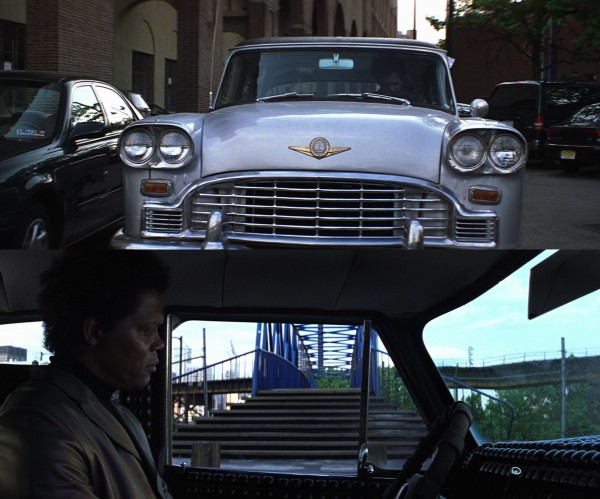

The glacial pace and somber mood are of course not just arbitrarily applied to the film, for this reflects the hero’s emotional numbness and bleakness. For a mainstream Hollywood film, there is remarkably little action. The first suspense occurs approx. 41 minutes into the film, with the chase sequence with Elijah and the gunman. (Note the authority by which the pace of the film “shifts gear” through the suddenly brisk cutting in the first seconds of that sequence, when Elijah sits in the car.) Nothing much has really happened until then – it has all been mood and hushed conversations – and the train accident, which ought to have been a spectacular way to grab the audience by their throats at an early moment, is emphatically not shown. Instead viewers are soon treated to an unbelievably static shot, lasting more than two minutes, when David wakes up in the emergency ward. (The third article will discuss the film’s long takes and average shot length – which is 18.9 seconds, in the same range as Antonioni classics like L’avventura and The Passenger.)

Even though The Sixth Sense, through its calmness and serenity, had been quite unconventional, it still broadly conformed to audience expectations for a gripping night at the movies. But already in Unbreakable Shyamalan starts to push the Hollywood envelope in a major way. Except for Signs – although he could not resist sprinkling that with quirky elements – the last four of the five-film series under examination here at Montages see him starting to take the standard contract of communication with the audience lighter and lighter. The general moviegoer began to feel cheated, something that together with a decline in his later films’ quality, contributed to Shyamalan’s horrendously low esteem today.

Another challenging aspect has to do with mood. In Unbreakable, it is as if the entire human condition has reached a dead end. The hero is apathetic and seems as alienated in his own home as in the crime scene house he enters towards the end. The gulf between virtually every character seems vast. Even minor characters move through their world as if they were ghosts from The Sixth Sense. In its almost uniform oppressiveness and bleak worldview, the only other major Hollywood film that could match it must be Se7en (1995), which also has a similar slow pacing. But David Fincher‘s film, however brilliantly executed, is much more conventional in form and much less subtle. In Unbreakable, there is no serial killer to forcefully articulate the film’s themes.

Furthermore, while in most Hollywood films the final showdown is supposed to be exciting and cathartic through violence, Unbreakable‘s battle between David and The Orange Man there is no triumph or payback – instead it plays out like a sad medtation of the violent nature of mankind. (Another big difference from Se7en, whose climax is extraordinarily intense.)

In Unbreakable, it is not only that the pace is slow. The subtle, gradual revelation of important elements, for example the degree of the hero’s alienation from his wife and child, is familiar from European films that demand a high level of active participation from the audience. The camera movements – all of them seemingly pregnant with meaning – are often serene and executed with grace and majesty. On an unconscious level, the film is criss-crossed with chains of motifs and prefigurations, including his employment of “short-term foreshadowing” (as we touched upon here).

Unbreakable is executed in an extremely confident and authoritative manner. The film’s construction is less well hidden, probably intentionally, than in The Sixth Sense, however. One has a nagging suspicion, though, that Unbreakable is so thought through and deliberate that it risks becoming too studied in some scenes – there may be a slight pretentiousness creeping in, in that some of the most stylised formal devices might not always co-operate perfectly with the thematic meaning of the scene. (For example, perhaps, the scene in the comics gallery as he rejects Elijah for the third time, where the camera tracks away from David until he almost disappears from the shot.) Anyway, more than in any other Shyamalan film, one feels that he is discussing cinematic form and what it can be used for, in a way not dissimilar to Brian De Palma.

As for the themes of Unbreakable, it is standard Shyamalan terrain: finding one’s purpose, mentor characters, denial, withdrawal from life, the moral squalor of modern America, for example through the coldness between the characters and the film’s series of visions of sordid crimes. (I discuss his general themes here.) There is a neat and quite discreet structural device informing the plot, however: there are a large number of scenes where one character is persuading another to do something. (On the train, Davids starts persuading the young woman to have a fling with him, Elijah’s mother persuades Elijah to leave his room, Elijah and Joseph constantly try to persuade David that he is a superhero, Audrey and Joseph try to persuade him not to leave them, the clerk tries to persuade Elijah to leave the comic book store, and so on.)

Finally, a few words about realism. Unbreakable strives for this in two areas: its characters’ emotions and grounding the story in a realistically depicted everyday world (as usual with well-known Philadelphia locations). The story itself is clearly a fable. There is no attempt to give even a pseudo-scientific explanation for the physical impossibility of superhero powers. The fact that David has never become aware of his resistance to illness, his superhuman strength (never even getting a scratch) can be explained away by his state of denial, but it is strange that nobody else, especially in his football-playing days, has noticed. Some scenes are flagrantly implausible. When David wakes up after the train accident, his invulnerability seems to have protected his clothes as well, which are not at all torn. The epilogue is the “worst”: Elijah has bomb-making equipment lying around in his inner office, although there is an exhibition just a few metres away, and spectators could saunter in through the open corridor at any time. With all these people around – including a policeman! – Elijah even shouts after David about his super-villain status.

Elijah Price: egocentric man-child

Except for the last crucial scene, the only empathic emotion Elijah Price shows in the film is a measure of warmth for David when he finally steps out of denial to accept his superpowers. After Elijah has revealed that the three terrible accidents in or around Philadelphia were engineered by him to smoke out a “sole survivor”, Elijah becomes highly emotional, however. The last shot of the film shows him with eyes welling with tears. But his line just before, “So many sacrifices – just to find you,” is unlikely to be about the victims of his terrorism – for example, the wording connects directly to the earlier line, “There were so many times I questioned myself.” No, he cries over his own sacrifices in the long struggle to prove that there was indeed “someone else – the opposite of me at the other end” of the spectrum. Like the Norwegian mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik so tellingly showed during his trial, Elijah has become a psychopath who can only feel emotion about himself. His warmth toward David, too, was in reality about himself, since David functions as a physical extension of Elijah. (In the second article, we will see how the use of colour and music allows Elijah to join “in spirit” David’s adventure with the Orange Man.)

That last shot (above) is a close-up of Elijah from a camera position similar to one that, before the revelation, served as David’s point-of-view of Elijah. But now David has turned his back on him and left. There is no one at the other end any more, and this subtly increases our perception of Elijah’s aloneness. But not that Elijah cares at this point. He is totally lost in ruminations. His egocentric world-view has no room for other people any more, there is no hope for him to remain human. While David started the film in a state of distancing himself from everyone and ended up embracing them, Elijah’s trajectory has also in this respect proved him to be David’s exact opposite.

When reflections are mentioned in writings about Unbreakable, it is often in a general way, but they are in fact restricted to the early parts of the film. Metaphorically they indicate that Elijah is as fragile as these breakable reflective surfaces, but they also appear for a very specific reason. Each of Elijah’s three time planes are kicked off by reflections, which also show a trend of depopulation and dehumanisation. Birth: the mirror of the prologue is full of people and his mother is visually dominant. Age 13: the TV screen shows Elijah and his mother as lonely, distorted figures, and she is now diminished in stature. Grown-up: the display glass casing is dominated by the piece of comic book art, with the humans, Elijah and the customer, even more ephemeral and relegated to the sidelines of the frame. Furthermore, the grown-up Elijah is shown as relentlessly eccentric and apart, for example through his clothes. This is in contrast to the time plane as a 13-year-old, where he, even though an outcast, is still shown to be part of the black community in West Philadelphia. This is suggested by the fact that the clothes of the kids in the playground, and even passers-by, use exactly the same colour scheme as Elijah and his mother.

Elijah is allowed the film’s last words: “I should’ve known way back when. You know why, David? Because of the kids. They called me Mr. Glass.” (A typical super-villain name.) In addition to the closure this achieves by connecting way back to his second utterance in the film, there is another closure in the fact that Elijah has now become able to speak with some magnanimity of those who hounded him in childhood. The middle stage of this development arc comes almost exactly at the film’s midpoint (end titles subtracted). Here he is in hospital after having fallen down the subway stairs, when he again mentions “Mr. Glass” and the kids, now with neutrality.

We shall return to how Unbreakable is drenched in childhood traumas. Locally in Elijah’s character, however, it is curious how the child seems to co-exist with the cultured grown-up. Evidently, the taunting of the kids seems very much to remain with him. (He also talks about children with the same disdain and scorn as about love.) Furthermore, his reinvention of both himself as a connoisseur of art and comic books as refined culture, has made him chase down the original cover art for the first comic book of his childhood. These internal contradictions come surging to the surface in his rage when he realises that his customer intends to buy it for a four-year-old. It also seems paradoxical that he lavishes lofty explanations on drawings that seem like rather trite and traditional superhero artwork.

Later, after David has rejected him for a third time, Elijah takes it so badly that he forsakes his tasteful gallery for a gaudy comic book shop – like an alcoholic aristocrat seeking refuge in a seedy bar to demean himself. (Ironically, at this point David and Audrey are having a drink in a bar, but a very posh one.) But like alcoholics sometimes, Elijah cannot get drunk, only depressed, and regresses to the level of a shamelessly obnoxious child when the clerk tries to get him out. One of the subtler indicators of his man-child nature is the fact that when his time plane as a 13-year-old dissolves (thereby tightly connects it) to the sales scene in the gallery of his grown-up plane, he is still wearing a similar type of polo neck sweater, in both cases also worn inside an outer garment.

Now for a subtle example of the extensive interlacing of past and present in Unbreakable. Who would have believed that there is a marked similarity between the stationary nature of Elijah’s 13-year-old time plane and the dynamism and excitement of the sequence where the adult Elijah is chasing after the gunman? The film music is a clue. When Elijah sits in his car the exact same music is playing (five repetitions of a four-note motif, with its last note omitted in the last iteration), albeit a bit faster, as when the young Elijah sat before the blank TV screen. Shyamalan even takes care to show Elijah sitting frozen in despair for a moment (David has just rejected him) to connect back to the 13-year-old’s depressed stupor. The car compartment is an equivalent to the apartment, the car’s padded upholstery emphasising the safety of this environment as well. At the exact same spot in the music as in the past, when his mother entered the room, Elijah becomes aware of the gunman walking past the car.

Later, when Elijah is standing at the top of the subway stairs, looking down on the dangerous descent, this is similar to Elijah looking down at the gift on the bench from the height of the second-floor apartment. When Elijah falls down the stairs, the film music plays a sad and fateful rendering of the same theme as when Elijah sat on the bench admiring his comic book. (The musical echo is here obvious, in contrast to the subtlety of the other echoes between these segments.)

Both segments started with sadness. Then Elijah engaged with life outside his sadness. The intrusion of another person caused him to leave a position of safety, respectively to get the gift on the bench and the “gift” of confirming David’s superhuman ability by finding out if the man really had a gun. But the last time, instead of the simplicity of just being fascinated with the comic book, that fascination has led to something very complex – great grief but also great joy (the latter because he is able to get a glimpse of the gun).

Finally, the film’s epilogue echoes the prologue, in that both feature Elijah’s mother, who has been absent for the entirety of his grown-up time plane. Like a ghost from the past, there is something spooky about her sudden reappearance, a hint of something sinister beneath her outward friendliness. Most of all this is indicated by her large eyes while explaining, “See the villain’s eyes? They’re larger than the other characters’. They insinuate a slightly skewed perspective on how they see the world – just off normal.” Her perfect imitation of Elijah’s way of speaking about comic books is also unsettling, yet easily explained by her function of being his saleas assistant. There is an unresolved residue of suspicion, however, that she may have been more instrumental in Elijah’s dubious development than is let on. (This conversation also foreshadows, of course, the revelation of Elijah being a villain.)

David Dunn: selfless man cloaked in denial

David Dunn’s dazed look on the train in his first scene tells it all. Later, his brittle look – his profound depression now overlaid by the shock/guilt of being the sole survivor of the train wreck – on the staircase during his first conversation with Audrey makes him look anything else than “unbreakable”. David is in denial. He has implanted himself, so to speak, with false memories. He has forgotten about his childhood accident, that he has never been sick, that he faked the knee injury that ended his football career.

This has led to a years-long depression. During the film, whenever he starts to entertain the thought that Elijah might be right, even after he has weight-lifted more than humanly possible, he eagerly embraces every setback, as confirmation that he is after all a nobody. This self-hate is what makes him distance himself from Audrey and Joseph, and it seems especially important to David that his son must not admire him.

During their attempted reconciliation in the bar, David admits to Audrey that he knowingly keeps his family at a distance. Early in the film, three short scenes in succession prove that this distance is also extended to the rest of the world, indicating how his self-hate and unassertive appearance lead others to treat him like a nobody. We shall return to the silent scene at the end of this chapter, but the two dialogue scenes are shot with a strident staging in depth, giving a physical measure of the gulf between him and others. The elderly secretary does not even look up during their conversation, and his boss’ brusque tone has more than a hint of contempt (“What, you hit your head on that train? Get your brain to start working again?”).

In prefiguration of his coming superhero persona, the only time David shows some assertiveness is when performing his work as a security guard. Other than that, he is a selfless man surrounded by selfishness and indifference, a sub-theme of the film. Like Elijah could only think of his own sacrifices in the epilogue, David’s involvement in the train accident raises no empathy in the secretary – only a memory of an accident she herself was in once, in which a horse was even killed in punishment for almost trampling her to death. David’s boss automatically interprets David’s question (how many sick days he has ever taken) as a sly request for a raise, and rewards David’s “selfishness” by granting it. Later in the film, the babysitter reacts to the news of a possible relocation of the Dunn family, or even the misfortune of a marital split, only in terms of what it will mean to herself.

One wonders whether David might have a mother issue. A major (and very sweet) point is made in the film about his need to be reassured by Audrey each time he has had a nightmare, as if he were a small kid. On this issue, both the secretary and her story foreshadow another elderly mother figure – the school nurse who has her own story from the past to tell. This story strikes unpleasantly closer to home, however, for it is about David. His deference to these ladies is noteworthy. In the first scene, he is standing with his cap in his hand, a politeness not out of place, but the expression “hat in hand” springs to mind, suggesting a somewhat exaggerated humility. In the second scene, when David is about to leave, he moves his cap to a visible position in the shot. The thematic mise-en-scène purpose of this seems to be to keep it visible in the lower part of the shot for quite a while (see below), as the nurse starts to tells the story and the camera tracks in on David. All the while David has a peculiarly nervous and cowed look, and his question just before, “Do I need to put any smelly ointment on him [Joseph] or anything?” has a silly, childish ring to it. In fact he may unconsciously recall the nurse from when he was a small boy at the same school, which would add to his sense of intimidation. The nurse, who seemed friendly enough in the beginning, now adopts the other characters’ slightly contemptuous tone. The facts that she likens the story to a “ghost story” and that we cannot see her face at all through this long take, add to the creepiness of the situation. (In the next scene with David and Joseph in the playground, the “hat in hand” device is continued – even though it is very sunny, the completely dejected David does not put his cap on.)

Later, during David’s struggle with The Orange Man, the childhood drowning of the story is re-enacted, with The Orange Man acting the part of a school bully. There is, however, an interesting touch here that mirrors the positive trend in David’s life, for the fact that he is saved by two children reverses the roles of the childhood incident, when “two skinny little kids” made David drown. (There is another echo here, since Joseph, too, tried to stop a bullying incident, that too with two perpetrators: “It was Potter and another guy. They were messing with this Chinese girl in the dressing room”.)

David’s encounters with the secretary and his boss book-end a scene where David is watching football players at practice. It is quite short, just 29 seconds and four shots, but pregnant with meaning – especially echoes and foreshadowing, something that Shyamalan seems concerned with to the point of obsession. Let us dwell on this scene for a moment before we return to these methods in the second article.

- The scene is an efficient yet poignant encapsulation of how the passive David has become an on-looker at his own life, since his real self should be out there on the field. Instead, he has doomed himself to be a security guard on the sidelines, literally speaking, as he says to Elijah, with double meaning, “I gotta be down on the sidelines during the game.” The first shot shows him like a ghost, without features, constricted by the sides of the entrance.

- This is the only scene with rain until the film’s last quarter, which in contrast is soaked in water. By containing both water and football, it invokes his first two accidents and central ingredients of his tragedy, his childhood drowning (which also foreshadows his weakness as a superhero) and the car crash that ended his football career.

- It briefly introduces the raincoat that will be his “superhero outfit” in his clash with The Orange Man.

- The coat, part of his security guard uniform, invites comparison with the uniforms of the football players and the coat’s “split personality” reflects David’s own situation. At the moment, its ordinariness compares disfavourably with the powerful-looking football outfits. But the future potential the coat represents means that David with his super-strength will easily outclass them. Right now, the scene emphasises David’s weakness and helplessness when watching the football players.

- His cap (visible under the hood) shares the colour of the player’s helmets but its softness is another indicator of his weakness compared to their hard helmets. The rain adds even further emphasis, since water will be established as his lone weakness – his Kryptonite – as a superhero.

- The shots of the athletes are dominated by one player. He represents the object of David’s identification/envy, further emphasised by his and David’s centralised position in the shots. But there is also another player who is quite prominent. The fact that they have the same number (31) can be said to symbolise David’s inner split and also his sense of being overpowered (two against one).

- These two players are on different teams. They are opposites, but the identical numbers nevertheless make them the same – a situation is reminiscent of David’s and Elijah’s relationship.

- His distance to them underscores the impossibility of his ever joining them because of the self-imposed exile of his “knee injury”.

- The concluding close-up of him under the raincoat hood (shot 4 above) connects forward to a similar close-up that will conclude the scene that launches a flashback, which will make him realise that this injury was fake.

- The film music accentuates the wistful, pining nature of his gaze.

- All the players’ numbers are more food for the numbers motif discussed in the second article.

- Finally, this is the first scene that, through the composition of shot 1 above, establishes in earnest the arch motif (discussed in the second article) that will soon permeate the film. (Until now only seen discreetly in the church and in David’s home.) Also note that the main player has received the ball in shot 3 framed by a far-away arch, similar to the one above David.

Upon the first viewing, very few of these meanings will be present other than, at best, a faint murmur. But when one gets to know the film well, this short scene will become a kind of symbolic nexus, radiating meaning on a variety of levels, across the entire film.

David, Audrey and Joseph: family at a distance

In milder form, David and Audrey repeat the pattern of David and Elijah being on opposite ends of the spectrum. It is worth noting that the news clipping about the car accident states Audrey’s maiden name to be Inverso (possibly inspired by Gino Inverso, who played the child version of Vincent Grey in The Sixth Sense). Football being a highly physical sport, Audrey, whose job is healing and health care, on principle “don’t want violence in my life”. Even though their relationship is wholly resolved at the end, it is ironic that on one single issue David will go on to deceive Audrey – literally going behind her back in the last kitchen scene – and keep his superpowers from her. In addition to adhering to the superhero trope of a secret identity, one probable reason is that David in fact killed The Orange Man – a controversial decision by Shyamalan, to put it mildly, because it did not seem necessary – the actual scene is quite vague about it, but the newspaper story reveals it.

Clearly, David and Audrey had problems communicating. As if in reflection of this, in virtually all dialogue scenes – David on the stairs right after the accident, the two situations where they each come to talk to the other in the middle of the night, and at home after the bar scene – the communication is almost strictly one-way. Only the bar scene itself contains a genuine exchange, tellingly at a stage where David’s mind has started to slide towards healing, by accepting Elijah’s superpower idea.

The bar scene is important for the characters’ development, but other than that their relationship revolves around three pivotal, almost wholly wordless scenes. The first scene is the dreamlike situation in the hospital reception area just after the accident, where major aspects of the film are introduced in a subtle fashion more akin to a European art film than a Hollywood movie. Even after such a disaster, their greeting is extremely hesitant and Joseph, desperate to use this to save their marriage, clasps their hands together. They let go very soon, however – it is difficult to tell but apparently it is David who breaks it off.

The second scene is the car accident flashback that makes David realise that he had faked his knee injury. Why? Here some have questioned the psychological believability of the film. In any case, we are talking about a fictional character in a story that aims to make a point, not about real persons bound by everyday believability. Still, as we soon shall see, in the context of the film his decision is not as far-fetched as it may seem.

In the flashback several of the film’s strands converge. It is fruitful to consider two other scenes, one prefiguring the flashback and the one leading to it. In the prefiguration scene David is looking at newspaper clippings of his football career and the car accident (here). The scene is telling in several ways. The presence of the gun and the fact that David does not find it in its usual place foreshadows the kitchen confrontation scene with Joseph. The fact that David is standing in a closet while reading is a visual metaphor for how the car accident has constricted his life. Most important to us right now, however, is the fact that while he is reading, Shyamalan chooses precisely this moment for Audrey to knock on the door. She says, “…it’s a big deal that you walked away from that train. I feel like it’s a second chance.”

The scene leading to the flashback shows David gazing at the remains of the train accident, a collection of wrecked railway cars. His thoughts might be dwelling on the woman he tried to seduce and the little girl, who both died with all the others. These memories make him think of his past, connecting the train and car accidents. In both cases David is left completely unhurt. In the past, Audrey is stuck in the car, threatened by a fire. (Incidentally, the fire here being Audrey’s “weakness” creates a nice opposition to water being David’s weakness.) Without having discovered his superpowers yet – in his football career he was a quarterback, a role depending less on physical strength – in desperation, he uses his strength to rip the car door open. (This action was foreshadowed when David broke open the door of the railway hall in the previous scene.) He succeeds in getting Audrey out.

When Audrey comes to she says, “I thought I was dead,” and David responds, “Me too.” David’s answer has double meaning: he may also think back to his almost-drowning as a child. So in a way, David may now experience a powerful bond with her, since both, in a certain sense, have woken up from the dead. Furthermore, it is quite plausible that David feels guilty about the accident. Audrey was sitting in the passenger seat, so David must have been the driver. There are no other cars around to blame, so David may feel responsible for the car sliding on the black ice.

To summarise, a lot of factors come together to influence his decision:

- the bond of he too having “died”

- guilt over having been “responsible” for the accident

- an unconscious knowledge of his own invulnerability may have led to him to take greater chances in the icy conditions than he should have, and on some level he acknowledges that

- Audrey looks at him with a strangely pleading expression, as if she needs him desperately

- like Audrey wanted to give their marriage a second chance after David walked away from the train accident, David may want to give the relationship a second chance

- in his overwrought state, he exaggerates Audrey’s aversion towards football and uses her broken leg as inspiration to fake an injury.

The third pivotal scene occurs when David comes home after having fought The Orange Man. Like a superhero costume after mission accomplished, he hangs up the raincoat in the cupboard. In an echo of David touching people to find criminals and also of their hesitant touch in the hospital reception area, his coat touches his wife’s yellow jacket. To link it exclusively to the hospital scene, we have not seen the jacket since. The touching of their clothes foreshadows David’s decision, or simply gives him the idea, of getting reconciled with his wife. The symbolism of the image is further emphasised formally: the camera gently, invisibly, tracks in on the clothes (a Shyamalan trademark in Unbreakable) and the shot dissolves into the next one.

Here, re-enacting the aftermath of the car accident, David is carrying Audrey up the staircase that in several scenes so far, for example here (the film’s staircase motif will be discussed in full in the second article), has symbolised their separation. (The motif of his super-strength is carefully transplanted into this scene through the effortlessness of his carrying.) Like in the flashback, Audrey is initially lying “lifeless”, but in another echo she then opens her eyes. But the pleading look of the girl of the flashback is now replaced by a mature woman’s gaze, completely at ease, open and honest. Echoes to both the flashback and hospital scene are created by the scene being shot in one long take, and another echo with the hospital scene by movement: at the hospital, the camera formed a pirouette around David, but now David himself is making a pirouette, with Audrey in his arms. While the first pirouette was disorienting, now David himself is in command of the movement; he is the active part because he has been healed and through his own effort.

The camera follows them up the stairs. He puts her on the bed, and then joins her. They lie closely together, like the clothes in the cupboard. All through the scene they are bathed in yellow-green light, fusing the respective colours associated with them in the film.

Now comes one of the film’s most beautiful and elegantly precise echoes. The film music of the flashback has been playing all through the scene, and in exactly the same spot – the pause between the second and third iteration of the piano motif (played with strings in the previous scene) – he says, “I had a bad dream,” echoing her “I thought I was dead”. Five words, five syllables, intertwined with a five-note musical motif. Both statements metaphorically describe an experience in a dimension beyond reality. David’s “dream” is not only the struggle with The Orange Man, but also the years spent in depression without contact with his real self – as a consequence of a decision made in virtually the same spot in the flashback. (The statement also points back, of course, to the exact spot when he realised that their marriage was in trouble, as he told her in the bar scene: “I had a nightmare one night and I didn’t wake you up so you could tell me that it was okay”.)

She answers, “It’s over now,” comforting him in his childlike state, which is no longer pathetic, as in the school nurse scene, nor, as in Elijah’s case, unhealthy. It expresses a basic need to acknowledge his own vulnerability. She is his security, filling the role of the letters, written with “her own” yellow colour, on the back of his “superhero outfit”.

Shyamalan follows this transcendence with a scene that is resolutely everyday, but in fact acts in concert with the same motifs. Especially elegant is the continued use of the staircase-as-reconciliation, “hidden in plain sight” through the ordinariness of the situation, as Joseph comes down the next morning. The scene that will now unfold (we will return to it in the second article) – confirmation of his father’s superhero status and acknowledgement that Joseph had been right all along to believe in his father – could not have been more different than the earlier gun confrontation scene in the same kitchen.

Clothing is important with Joseph too: as he comes down the stairs, his T-shirt follows the usual pattern through most of the film of horizontal stripes, but it is now more flamboyant, almost like a superhero uniform, as if Joseph were a sidekick to the real hero, his father. It is also green, David’s colour.

Quite often in the film, Joseph’s clothes will be similar to his father’s. Below, in the series in the top layer, he is wearing a green hood, which seems a foreshadowing of the hood of his father’s green “superhero outfit”. It is the only time in the film that Joseph wears the hood and it falls off as he runs to meet David. In the right-most top-layer image, they leave the park to go weightlifting, both wearing green and red.

David and Elijah: born out of accidents

Unwittingly, David has made a bargain with the devil. Elijah will help him get rid of the “sadness in the mornings” and, in the words of Elijah, “Now that we know who you are, I know who I am. I’m not a mistake.” Having thus resolved each other’s fundamental problems, Elijah’s gloves are off and they are enemies.

The real nature of the bargain is iconised through the freeze-frame above: a stylised, processed shot that flashes past us before each of the three visions that reveal Elijah as the perpetrator of the recent disasters. Here it seem like Elijah’s emblematic blue colour is travelling up David’s arm (as if Elijah were showing his “true colours”). It is not only as if the colour metaphorically transmits the visions, but as if it infects David, who thought all of his problems were resolved, but now gets the rug brutally pulled out from under him. (The handshake is also ironic in the way a hand of “glass” ends up dominating a hand with super powers – which could nevertheless easily crush the former.)

Like any truly worked-through film that aims to operate both on the viewer’s conscious and unconscious levels, Shyamalan is criss-crossing Unbreakable with a large number of parallels, ranging from the obvious to the very subtle, between David and Elijah. The following is a list based on concrete evidence, each item fitting very nicely with the themes and spirit of the story. (Some items are accompanied with screen shots, and will be listed first.)

- Reflections: Elijah is seen as a reflection in three shots, as we discussed here, where we also learned that each shot kicked off Elijah’s three time planes. In David’s case too his “reflection scenes” are restricted to the early parts of the film. In the first occurrence he is reflected in the train window (this is the very first shot he appears – following thus Elijah’s pattern), but without much emphasis. The second and last occurrence is as subtle, but seems much more meaningful:

- In the only reflection shots where we see David and Elijah specifically reflected in a mirror, the scenes take place in a dressing/changing room. Both has to do with beginnings: Elijah is a newborn baby, David is changing into his work clothes for the first time in the film. All of these different clothes have “security” printed on the back, linking them to the raincoat, his “superhero outfit”. So metaphorically one can say that in the film’s narrative his superhero persona is born in this shot. As we saw above, green (David’s colour) was as emphatic there as purple (Elijah’s colour) is in the connected scene below:

- Both Elijah and David tilt their heads in the same characteristic, clearly marked fashion (further elaborated on in the second article):

- David and Elijah are each the protagonists of the only two shots where both the staircase and arch motif appear at the same time, in centralised and “activated” form. It is not surprising that the situations are remarkably similar: both are at train stations; at great personal risk they are about to descend into an underworld; Elijah into the subway where the possibly dangerous gunman is and the staircase itself is treacherous; David into the station area where he will have a series of visions of sordid crimes. (Look how the clean lines of David’s shot vs. the chaotic lines of Elijah’s shot reflects David’s greater mastery of the situation.)

- When David looks at his newspaper clippings, the camera starts closing in on the accident car, seemingly homing in on the front wheel. When Elijah waits in the physical therapy centre, there is a slow, very emphatic track-in on the centre’s logo. So in scenes with both David and Elijah, the camera closes in on circular objects. Both scenes deal with results of accidents and both lead to Audrey: she knocks on the door interrupting David at that point; she materialises inside the circle of the logo. (Also, she was trapped inside the car in the clipping.)

- There is a direct cut from the gaudy comic book store where Elijah is brooding, to the tasteful bar that David and Audrey attend. Here it is the contrast in location that makes up most of the parallel, although both scenes are shot to make the surroundings tower over the characters:

- Also, specific to these parallel story strands, two secondary characters are introduced, the babysitter and the comics store clerk. Both are somewhat eccentric, dark-clad and have curly hair:

- One doctor tells David that he has broken no bones, while in another scene a doctor tells Elijah he has broken an enormous number of bones.

- Both Elijah and David are bestowed with flashbacks, both to pivotal moments of their lives. For Elijah opportunities are opening up (discovering comic books), for David opportunities are closed off (faking knee injury).

- When David recoils from Elijah after he is revealed as a mass murderer, there are alternating shots where the camera tracks out from them. Both through the direction of the camera and the mood created by that, this is an inversion of the exuberant track-in movements on David and Joseph in the weightlifting scene, when David finds out about his super-strength. One scene is about the shock of discovery, the other about the joy of discovery.

- Both save newspaper clippings, David of his football career and his accidents, Elijah of various disasters. These individual strands converge in the epilogue, when they are linked by the same newspaper with the front page story of David defeating The Orange Man.

- David and Audrey are struggling hard to remember whether he has ever been sick. This is an ironic, yet perfect moment to cut to Elijah’s flashback as a 13-year-old, to a situation Elijah never will forget (his first comic book).

- Elijah has three accidents, at different ages: birth, childhood, grown-up – David has three accidents, at different ages: childhood, youth, grown-up.

- Both’s third accidents are connected to trains, respectively railway and subway trains.

- Both fall, respectively down the subway station stairs and down from the veranda into the swimming pool. Both cases are accompanied by the same five-note piano motif.

- Both have at one point taken the decision to stay very safe: Elijah as a 13-year-old refuses to leave the apartment. (As a grown-up he has developed a fetishistic attitude to safety: his car is padded inside and even his wheelchair blanket seems to be padded.) David has more or less withdrawn from life. Both are then encouraged by someone else to engage with a dangerous world: Elijah by his mother, David by Elijah. Both “encouragers” will sow a seed in the other’s mind that will grow into something fantastic.

- David suffers from a sadness similar to the one experienced by Elijah as a 13-year-old.

- Both are connected through movement. When Elijah turns around his first comic book, which is upside-down, the camera performs a dizzying pirouette along with the movement. When he later turns around the second comic book, the camera is still. This creates a parallel: at the hospital the camera performs a pirouette around David, but before he carries Audrey up the stairs David himself is making a pirouette. (Further described in the third article.) To both Elijah and David, the camera pirouettes indicate a disoriented state. In the second cases there is also a further, weaker similarity, in that both are “in command” of the situation, unassisted by camera movement: Elijah turns around the comic without the “help” of a camera movement, and David is now making the pirouette himself.

- Elijah’s chase after the gunman has the air of a nightmare, in which he has to face his biggest fear, breaking bones (by falling down the subway stairs). This might be said to connect to the “dreams” of David and Audrey, respectively the nightmarish fight against The Orange Man and her experience of being “dead”.

- In the bar scene David says, “I just don’t feel right, Audrey. Something’s just not right.” Even though David rejected him at that time, this is an echo of Elijah’s suggestion in a recent scene that, “Perhaps you’re not doing what you’re supposed to be doing.”

- Considering the pivotal importance of the handshake in the epilogue, in retrospect other handshakes in the film take on greater meaning. The greeting between David and the woman on the train becomes interesting, especially since she, a sports agent, talks about a prospective client in terms of “He’s gonna be a god.” This sounds like a prefiguration of David’s own future superhero status, further underlined by the fact that she speaks of precisely a football player. It is also noteworthy that she wears a blue top, Elijah’s colour – thus, there is already in the train scene something that connects David and Elijah. (We will return to all this colour business in the second article.)

- Both are involved in encounters with strangers that they engineer to take a personal turn: David tries to seduce the woman on the train, and in the physical therapy centre Elijah starts to ask Audrey about her marriage and about David. (Both scenes include one member of the same married couple.)

- The staircase in David’s home becomes emblematic of his estrangement from Audrey. When he turns his back on Elijah and leaves in the epilogue, he walks up a mini-staircase, of perhaps only two steps – it almost looks like a silly little joke amid all the seriousness of the situation.

We shall end this chapter with a very subtle and intricate parallel made by sound. Both David and Elijah are, in a sense, born out of accidents. David’s real self of unbreakability is “born” out of the train accident. Elijah breaks both his arms and legs when he is born. In the film’s opening seconds before the prologue starts there are two distinct sounds. One is some sort of rumble. The other is some kind of electric static. They must be there for a reason.

In the scene where David is looking at his news clippings, there is a very similar rumble. It starts when the train accident clipping appears in the shot. The electric static sound also appears (almost inaudible, I had to turn my headphones to maximum to properly hear it; it will probably be easier in a movie theatre). The context, then, seems to connected these sounds to an accident. Back in the film’s opening seconds, out of the soundscape of rumble and static, there rises the scream of a newborn baby. (The screen has contained no visuals so far, as if to express the baby’s lack of vision before birth.) The sounds seem here to represent the “accident” of Elijah breaking his arms and legs when born.

There is a bit more to this sound business. In the news clipping scene, there is first a rather faint high-frequency sound that appears over the clipping of the car accident. It then converges with the rumble that starts when we see the clipping of the train accident. This fusing of sounds seems to connect the car accident with the train accident – a very subtle indicator of how these two accidents will be important, connected elements later in the plot. (It acts in concert, of course, with the connection made by the images, here). The rumble also seems related to the humming that appears when blood starts to come out of the dying survivor’s abdomen in the hospital emergency ward. The hum increases in strength as the bleeding continues and gets very loud over the next, strangely distant scene, where David meets his family in the reception area. So again, rumble/humming is connected to death and misfortune, and it reappears just before Elijah starts to recount the three accidents in his first scene with David.

David and The Orange Man: Security Man vs. Maintenance Man

Let us start this last character connection chapter with a wrap-up of some minor relationships. Audrey breaking a leg in the car accident could be deemed an echo of Elijah’s bone illness, but it is not part of a larger system. We are on somewhat firmer ground with Joseph and Elijah. In their introduction scenes (if we disregard Elijah’s birth in the dialogue), they are both children of roughly the same age, with Joseph a couple of years younger (age 11? – actor Spencer Treat Clark was born in 1987). Their first moments are connected by the mise-en-scène’s untraditional use of a TV set: Joseph is watching TV upside down and Elijah is eerily reflected in a dark TV screen.

Childhood traumas are quite central to the film. Both are suffering from psychological problems: Elijah from his illness and being harassed by other children, Joseph from an unspecified malaise probably rooted in his father’s rejection of him. David joins this theme through his drowning accident when he was “little younger than Joseph”. And God knows how the two children that David saves from The Orange Man will be affected by their captivity and the murder of their parents.

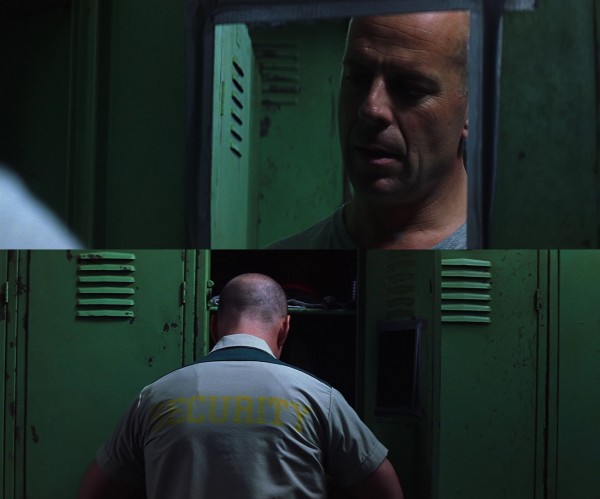

The ground is very firm, however, when we look at David and The Orange Man. The latter is working as a janitor (like Mr. Heep in Lady in the Water) and his appearance seems designed to be a mirror image of David. Both work in large public places (railway station/football stadium) with many people around, are dressed in single-coloured uniforms (green/orange) and wear a cap with a visor. There is also a connection using continuity: when David follows The Orange Man after work, the latter is seen climbing a big outdoor stairway. The next camera position is at the top of the stairs, so we expect to see him complete the climb, but it is his shadow David that appears instead.

The fact that they both hold menial jobs is well suited to the film’s theme of transplanting the fantastic into everyday life. This is emphasised further, as exemplified in the below montage:

“Security” seems a pun on the comic book that is either named Sentryman or Century Comics – the film is rather confused about it – that at one point gives Elijah a key idea. The same word is on the back of David’s shirt (here) and raincoat. When David starts following The Orange Man inside the railway station, the latter disappears behind a door. The camera is lingering for a long time on that door, as if bestowing some special importance on the situation. The door is marked “Maintenance”, with roughly the same colour and letter stylisation as David’s “Security”. A reasonable interpretation is that the coming struggle is an everyday transposition of a superhero situation between two characters we could name “Security Man” and “Maintenance Man”.

The above situation is also interesting. In the top image David has been pushed into the swimming pool. The tarpaulin covering it is slowly giving away, sucking him in. Visually it looks like David is being swallowed up by his own fear of water, emphasised further by the tarpaulin having the same colour as David’s raincoat. Later (bottom image), when David starts fighting The Orange Man, at one point it looks like he is being swallowed up by David’s raincoat. Like his local problem, his fear of water, tried to consume him but he overcame it, David is now overcoming his global problem, his fear of interacting with the entire world.

There is a final parallel, however, this time between the villains. In the epilogue Elijah’s mother lectures David about super-villains: “…there’s always two kinds. There’s the soldier villain who fights the hero with his hands and then there’s the real threat – the brilliant and evil arch-enemy who fights the hero with his mind.” The Orange Man is obviously the soldier villain and Elijah turns out to be the arch-enemy. [EDIT 14 Feb 2019: With the advent of Glass, the soldier villain reference obviously must be extended to comprise The Beast.]

We have already seen how two scenes of Elijah’s past and present were subtly interlaced, and Shyamalan now sets up an even more ingenious connection between scenes. In the previous example, music and a vaguely similar geography and narrative did the trick; now it is scenography and pure mise-en-scène at play.

The similarities do not end with this, however. In both cases, the characters have left a space with a large number of people (there is an comic book art exhibition going on in Elijah’s gallery.) On the left, both passages have a wall. On the right, in the Orange Man scene there is a series of pillars, and in the epilogue there is a series of rows of comic book racks. Like Elijah is entering his inner sanctum, the room into which The Orange Man disappears has a similar function of private space, even marked “No admittance” and “Employees only”. (Elijah was even born in such a behind-the-scenes room in a public place.) The door has three windows in it (he also walked past three windows in the corridor), creating a similarity to the three windows right behind Elijah. The crowning touch is that the Orange Man is pushing a wheeled dustbin, while Elijah is pushing his wheelchair.

In itself, such “transportation” that makes up the bulk of these scenes, through its very eventlessness, is an excellent tool for building tension and foreboding – brilliantly used by, for example, Robert Siodmak in his late 1940s films – and suits Shyamalan’s often-used strategy of slowing down the pace. It is is reason to believe that all these underlying similarities with a scene about a murderer will create an additional vague feeling of uneasiness in the viewer’s unconscious. Looking at the shots above it looks blindingly obvious, but the parallel is cleverly hidden – it took this author almost twenty viewings to become aware of it, and then only stumbling upon it while investigating something else. Part of the difficulty could be the hypnotic quality and agitated music of the first scene, and also the difference in mood initially – the first scene starts with total shock after the discovery of the murder, and the epilogue with relaxed festivity and David’s relief over having solved all his problems.

*

Similar as they are, Unbreakable seems to be even more structurally ingenious and complex than the already very complicated The Sixth Sense. Being less story-driven allows it space to develop many strands of motifs, and other forms of interconnectedness, that not only give the film coherence and the ability to influence the viewer’s unconscious. Operating with a high number of motif strands has the advantage that they sometimes will intertwine in ways that produce unforeseen, but relevant meanings, helping create a work of art that is hard to exhaust.

In this article we have looked at character “motifs” – from an analysis point of view, all characters and their attributes can be viewed as motifs – and in the second article we will look at other types, whose behaviour is not any less complex.

*

Addendum A: An unbreakable bond – connections to The Sixth Sense

Unbreakable contains an enormous amount of connections/references/similarities to The Sixth Sense (TSS in the following), forming a curious, unbreakable bond between these two films. This is clearly over-represented, to the point of obsessiveness, and thus any serious analysis must deal with it. The following is an exhaustive list, in order of appearance in Unbreakable.

- Although extremely different in tone and number of characters, both opening scenes take place in a limited space whose precise layout is deliberately obscured (the basement scene in TSS is analysed here).

- The colour purple (and later blue) will be closely connected to Elijah, like red was connected to ghosts in TSS.

- Both films cast Bruce Willis against type.

- The young woman on the train wears a top akin to Anna’s dress in TSS (explained in the image above), in both films the clothes are used in the hero’s first scene.

- To better seduce the woman David removes his marriage ring, a faint yet meaningful echo considering the all-important on-off status of the hero’s marriage ring in TSS.

- Just before the film cuts away from the train accident scene, the surroundings, seen through the window, turns unnaturally white around the hero’s head, alluding to the way Malcolm disappears into the whiteness at the end of TSS, both scenes dealing with death.

- In TSS we could believe that the hero survived the gunshot in the prologue, but he was actually dead – in Unbreakable this is twisted around: it is absolutely unbelievable that he could have survived the train accident, but he is actually alive.

- In TSS there was a motif of thrice-occurring elements. I hesitate to bring it up here, because in Unbreakable it seems not that over-represented and thus less analytically pertinent. Still, in light of its ubiquity in TSS it might be of interest: there are three acts of terrorism; three visions of those and three visions in the railway station before the Orange Man is introduced; three mentions of “Mr. Glass”; three mentions of sadness, the important metaphor for David’s depression; David rejects Elijah three times; both David and Elijah suffer three accidents, at three different ages; three periods of both Elijah’s and David’s lives will be important to the film; three intimate scenes where David and Audrey discuss their relationship; Elijah crashes into the sales racks in the comic book store three times; The Orange Man twice rams David three times with his elbow during the fight; at the hospital the doctor asks David three questions about his health; Elijah ridicules his customer with three ironic rhetorical questions; the doctor tells Elijah about three areas of injury (right hand, ribs, right leg); the schoolboy named Potter or his football-playing cousin occur or are mentioned three times; Elijah has three computers in his inner sanctum.

- David’s house is decorated with pictures of plants and flowers, like Malcolm’s house.

- Arches are possibly the most prevalent visual motif and was also present, although in milder form, in TSS.

- Staircases are also very important, like in TSS (not as a recurring visual symbol though): the staircase up to the bedroom where Malcolm was shot; down to the cellar where he lived as a ghost.

- There is a memorial service in a church for the train accident victims, while there was a similar service at home for the deceased girl in TSS.

- Both films deal with two different families and how one member of each will interact.

- Both films deal in indirect ways with absent fathers: David is distancing himself from Joseph and also plans to leave the family, and Elijah does not have a father, while Cole’s father in TSS has left that family.

- 13-year-old Elijah says, “They call me Mr Glass at school,” while Cole in TSS was called “freak” by his classmates.

- His mother gives Elijah a present, while Anna gives her employee Sean a present in TSS.

- Both the box the present comes in and the present inside are wrapped in a colour important to the film (purple); the same in TSS except that the box is not wrapped but itself is red.

- Both presents are instances of narrative art forms, and while the book in TSS was a first edition, the comic book is marked “Limited Edition”, which also becomes the name of Elijah’s comic book shop/gallery.

- Both films contain meta-references to Shyamalan’s twist endings: Elijah’s mother says the story in the comic book has “a surprise ending”, while Cole says Malcolm has to “add some twists and stuff” to his bedtime story.

- The grown-up Elijah is dealing with a customer situation in a fancy shop, accompanied by classy music by Bach, and gives a thorough explanation of the qualities of the sales object – all of which is replicated in the antique shop scene in TSS, except Bach is substituted with Schubert (also, in both scenes the expression “wrap it up” is used). Last but not least, Firdous Bamji is cast as a customer in both films, to additional, meta-comedic effect since he is slammed for buying too expensively in Unbreakable and too cheaply in TSS.

- The hero and his wife have huge communication problems (but the roles are reversed as to who is trying to bridge the gulf between them).

- David has also big communication problems with his son, like between Cole and his mother in TSS (but again roles are reversed; in Unbreakable it is the child who tries to bridge the gulf).

- Both films feature emotionally troubled children (Joseph, Elijah and Cole).

- Both films features a depressed hero, in Elijah’s office distilled by David into the word “sadness” – the same thing that Cole detects in Malcolm’s eyes in TSS.

- When Audrey asks David if he has been unfaithful, she says his answer “won’t affect me either way.” A similar reassurance happens in the kitchen scene in TSS, where Lynn says “I-I-I won’t get mad, honey. Did you take the bumblebee pendant?”. In both cases the reassurances are proven wrong.

- Audrey thinks their marriage deserves a “second chance” after David survived the train accident, like Malcolm, after having “survived” the gunshot, gets a second chance to help a disturbed child similar to Vincent Grey in TSS.

- The first suspense scene in Unbreakable, Elijah chasing down the gunman, starts at approx. 41 minutes, not far from the first really tense scene of TSS, when at approx. 50 minutes Cole tells Malcolm that he can see dead people – in both films, these scenes provide the first confirmation of the presence of supernatural powers.

- These powers are both an ability to sense the presence of certain types of beings: David can sniff out criminals, Cole is seeing ghosts.

- David discovers his true physical strength through weight-lifting in the cellar, an important location, also for revelations, in TSS.

- The weightlifting scene is shot and edited in a way reminiscent of the mind-reading game, an extended, deliberately paced scene applying unity and variety to a constrained set of devices (the scene will be further discussed in the third article).

- In the same scene Joseph is placed at varying distances from the weightlifting action, echoing how Cole was positioned at various distances from Malcolm during the mind-reading game.

- Curiously, extreme colourfulness in these films are almost exclusively connected to health care situations: the physical therapy centre scene causes Unbreakable to suddenly explode in colours, the office of the school nurse is very colourful, and in TSS the scene in the paediatrics clinic is foregrounded with a strange concoction of many-coloured hoops and spirals.

- Elijah asks Audrey a personal question about her marriage. After hesitation and protests, she openly talks about it after all. This is reminiscent of Cole pointing out that Malcolm’s eyes reveals his sadness, Malcolm countering with, “Not supposed to talk about stuff like that,” and then immediately spills the story of his life. Audrey and Malcolm are both health care workers in a professional situation, and their willingness to talk reflects their need to lighten their mental burden.

- All perpetrators in David’s visions are dressed in strongly-coloured clothes, directly pointing back to the murderous mother in bright red in TSS.

- The perpetrators are often violent and their crimes are revealed through visions of a supernatural nature, a parallel to the visitations of the ghosts in TSS (although their violence or threatening appearance actually was a cry for help).

- David’s visions are first showing glimpses of everyday American violence before the film focuses on a particularly gruesome case, like in TSS the early ghost appearances and then the case of the poisoned girl. The colour-coding of the Orange Man and the mother in red is a clear parallel between the two culminations.

- Joseph was hurt by the other kids during “play rehearsal”, a clear echo, however faint, of the importance of school plays in TSS.

- The school nurse says that the children still talk about David’s childhood drowning accident, “Like it was some sort of ghost story,” an obvious reference to TSS.

- She reminds David that she had red hair in younger days. In TSS the colour red was always connected to ghosts, often signalling their appearances – so it seems noteworthy that this particular hair colour was chosen in the screenplay and that she will immediately start telling the “ghost story” of Malcolm’s drowning.

- The story goes, “Did you know there was a kid nearly drowned in that pool? He lay on the bottom of the pool for five minutes. And when they pulled him out, he was dead,” which is another play on the hero’s alive-or-dead status in TSS.

- David attended once the same school as Joseph, which echoes Stuttering Stanley having attended the same school as Cole, the accident of the fire in his school days echoing another legendary accident, David’s drowning.

- The communication problems between parent and child reach their apex in a scene in a kitchen, which is also mostly filmed in one long take.

- In both films the dangers of gun ownership are exemplified: Joseph uses a gun in the kitchen scene and in TSS there is a ghost of a boy with a gunshot head wound – in both cases it is explicitly stated that it is their father’s guns.

- In both films the hero are held at gunpoint by a much younger and emotionally overwrought person, and while Joseph says “I’ll just shoot him once,” Malcolm was shot once by Vincent Grey.

- In the kitchen confrontation scenes in both films, the instigators of the conflict are hurt at their absolutely weakest points, causing them to break down. David gets Joseph to put down the gun by threatening to leave the family, playing on Joseph’s worst fear of losing his father. By Cole being unable to fully open up to his mother, she badly loses her temper with him, since the quarrel about the bumblebee pendant activates deeply unresolved issues with her own deceased mother.

- Joseph is playing with superhero action figurines at one point while Cole was playing with toy soldiers all through TSS.

- The hero and his wife meet in a classy bar to discuss their marriage problems, which alludes to the scene in the classy restaurant in TSS, where Malcolm arrives too late for their marriage anniversary dinner, both scenes filmed in one long take, with stylised, slowly approaching camera movement, and with red and yellow flowers on each table (scene has diegetic jazz music, like in another, equally intimate scene in TSS where Malcolm and Anna celebrate his citation).

- In both films a recorded audiotape becomes an important turning point: the phone answering machine message from Elijah, and in TSS the tape of Malcolm’s past session with Vincent Grey.

- When David enters the railway station, the scene starts with a black screen which turns out to be David’s back, like the start of one of the scenes in the post-funeral sequence in TSS (analysed here).

- At the start and end of the car accident flashback, a peculiar, jittery type of slow-motion is employed, like in TSS just after Malcolm was shot and when Lynn is dragging Cole out of the big closet during the birthday party.