The Village, Part II: A tapestry of characters

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the second article about The Village. The first one is here, the third here. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

The first article about The Village was devoted to delineating the film’s story arc and presenting its supporting cast of motifs. With such a complex film this is a major task, so to keep that article at a manageable length, general comments on the film had to wait to this installment. The rest of the article is about the cast of characters and their tapestry of relationships. The goal of the exploration is not so much to describe their personalities – which come across splendidly in the film – but to further illuminate structure, an ongoing concern in this analysis project.

Thus similarities and contrasts between characters will be examined, with a special emphasis on subtext and how that is expressed through mise-en-scène. This installment is more text-based than the other The Village articles, but screen shots are still eagerly used whenever useful – not least in the last chapter, when possibly the most emotional and subtle scene of Shyamalan’s entire oeuvre is examined in high detail.

Table of contents: After the general comments, Lucius, the most complex character, is awarded a special spotlight (his fearlessness, his loner personality and his oratorical side). There is a short introduction about character relationships, the film as an ensemble piece, and its unusual strategy towards the issue of protagonists. Then a number of pairings of characters are examined: Lucius and Noah, Lucius and Ivy, Ivy and Noah, Ivy and Mrs. Clack, Ivy and Kitty, Ivy and Edward, Edward and Alice. (There are two addenda: addendum A details references to other Shyamalan works and addendum B summarises the occurrences of Ivy’s “super-hearing”.)

*

In order to discuss the film properly, I will have to reveal the whole plot, including the plot twist at the end.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of The Village, here is a brief outline of the plot. There are several slide shows. Each show can be restarted from the beginning by clicking on the current image to enlarge it and then return to the article. There are also links to various points inside the other Shyamalan articles. Dependent on resources, on occasion web browsers will miss the exact target point on the first attempt, since images are loaded after text, which may cause a shift. If you do not reach the expected point in the other article, try again, then the browser will meanwhile have corrected itself.

A cornucopia of pleasures

The Village is a work that casts a singular spell. This author remembers well how the first few screenings virtually forbade any thinking, just instilled a mesmerised fascination. When the film shifts gears with the surreal quest into the woods, it feels like a metaphor of obsession as powerful as anything in cinema. The portrait of a seemingly happy community nevertheless in the grip of collective neurosis, with peculiar rules or incidents that might at any time turn peace into chaos, here escalates into a nightmarish struggle of opposing forces, clad in feverish colours against a bleak, spidery landscape. Everything seems wholly irrational and confused, but even though we are helplessly locked into the blind protagonist’s perspective, the film’s odd, almost ritualistic repetitions seem to indicate there is a method to the madness.

The Village contains so many aspects competing for attention when thinking back on the film that one is hard pressed where to begin. Like more or less all works in the Shyamalan pentalogy, it is a mood piece, given an indefinable rarefied allure by the highly distinct camerawork and mise-en-scène. Although it certainly has dramatic high points, not much really happens: build-up is as important as climax. It has great pastoral beauty, mostly concentrated in the first part, before the forest loses its foliage. There is both a warm, naturalistic tone, as in the scene at the Resting Rock, but also a stylised lyricism, for example in the windy scene where a young woman discusses a romantic secret with her father, which is shot with an oddly fixed camera. James Newton Howard‘s music, featuring Hilary Hahn on otherworldly solo violin, spans quiet lament, triumphant uplift, pained soaring, modernist frenzy.

More than the earlier films, there is a minimalist feel to the visuals, but still they manage to feed the usual Shyamalan complexity – The Village is a treasure trove of echoes, parallels and other structural riches. The pacing is very slow, but nevertheless the film is experienced as having energy and rhythm. There are bold changes of tone: some scenes overflow with dialogue, almost demonstratively so, at other times words are banned, with a stretch of 14 and a half minutes with virtually no dialogue. During the quest there are three and a half minutes where we hardly see the heroine’s face. This section is marked by continuously inventive staging, but without losing its sensitivity and eye for emotional nuance towards the character of Ivy.

She is played by Bryce Dallas Howard – with a radiance not unlike that of Jessica Chastain – who during the quest is immersed in her character to an electrifying extent, pathetically floundering with irrational fear, plunging herself into any physical hardship. Inside the village she is intriguingly alluring and vivacious. She is leading an ensemble queuing up with memorable performances: Adrien Brody as the mentally challenged Noah with a wide assortment of tics but also engagingly childlike enthusiasm. William Hurt as Edward, the fatherly village head, in many scenes acting virtually only through his sonorous voice. A cast-against-type Sigourney Weaver as Alice, sometimes borderline comical, more often a tragic figure. A very solid Joaquin Phoenix as Lucius the loner. The film also features a large cast of secondary characters who nearly all are allowed at least one step into the limelight. The extras, especially the children, are a careful selection of interesting physiognomies believably inhabiting a bygone era.

There are a number of “indestructible moments” that never lose impact however many times one sees the film. The final inhumane knife stroke during the murder attempt on Lucius. Noah’s unbearable air of having totally lost his way on the porch in the aftermath. Ivy slapping him repeatedly in the face in hateful revenge. The ice rain for a brief moment turning the woods into an enchanted fairy-tale landscape. The brutal sound effect as Ivy is falling into the pit. The subtle underlying feelings of the “It is all that I can give you” scene between Edward and Alice, perhaps Shyamalan’s finest emotional moment ever. Ivy’s irresistible lowering of her voice. The steely determination of her tone and blind eyes during the “I ask permission” monologue, when she demands being allowed to go to the towns to fetch medicine for Lucius.

The few horror scenes sprinkled over the film are executed with Shyamalan’s usual precision. But there is at times an embrace of the irrational, unseen to this extent in his earlier films, which gives The Village a truly wild dimension. But simultaneously one also has the feeling that it is a super-controlled director using this very quality to make it seem that the film is out of control.

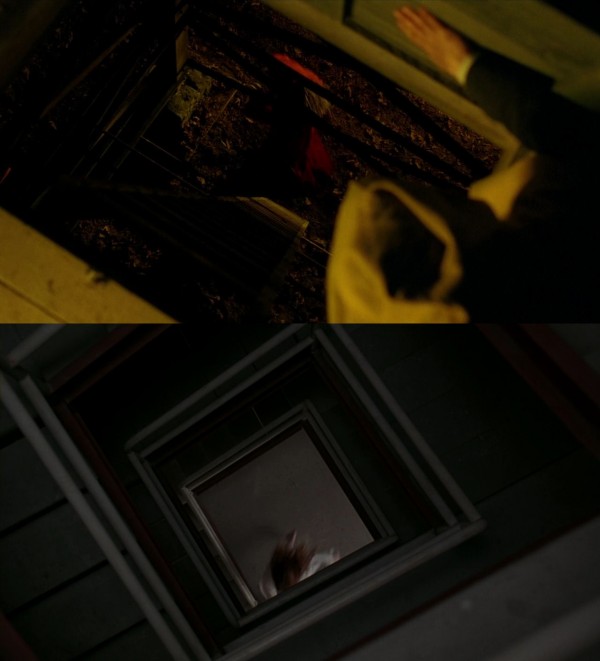

The prime example is, after what seems like an eternal build-up, the dreamlike but absolutely horrifying appearances of the red creature during Ivy’s quest, in clearly defined stages as if part of an unfathomable ceremony. Another fearsome moment, culminating with a creature closing in on Ivy’s hand as she stands in a doorway, is horror poetry, staged to make time seem to stand still. Speaking of stopping time, one must not forget the Ozu-like pillow shots, for example of bells and lamps, that regularly appear as lyrical punctuation of the narrative.

Are there no faults with The Village? Some late scenes seem to creak a bit: the guard shack scene (details here) and the first part of the last shot (here). Obviously, some of the very slow, chatty scenes among the elders lack the intensity and beauty of the rest of the film. But after getting to know the film’s concerns and the characters, this author thinks they are a nice change of pace, with a charming, altmodisch feel for the slowness and down-to-earth matters of the olden days. The “bad dialogue” – a stumbling block for many – is deliberately written in a faux old-fashioned way, and works fine.

The Village was not exactly warmly embraced in its time, but its standing seems to have ripened with age. Virtually every time one looks it up at the IMDb nowadays, there is a new, enthusiastic User Review on the front page, not seldom tinged with bewilderment about its original reception. In 2004, Shyamalan’s unique hybrid of Hollywood mainstream movies and formal devices one rather associates with European art films resulted in often demanding works – Signs was designed to have more popular appeal than Unbreakable, but still had its share of strangeness – that for each time had a more difficult time being accepted by critics and audiences. (My chronologically first Shyamalan article, about Lady in the Water, starts out with a brief discussion of the unfair criticisms. His excellent new film, the absurd theatre of The Visit, seems to have represented a critical shot in the arm, at least from quite a few American reviewers.)

Some of the receptional problems with The Village probably had to with expectations. But although (mis)marketed as a horror movie, the glacially paced, stylised formality of the opening couple of shots clearly signals a somewhat higher ambition than frightening the wits out of an audience. That did not prevent a range of peculiar complaints about the film, which received a lukewarm critical response (it scored 44 at Metacritic).

Especially the (virtually obligatory by now for a Shyamalan film) complaints about the twist being unsatisfactory is revealing as to the barrier against looking at his films as works of art – as if 95 percent of every film is merely a set-up, trundling along towards its ending, the entire reason for the film to exist. This is a rather childish way to look at narrative art, particularly with a film like The Village, packed as it is with ideas, meaning and beauty. Would a personal dislike of what Rosebud finally is revealed to be, invalidate the whole body of Citizen Kane?

But enough about such matters. Let us instead dwell on the shot in The Village that possibly offers its most refined beauty. Below is its start and end points, a work of art by master cinematographer Roger Deakins. A band of extras play villagers cowering in the safety of their basement during the creature invasion, with the camera tilting softly (they are all linked by the colour green):

As the above has indicated, The Village is a rather spectacular film. The most “spectacular” of the articles are the first one, tying the ending of the film to its start and its extensive apparatus of motifs, and definitely the third one, exploring the scene of attempted murder (including build-up and aftermath) and the quest into Collington Woods. The rest of the current article will deal with more down-to-earth matters, the patient accumulation of details that quietly adds resonance to the characters and their relationships.

Lucius the fearless

Ivy asks: “How is it you are brave when all the rest of us shake in our boots?” Lucius’s lack of fear is unique among the non-elders – even Ivy is terrified about his idea to go to the towns, and Noah is a special case – and this is amply reflected in the mise-en-scène. The village boys play a game to see who dares stand longest at the border with the back to the sinister forest. When they return, their recent abject fear replaced by merriment within the safety of the village, Lucius too appears in the square (above).

This shot encourages comparisons in several ways. The infatuated Kitty has praised the fact that Lucius “doesn’t joke or bounce about,” so here we see him in contrast to the childish boys. Later we learn that the fearless Lucius holds an unbeatable record at the game, so it is fitting that the champion should turn up at this precise point. After Lucius has dared to enter the woods to test the creatures’ reaction – his theory is that they may let a fearless man with noble intentions pass through the woods to the towns – the camera lingers on how he walks out again at a measured pace, even after having glimpsed a creature, once more in comparison to the youths’ panicked escape just before the scene on the square. Lucius even echoes the game by walking out with his back to the danger.

Lucius is contrasted more specifically against Finton Coin (Michael Pitt) and Christop Crane (Fran Kranz). When he sits with Finton in the watchtower, he does not bother wearing the cloak of the “safe colour”. (And during his forest foray, he boldly takes off the hood, to let the creatures “read” his pure intentions.) Finton hides his anxieties from the rest of the village – he says to Lucius “I do hope no one saw you,” because Finton is supposed to be alone on guard – so he is unfortunately chosen as an escort on Ivy’s quest.

Her other escort is Christop Crane. It is ironic that the fearless Lucius is substituted with precisely Christop as the object of Kitty’s puppy love, since even though Christop is brashly pushing the others during the game, he becomes the first one to abandon Ivy. Thus she ended up with two of the most wretched villagers as escorts. Before Finton leaves her, he even pleads with Ivy to follow him back to village border, to make him safer.

One more contrast between Lucius and Christop: a running gag with the latter is his obsession with avoiding wrinkles on his shirt. This is not particularly funny, but serves a useful purpose: while Christop is shown to be concerned with the silliest of details, Lucius is thinking big and bold thoughts. And while Christoph avoids closeness with others because of his shirts, Lucius’s loner status is an existential thing. Christop’s shirt fixation can of course also be seen as a symptom of the village’s underlying neurosis and obsessive thinking.

Lucius the loner

Lucius Hunt is a loner who only thinks of his community. The elders’ reaction when he appears with his first petition clearly paints him as someone seen as an eccentric. As the only villager without fear, it is natural that he should be an outsider as well. Lucius also comes across as highly introspective – he suffers from the loneliness of being special.

The pre-village photo in Edward Walker’s secret box, revealed late in the film, includes him as a baby. Lucius is probably about as old as his community, so being “a child of the village” bestows upon him a uniqueness befitting his eccentricity and loner status. It is worth noting that he was close to another child, Daniel Nicholson, who has just died at the start of the film, and this death becomes a driving force for his plans to go to the towns for medicine.

The pre-village photo in Edward Walker’s secret box, revealed late in the film, includes him as a baby. Lucius is probably about as old as his community, so being “a child of the village” bestows upon him a uniqueness befitting his eccentricity and loner status. It is worth noting that he was close to another child, Daniel Nicholson, who has just died at the start of the film, and this death becomes a driving force for his plans to go to the towns for medicine.

Lucius’s apartness is another aspect constantly supported by the mise-en-scène and editing. While most villagers are shown in harmonious companionship with others, often expressed through appearing in pairs and fours, he is almost always seen on his own, isolated. The earlier shot of the simultaneous appearance of Lucius and the four young men visualises individualism versus the collective. When all hell breaks loose during the creature invasion, he is seen, in that same square, standing out from the others milling about, through his purposeful entrance and as a shadow close to the lens.

Except when saving others during that sequence, he is never seen to touch anyone – until he saves Ivy from the creature by grasping her hand. This sets off a chain of touching: he again grabs her hand to protect her from the commotion of the interrupted wedding dance, then it culminates in the second porch scene, where he declares his love, before touching her face and kissing her (for visuals: here and here). The pervasive hand motif of the film is otherwise denied Lucius, the absence of touching anyone else an extension of his early refusal to touch Ivy (paradoxically, because he loves her).

While they are speaking in the Resting Rock scene – well, Ivy does almost all of it! – they are never shown in the same shot, and Lucius is always further away from the lens (for example here). The below slide show presents various strategies to set him apart. There is always a gulf (or a table) between him and his mother. In the watchtower scene with Finton and the Kitty scene, he is confined to a markedly different plane of the shot. During the firewood scene with August they never share a shot, except for the last one, barely, where Lucius is seen over August’s legs. Before he ventures into the woods, he is visually separating from the community, represented by not just one companion, but a pair, a common way of expressing harmony in this film. (The only person he is close to for some time – demonstratively so! – in the earlier part of the film is Noah, at the Resting Rock, but the irony is that Noah will eventually try to kill him.)

The first porch scene offers a telling example:

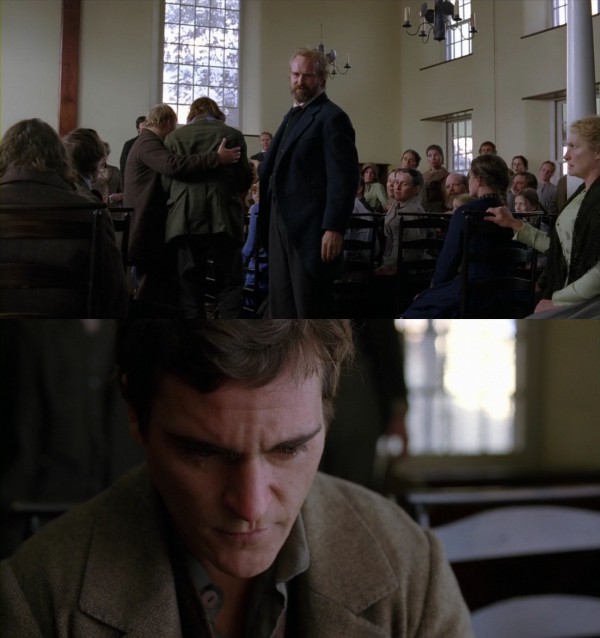

In the second town hall meeting, after Lucius has admitted it was he who breached the border, he sits apart, far back in the hall, the others emphasised as being at a distance:

But then an overwhelmingly sensitive moment is conjured out of thin air: a warm bonding between Edward and Lucius, leader and loner. As the spiritual head of the village, Edward is its father figure, also to Lucius, whose biological father died around the time of his birth. Edward says: “Do not fret. You are fearless in a way that I shall never know,” accompanied by the film music at its most soothing and swooning. Then the film cuts to the wedding between Kitty and Christop where everyone is together, Lucius too.

Edward went down on his knee to address Lucius, marking the fourth Shyamalan film in a row when an older character does this to a person of a younger generation. Before they have always been children, but as we said, Lucius is a “child of the village”.

Edward’s behaviour also recalls his concluding “motto” from the heated elders council meeting late in the film: “The world moves for love. It kneels before it in awe.” Here it is a sign of Edward’s tremendous respect for Lucius’s innocence and purity.

Lucius the orator

Lucius is a man of few words. Both his mother and Ivy are pressing him to speak his mind, and this causes a tiny moment of (between-the-lines) humor in a rather serious-minded film. Alice asks: “What goes on in that head of yours? Say something, Lucius.” Then Lucius is saying something, but instead of confessing why he wants to defy fate by leaving for the towns, with almost autistic literal-mindedness he answers: “Finton Coin is in the tower, and I’ve promised to sit with him.” Alice just shakes her head.

Lucius’s mission is exploring the world and collecting information, often by imploring other people to speak their minds. His only line in the tower scene is: “Do you ever think of the towns, Finton?” In the first porch scene he is inquiring whether Ivy might not miss the ability to see. During the firewood scene he listens carefully to August’s drowsy ramblings. The observant Lucius could easily have picked up subconscious hints from the elders about the superior conditions (in some respects) of the towns, which could explain his urge to go there.

His awkwardness with others is palpable. The first thing he says to Ivy in the film is: “You run like a boy,” a compliment received with some ambivalence. (Later, Ivy is professing an interest in the game the boys play at the border – is this a lie to please Lucius?)

Instead he likes to write manuscripts. Twice, he presents petitions to the council, and also his confession at the town hall meeting comes in writing. It is revealing, in many respects, to examine these petition scenes, also in conjunction with the film’s ongoing visual demarcation of his apartness. In the first scene, he is never shown in the same shot as the others:

During the second scene, the reaction of the elders is even more displeased. But here (only interrupted by a flashback where Noah points out some rock carvings) the camera tracks out, to include Lucius in a shot with all the others. This might reflect a new determination from Lucius to make his mark in the community – in parallel to his later increasing closeness with Ivy – but it also shows that Lucius has become a force that cannot be ignored any more: like the camera includes him, he is pressing his will on the elders (they immediately push back, for in the next scene Alice tries to dissuade him from his plans by telling him the secret of his father’s gruesome death in the towns):

Both “performances” are staged in perfect symmetry, also in scenography…

…except for the only unbalancing element: the cloaks of the “safe colour” on the wall:

Amazingly, the increasing amount of cloaks almost seem to be counting up the number of petition scenes. And possibly reflecting the growing importance of Lucius, and not least the increasing danger to the village: the otherwise perfect symmetry of the shots might symbolise the harmony of the village, and the unbalancing cloaks are connected to the threat from the creatures.

In the second porch scene with Ivy, Lucius abruptly finds his own voice, launching into a monologue he usually would have scripted. It even has a punchline: “And yes, I will dance with you on our wedding night.” For the first time, he speaks as well as he writes, enabling him to tear down a psychological barrier: suddenly he just goes with the flow, and his love for Ivy virtually declares itself. Speaking of declarations: the depth of emotion is striking compared to the utter naivete of Kitty’s declaration to Lucius. (The “writer” Lucius points forward to the central character of the author in Shyamalan’s next film, Lady in the Water.)

Character relationships

The Village is a true ensemble piece. Its main characters can be divided into several layers. First the protagonists Lucius and Ivy, plus Noah Percy as the third important character of their generation. Then Edward and Alice among the elders. A third stratum of lesser characters who will at certain points step into the limelight: Kitty Walker and Finton Coin of the younger generation, August Nicholson, Mrs. Clack and Tabitha Walker (Edward’s wife) among the elders. Finally, a fourth layer of some importance, for example the elders Mr. and Mrs. Percy and the doctor, and among the younger, Christop Crane and Jamison (Jesse Eisenberg in an early role).

Lucius, Ivy and Noah are friends who seem to hang out together. They share some important characteristics. They all breach the border to venture into the woods. They are at some point said to be safe from the creatures, for a variety of reasons. In Lucius’s first petition, he says: “Creatures can sense emotion and fear. They will see I am pure of intention, and not afraid.” In the second one, he states that “because of [Noah’s] innocence, those creatures who reside in the woods did not harm him. This strengthens my feeling that they will let me pass if they sense I am not a threat.” Before Finton abandons Ivy during the quest, he says: “You will be safe. They will not harm you, because you cannot see. They will take pity on you, the way they took pity on Noah”.

Right from the outset, the village is emphasised as community: we are never allowed a proper look at anyone’s face during the funeral ceremony. The ensemble feeling is also encouraged by the fact that Lucius and Ivy are introduced at various later stages, and seem intentionally completely out of sight during the gathering following the ceremony. Noah is introduced there, but the film’s first minutes are still dominated by community and larger collections of people. Lucius does not appear until about eight minutes, doing his petition at the first council meeting. Ivy is first seen after about fifteen minutes, but only as a mysterious person with her back to the camera, comforting Kitty after Lucius has rejected her “proposal”. She is properly introduced about two minutes later, in striking fashion: shown in two clearly marked, stylised positions, frontal and in profile related to the camera.

The Village is also interesting for its “twisty” way of dealing with protagonists. First we think that Kitty will be a central character. Then she is superseded by her sister Ivy, and thereafter relegated to fleeting appearances. Noah is around from time to time. It is Lucius who appears as the foremost driving force of the story, however, although paradoxically he is a rather passive character. But suddenly he is assaulted, and together with the aggressor Noah, he virtually vanishes from the film for its last (roughly) 45 minutes. It is a real narrative extinction event, for neither is Kitty seen after that point – almost everyone that one was led to believe would be central has gone. Perversely, even though Lucius is in fact present in several scenes, except for one of them we never see his face! One is almost tempted to speculate that Joaquin Phoenix might have been unavailable for some of the shooting period. But his “defaced” state is actually a highly original idea, because this reflects the fact that the blind Ivy must rely on her other senses to experience his presence. And it is precisely Ivy Walker, hitherto a capricious and flirtatious character, who will step forward as the unchallenged protagonist, carrying the rest of the film, with flying colours, one must say.

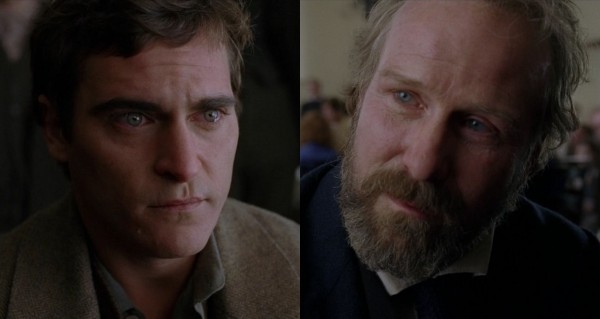

Lucius and Noah: Different types of love

Not only do Lucius and Noah both virtually disappear from the film, they do it with poignant and apt last words. Before Noah strikes with the knife, Lucius says “There are different types of love.” Afterwards, when Noah sits helplessly with blood-covered hands on his parents’ porch, he concludes his mutterings with “Mama.” Lucius having the night before discovered love with Ivy, and Noah being a big child, both words go to the core of the characters. (On the subtitles, there is a groan of “Oh, lvy…” while Lucius is writhing on the floor, but it is unclear whether it is uttered by he or Noah [who is moving his lips]. Since both love Ivy, the uncertainty is somehow fitting.) Ironically, it is the livestock massacre that Noah has secretly staged during Kitty’s wedding that will drive Lucius into Ivy’s arms, because their love scene comes about after Lucius has been hanging around her house to make sure she is safe.

Lucius is actually not alone in being fearless about the creatures, but Noah’s reason could not be more different: having seen through the elders’ hoax, Noah thinks everything to do with the creatures is marvellous fun. Furthermore, both Lucius and Noah are outsiders, they are lone children and say little. Noah is on the opposite end of the behaviour scale, however, totally frivolous, extremely extroverted and a great practitioner of body language and gestures (a collection is here).

Late in the film, virtually directly after the overhead shot of the dead Noah down in the pit, there is a cut to another overhead shot of Lucius’s sickbed. This is the situation mentioned in the previous chapter, the only time we are permitted to see Lucius’s face in the film’s second part. In this light, it is almost as if the death of Noah has caused an improvement in Lucius’s condition, or at least a signal of hope (or that Noah’s death has allowed us to again see the face that he tried to “erase”):

When analysing Ivy’s quest in the third article, we will see even more connective material between Lucius and Noah in the above situation. That article will also further explore various characters’ last words, to which The Village takes great care in giving poignancy.

Lucius and Ivy: The future of the village

Lucius and Ivy are two second-generation villagers who appear destined to be future leaders of their little world. They also seem meant for each other: Lucius is after all one of only two persons whose “colour” Ivy can “see”. Lucius plans to go to the towns for medicines to save others, but then Ivy is forced to complete this quest to save Lucius. Furthermore, they are the only villagers to be told “death stories” from the elders: Lucius hears of his father’s death from Alice; Ivy the stories of Mrs. Clack’s sister and of Edward’s father. (For the complete stories, see addendum C in the first article.)

They are also bound by some heavy-in-meaning dialogue. First via similar-sounding lines from the same man, Edward, about experience and innocence:

- Lucius is told: “You are fearless in a way that I shall never know” (Edward is moved and proud, since this means the project of the village, protecting innocence, has succeeded)

- Ivy is told: “It is a darkness I wished you would never know” (Edward speaks of the elders’ pre-village traumas of having lost their loved ones to violence, an experience that Ivy now shares, spoiling her innocence)

The other twin lines, first from Ivy to Lucius and then, in helplessly garbled form, from Lucius to his mother:

- Sometimes we don’t do things we want to do so that others won’t know we want to do them.

- Sometimes we don’t do things, yet others know we want to do things, so we don’t do them.

Ivy reveals she knows why Lucius stopped touching her in childhood (he fell in love with her, and it was somehow shameful). This helps him understand something he has long observed, that Edward never touches Alice. After she has told him the secret about his father’s death, he “retaliates” by telling her about Edward’s secret love for her. But since Lucius now knows that Ivy knows why he is not touching her any more, this knowledge makes him mangle Ivy’s words of wisdom.

Lucius is reticent and taciturn, Ivy is his opposite, vivacious and talkative. As mentioned, it is not until the very end of the second porch scene he finds his own voice.

Much of the second scene’s mood of quiet urgency springs from being shot as a very long take. At 183 seconds it is Shyamalan’s second longest, only beaten by the 229-second train seduction scene in Unbreakable. The current shot differs from that in its utter simplicity and the lack of camera movement (except for a softly intensifying track-in as Lucius touches Ivy on the cheek). The scene also appears to be designed to reverberate not only inside the film but also across Shyamalan’s filmography. It has big similarities to the conversation between the two brothers in Signs (“Are you the kind who sees signs, sees miracles? Or do you believe that people just get lucky?”). Furthermore, the first porch scene ends with a long speech by Ivy (about Kitty having “found love, again”, underlining that Ivy herself is now “free to receive interest from anyone who might have interest”), which is mirrored by the second scene ending with a long monologue by Lucius.

The Village is a film with lots of crying, but while Noah, in typical fashion, weeps uncontrollably, the most beautiful occasions are often of the precision type: Ivy’s lone tear at the most intense moment of the explanation scene behind the shed; her tear just before she lets go of the magic rocks in the quest sequence; and perhaps most beautiful of all, Lucius’s tear when facing Edward at the end of the second town meeting.

There are many more links between Lucius and Ivy: their already-mentioned chain of touching, and Lucius’s foray into the woods being a trial run for Ivy’s quest (to be covered in the third article).

Ivy and Noah: Twisted puppy love

Ivy Walker is a ravishingly beautiful girl who does not know what she looks like. She is sometimes coy and rather insufferable, however. (It is not clear whether Bryce Dallas Howard‘s otherwise flawless acting entirely nails her intended capricious tone.) In this mode she is often acting out several voices in mock conversations, which seems like an ironic comment from her, and the screenplay, on the fact that neither Lucius and Noah are any good as conversationalists. She also relishes throwing people off by sudden changes of topic, like in the second porch scene: “When we are married, will you dance with me? I find dancing very agreeable.”

When she lowers her voice, however, she seems to turn into another person. Several Ivy scenes go straight into the compendium of Shyamalan’s trademark hushed conversations, for example when she reveals to Lucius at the Resting Rock that she understands perfectly well his reasons for avoiding her. During the second porch scene, she follows up “No, I won’t tell you your color,” by descending into an almost inaudible, soft register, to say: “Stop asking” – the film’s most deliciously performed line, in a quietly electrifying moment.

Another great moment arrives when she is both commanding and pleading with her father to let her go on the quest. It sounds like some sort of terse poem, an official-sounding letter of intent, a plot summary for the rest of the film. It also offers a change in her tone of voice for virtually every line, as if Ivy is exploring her own thoughts while “reciting”, which happens with a methodical, clear pause between each “line”:

I ask permission

to travel through Covington Woods

and go to the towns

to retrieve medicines

that may save

Lucius Hunt.

Towards Noah, Ivy is dominating and commanding him around. It is fitting that her first line in the film, breaking up a fight, is: “Noah Percy! Stop your fussing right this moment.” But Ivy’s behaviour is in fact leading Noah on, letting him believe she is his girlfriend, sort of – even though she is only toying with him, for example when ordering him to kiss her cheek during the first quiet room scene.

This room is an arena for lots of meaningful structural business between Ivy and Noah (most of it already described in the hands and doors motifs of the first article). In the second scene Ivy is in a cold rage, slapping Noah as punishment for his murder attempt, thereby herself violating their mutual deal of “no hitting”. It was struck in the first scene, immediately followed by an echo: Noah wants to have a deal about “no cheating” during the footrace to Resting Rock. But Ivy shows her disrespect (playfully, but tellingly) by instantly breaking it – she tricks him to look away, then runs off to get a head start in the race. Here Shyamalan discreetly plants an indicator that Noah is not taking this as lightly: for a moment, we see a ripple of sadness and resentment cross Noah’s features. But then, like the child he is, as soon as he starts running, he just forgets about it and chases after her in happy abandon.

The cheating and Noah’s underlying desire for Ivy will of course reach a crisis during Ivy’s quest through the woods, which will be explored in the third article, in the process adding more links between Ivy and Noah.

Ivy and Mrs. Clack: Deadly resonance

Ivy and Mrs. Clack sit together before the start of the wedding festivities inside the pavilion. Both are in a buoyant mood. The older woman mentions that the bride, Ivy’s sister Kitty, reminds her so of her own elder sister.

Much later, when Lucius lies in the infirmary after the murder attempt, it is precisely Mrs. Clack, for reasons of resonance, who is delivering the bleak bulletin: “He has suffered a great deal. He may pass at any time.” Her look from the wedding is now continued in her sidelong glance at the embittered Ivy. It is not a watchful gaze any more, but the sad look of an experienced woman towards her former self and history repeating itself. Like she lost her sister to murder, she can only helplessly watch the cycle of loss and suffering replicate itself in Ivy. To make the identification and pain even stronger, in a metaphorical way Mrs. Clack and Ivy are sisters, since both had/has sisters who looked alike. (Kitty is even present, just beyond Ivy’s shoulder, our last glimpse of her in the film.)

Mrs. Clack’s gaze is the culmination of a passage of profound emotional resonance: first Ivy’s “Papa… I cannot see his color,” over Lucius’s body, her shaking voice blending in with the film music’s possibly most heavenly theme. Then as she is hauled away, the rawness of her screams is modulated into the soulfully pained exuberance of Hilary Hahn‘s violin, over the sublime shot of the receding line of four houses, indicating how Lucius’s life is ebbing away, then intertwining with Mrs. Clack terse, brittle voice of weary regret. Somehow all of this is now focalised into Mrs. Clack’s look, which in addition summons up her own strand of resonance, in its turn originating from a rather throw-away remark about her sister during the wedding. It is a moment not only of feeling but of stunning complexity, sweeping up whole networks of elements, the awareness of this vital for full poignancy – an excellent example of how intellectual reasoning can enhance the emotional experience of cinema.

There is one more thing:

Some sort of circular connective motion is at work here. To sum it up: Mrs. Clack sets it off by telling of her own sister’s murder during Kitty’s wedding, leading to Ivy’s protective embrace of Kitty, the deceased’s look-alike. Then not Kitty, but Lucius is assaulted, but the loss for Ivy is still similar to that of Mrs. Clack. Then Mrs. Clack enters the loop again by delivering the bulletin and the gaze. The circle is closed by the camera being lowered towards Ivy in a way reminiscent of the camera movement during Kitty’s wedding.

Ivy and Kitty: Sister as forerunner

The above situation is the reconciliation and “hand-over” scene where Ivy is assured by Kitty that any claims to Lucius have been relinquished. There is an “untold” story in this little scene, however. Kitty is shown as melancholy and subdued, the end point of a maturation process, compared to her childish first appearance declaring her love for Lucius to her father. There is now a strong contrast between the intense love Ivy shows for Lucius and Kitty’s earlier naive infatuation. Kitty realises that her love for Lucius was nothing compared to Ivy’s, and what is more important, she understands she will never experience this kind of love. For Kitty is now married to a rather unexciting guy and divorce is not likely to be an option in this extremely old-fashioned society. This is one reason for the undercurrent of sadness in this scene.

Another one is the scene’s subtle political aside about the strictures of an extremely rule-based society: the rules are made in the best interest of the villagers, who are by all means reasonably happy, but they will frequently prevent any deeper fulfillment. (Edward and Alice are another couple who have to quash deep feelings for each other.) Personal happiness is sacrificed for the greater good – a conservative attitude with stability as prime objective.

“One love to sacrifice another love is not right,” Ivy says to Kitty. The fact that the sisters speak of each other as a “cherished one” also reflects on Lucius’s “different types of love” to Noah. The sisterly love is the same kind of brotherly love Ivy feels for Noah. There is also a dramatic irony to the scene: Lucius is here “given” to Ivy, but since it comes directly before Noah’s murder attempt, Lucius is immediately taken away again.

It is now Kitty who comforts Ivy, but it was the other way around in their first scene (directly after Lucius has rejected Kitty), in the same location of the Walker house bedroom. The camera is closing in on the sisters in the last scene and retreats during the first one, creating a nice reversal. The movement in the first scene also indicates that Ivy will supersede Kitty in the narrative, since the mysterious never-before-seen figure ends up in visual domination. (The centrally placed hand plays into the hand motif and the strong contrast in colours of dress is also noteworthy.)

As the camera reaches the end point of its retreat, it reveals that the rest of family, keeping respectful distance, are gazing at the situation and the love Ivy shows for her sister. Is this an instance of the awe that Edward later in the film speaks about? (“The world moves for love. It kneels before it in awe.”) The lullaby Ivy sings for Kitty returns during the quest, when Ivy tries to comfort herself with it, abandoned by her escorts to the mercy of the sinister night of the woods.

Now follows a situation that goes to the heart of the attraction of Shyamalan’s cinema: an almost mystical connection between two points that seem completely unrelated but help bind the film into an organic whole.

The set-up forms a lyrical, highly complex rhyme with the film’s opening scene, with intricate criss-crossing patterns: A collection of people keeping their distance are contemplating a scene combining tremendous grief and deep love. In the far-away layer there are two characters: respectively Ivy and Kitty, and August Nicholson and his son Daniel in the coffin. Ivy comforts Kitty with a lullaby, August “comforts” his son (and himself) with some poem-like last words. And lullabies are usually sung for small children, like Daniel. There is also contrast: between indoors and outdoors, Daniel being buried (and forgotten) and Ivy being introduced (and eventually becoming unforgettable), and in camera movement: in the opening scene the camera is closing in on the scene of grief, in the other retreating from it. The slow pace is similar, however.

One minor but gratifying feature of this analysis process has been the emergence of Kitty as not simply a comic-relief character but as a forerunner in quite a few respects. Her total fearlessness – towards Lucius the fearless! – when “proposing” to him (her naivete and innocence make a refusal unthinkable) forms a nice contrast to the villagers’ dread of the creatures and, not least, Ivy’s traumatic quest. (Her hand movements seem designed to echo the “fear” game of the village boys.) Shyamalan has stated in the DVD extra material that he was fascinated by people embodying both innocence and a lack of knowledge and experience, and in reflection of this, Kitty’s version of the innocence the elders try to cultivate in their village laboratory seems to make her unprepared for life. Her innocence is caused by naivete rather than deep moral grounding as with Lucius. Kitty losing some of her innocence when observing Ivy’s love forms a parallel to Ivy losing part of her own, through Lucius’s coming predicament and her killing the creature during the quest. Finally, Kitty’s puppy love for Lucius forecasts Noah’s childish love for Ivy.

Even though Judy Greer was almost 30 during the shoot, she is utterly charming as Kitty, capturing her girlishness excellently. Placing her far from the camera in her first two scenes makes her look even more immature by reducing her size. One also wonders whether her gradually diminishing figure when talking to her father is meant as a signal of her not-so-good chances of winning Lucius. In the proposal scene she is larger, but still always kept in the distance.

Without making too much about it, there is also a tendency that Kitty is shown “larger” as the film goes along, as she is maturing – until we say goodbye to her, just after the reconciliation scene, in a close shot shouting “Ivy” after her sister when the latter storms off after the bad news about Noah. Kitty is as visually prominent during the wedding, which is an important moment of her maturation: she is taken aback by the intensity of Ivy’s embrace and Christop proves his inadequacy, totally oblivious to the significance of this incident, as usual just afraid that “She’s not going to squeeze my shirt like that, is she?” Maybe the track-in on her during the reconciliation scene could also be said to be part of this pattern?

Ivy and Edward: Unbreakable loyalty

Edward Walker is the de facto leader of the village, originator of the idea behind it, and master of ceremony at funerals and weddings. He projects an air of calm and composure, but during the impromptu council meeting by the infirmary where he announces his unilateral decision to break a taboo by sending Ivy to the towns, he shows the charisma and conviction that must have been instrumental in enlisting the other elders in this outlandish project.

Two scenes deepen our understanding of the Ivy-Edward relationship. Both are shot in long takes: their approach to “the old shed that is not to be used” (142 seconds) and the explanation scene (164 seconds) after its shocking revelation. In the first one Edward says: “You see light when there is only darkness. [An obvious reference to her blindness.] I trust you. I trust you among all others.” He also smiles proudly when Ivy confirms that she knows exactly where they are, so the scene has the added function of preparing the viewer for her excellent sense of orientation during the quest sequence.

In the next scene, even though Edward has to own up to the hoax – the acting makes him appear like a mix between a sheepish schoolboy admitting mischief, and pride in the cleverness of it all – their bond is so strong that Ivy immediately forgives him. These two scenes are very dialogue-heavy but the acting is so strong that monotony is avoided and plausibility achieved, both emotionally and as regards the often outlandish information delivered. Bryce Dallas Howard is compellingly distraught and confused. William Hurt, depending heavily on his expressive voice, convinces us fully about his warmth and benign intentions.

There is an intriguing family likeness between Ivy’s deliberate, pause-filled delivery of her “letter of intent” and Edward’s opening line at the infirmary meeting: “Ivy…has asked…to go to the towns…for medicines.” (He is also using the technique to some extent before the vote in the last scene.) Is this Edward’s normal way of dominating and controlling the pace of conversations, and is Ivy using it against him in the “I ask permission” scene?

Edward and Alice: The three stops of Edward Walker

While the relationship between Edward and Ivy is quite forthright, the same cannot be said about the Edward-Alice association. Especially their “It is all that I can give you” scene (above) is reminiscent of the Ivy-Kitty scene, quietly leaking subtext. Furthermore, both have to do with love: Ivy gets Kitty’s go-ahead, but the other scene is soaked in resignation and rejection – in bitter counterpoint to the link of passion that has been forged between their children.

Yet another inspired casting choice is Sigourney Weaver as Alice. She is fruitfully played against type, her screen persona as a tough-as-nails modern woman (or futuristic, in the Alien franchise), to which her sour appearance in the pre-village photo might be a nod. In The Village she occasionally comes across as someone trying a bit too hard to embody a friendly, wholesome, old-fashioned character, which is actually suitable for a film about modern people transplanted into a bygone era. However many times this author sees the film, it is impossible to suppress a delighted grin at Weaver’s slightly off-kilter, semi-goofy appearances (see below). But more often, her sharp, slightly gaunt features are perfectly suitable for tragedy, as we soon shall see.

The people Edward loves the most in the village are his daughters Kitty and Ivy, and Alice. (He is obviously fond of his wife but not on this level, and their three youngest, small girls play no part in the story.) His three loves are accorded three scenes, all shot in one take, with a singular mise-en-scène where the characters are performing marked stops three times, something that almost gives the scenes an undercurrent of ritual.

All of the scenes are also about love, and all contain declarations of love:

- from Kitty for Lucius

- from Edward about his own father (“He used to hold my hand as I hold yours. He taught me strength and showed me love” – the second stop happens at the word “love”) and indirectly for Ivy (“I trust you among all others” – here the third stop happens)

- unspoken, but very evident declarations from Edward and Alice for each other

The declarations are of an ever-intensifying nature: from Kitty’s puppy love, via the parental love in scene 2, to the shattering but silent ones between Edward and Alice.

There are also some odd links between scene 2 and 3: no. 2 ends with Edward about to open the door to the shed, and no. 3 starts with Edward entering the open door to Alice’s house (below). Furthermore, scene 2 ends with two characters in close proximity splitting up into two visual layers, and scene 3 starts with the exact opposite – even the compositions are basically identical.

This third situation, the “It is all that I can give you” scene, is possibly the most delicate in all of Shyamalan’s work. It seems simple but it is a deceptive simplicity. Thus it will reward us to examine it very closely to record all its subtle stages and elements. Further below every screen shot will be given with running commentary, but first the scene is presented in a slide show so that it can be observed in all its ballet-like flow of movement and facial expression (the show can be started from the beginning by clicking on the current image to enlarge it, and then return to the article):

Alice is doing all the emotion, Weaver’s sharp and thin features perfectly suited for pained grief and yearning. Edward is like a statue, almost all his expression coming through his voice, which William Hurt mysteriously manages to render studiously toneless and neutral, but at the same time quivering with passion. The scene is 68 seconds of unrelenting sadness, but Shyamalan and the actors hit the tone exactly right.

In the following walk-through there will also be some comparisons with earlier scenes, marked with red borders.

We shall finish the article by mapping out some context radiating from the Edward-Alice encounter to neighbouring scenes. Edward’s wording of “It is all that I can give you” almost seems to indicate that his gift is very small – even though it is Lucius’s life! – but in fact he risks everything (the destruction of the village) as he puts it in the next scene, the council meeting by the infirmary. Here Edward’s motivations for having sent Ivy are quite complex. Are his arguments a political manoeuvre to cover the fact that he did it for Alice’s sake, whom he has just left in the previous scene? It is not only Lucius’s desperate state that makes Edward break the rules, however, it is a deeper doubt, carefully prepared for early in the film during the funeral, where he is agonising about the death of August’s son. In fact there is a special connection between both the victims who are now weighing on Edward’s conscience, for as August says to Lucius: “I often wondered if you and my son bonded because neither of you is fond of speaking.” The medicine that Ivy has brought at the end could also be used to save the lives of others, alleviating the burden of children dying from illness. Like Edward shouts: “I cannot look into another’s eyes and see the same look I see in August’s without justification!”

Alice’s opening line: “I am making fresh cloths for Lucius. He needs them,” flows directly from the last line of the previous scene, the long explanation where Edward says to Ivy : “You gave your heart to this boy. He is in need. Are you ready to take this burden, which, by right, is yours and yours alone?” The link is cemented by the word “need” and the fact that Lucius is now both these women’s burden. The Edward-Ivy scene also has an air of being a heart-rending ritual (“Are you ready…”) where an experienced adult explains and passes on to a confused and distraught youth the burden of coping with the consequences of violence – as if inherited from generation to generation – and the burden of responsibility involved in entering such an intense love relationship. (“If he dies all that is life to me will die with him,” Ivy says earlier.)

There is another relation between the two women:

The most important context springs from the scene directly after Edward has hinted to the others about breaking the taboo of contacting the towns. Here Tabitha vehemently protests her husband’s idea: “You have made an oath, Edward, as all have, never to go back. It is a painful bargain, but no good can come without sacrifice. These are your words I’m saying. You cannot break the oath. It is sacred.” When Edward retorts: “It is a crime, what has happened to Lucius,” she answers: “You have taken the oath. You and the rest of the elders… Are you listening to me? You have taken the oath.” (Perhaps one could tie this to the other oath referred to, when Ivy says to Noah: “You needn’t go to the quiet room if you a take an oath to never strike any person again.”)

The scene serves to clarify a pivotal question, why Edward sends Ivy rather than going himself, but also what happens later with Alice. For here too there is a subtext. The “oath” can also refer to the oath of marriage, and the talk about “sacrifice” and the ever-increasing personal tone, with the final emphasis on “you,” might be an admonishment about keeping up their marriage. It is entirely plausible that on some level she has noticed, like Lucius did, that Edward’s love is directed somewhere else. Tabitha’s relatively minor role in the film is another indicator of the state of Edward’s marriage, and it is telling that her only venture into the limelight happens precisely in this scene. Her enormous emotional upheaval and eagerness when they finally embrace are also very revealing. By doing this, Edward has consented to sacrifice his love for the good of their marriage.

Like in the Alice scene, Edward’s female counterpart is doing all the emotion, while the camera position makes his facial expression barely visible. Contrary to a lot of other Edward scenes we have looked at lately, this one is almost entirely static both in character and camera movement, although Edward, perhaps tellingly, takes a small step forward, before the embrace. Also in these respects, it recalls the Alice scene, with its basically static set-up and his short steps towards Alice.

The conclusion of three scenes: the bleakness and physical distance of the Edward-Alice scenes are in stark contrast with the Edward-Tabitha scene, and also in the use of hands:

This article has attempted to collect everything to do with character traits and actions that, in addition to their obvious representations in the narrative, play out in the shadows of the film’s subtext.

The emphasis has been two-fold. How this is reflected in the mise-en-scène to make us feel that The Village is a lived-in organic world where we are not just commanded to believe in such traits but subtly perceive them. And how they are reflected in contrasts and similarities with other characters, to highlight these traits and actions.

*

Addendum A: References to other Shyamalan films

The usual themes and motifs: mentor characters, faith, finding one’s purpose, innocence, withdrawal from society are all prominent in abundance in The Village. Secrets as well (Lucius: “There are secrets in every corner of this village”):

- there is an entire community hidden inside the Walker Wildlife Preserve

- the elders’ secret about the time period the characters really live in

- their made-up lore about the creatures of the woods and the villager’s truce with them

- a number of sub-secrets of the latter: for example, the creature invasion was staged to instill fear in the villagers and smoke out the one that had breached the border; there are creature paraphernalia in a compartment under the floorboards of the quiet room and in “the old shed that is not to be used”

- the boxes all the elders have with hidden records of their past modern lives

- Edward’s secret love for Alice

- Lucius’s secret love for Ivy

- Ivy refuses to tell Lucius what his “colour” is

- Noah’s secret of having seen through the elder’s hoax and his secret impersonations of a creature

- Ivy’s secret towards her two escorts that the “magic rocks” are just make-believe

- Kevin’s secret from his boss of having helped Ivy with medicines

- Ivy’s “secret” deal with Noah: “You needn’t go to the quiet room if you a take an oath to never strike any person again.”

- Ivy joking about Mrs. Clack’s “secret” of having an elder sister

The background of violence and bleakness is maintained through the elder’s horrid recollections of pre-village murders. Their refusal to acknowledge the modern world out there is a metaphor of denial and at one point Ivy refuses to trust her own senses (“It is not real”) telling her there is a creature nearby. Children or childlike characters are present with Noah (and to some extent the very naive Kitty). Ivy panics during the quest and the village boys during their game at the border. The cellar-as-location motif is only fleetingly used, when the villagers hide during the invasion.

The following is a list of references in chronological order:

- The way a black branch passes over M. Night Shyamalan‘s name in the opening credits (and blotting it out) is similar to how a ghostlike shadow is passing over his name in The Sixth Sense.

- Two little girls splash water at each other’s dishes, while in Signs, during the same activity and with equal merriment, Morgan and Bo splash water at each other:

- Ivy is introduced in two stages (first mysteriously here, then stylised here), and something similar happens to Story (played by the same actress) in Lady in the Water:

- Ancient signs:

- The short glimpse of the creature running past below is very similar to a shot in Lady in the Water where Story is seen running, through a stairwell. Her flowing hair also strikes a resemblance with the creature’s branches on its back:

- The villagers hide in cellars and the creatures bang loudly on doors. In Signs the family hid in a cellar and the aliens banged on outer and inner doors of the house.

- The kneeling before a “child” we have already discussed

- The second porch scene is very similar to the conversation between the brothers in Signs (“Are you the kind who sees signs, sees miracles? Or do you believe that people just get lucky?”). They occur close to the films’ mid-points (Signs: at about 41 minutes; The Village: about 46), are hushed conversations between two characters, late at night, in darkened surroundings. Both scenes feature Joaquin Phoenix, consist of two lengthy monologues (although not a proper monologue, Ivy is clearly the driving force of her part), the latter performed by Phoenix, in both cases about the relationship to the other sex. In Signs it was a (very frivolous) story of an interrupted kiss, in The Village the kiss will happen, as conclusion to the scene.

- During this scene it is also revealed that Lucius holds the record of the “fear” game the young game. In Signs, Merrill (also played by Phoenix) holds several baseball records.

- The composition and content of these shots, with the same actress, from The Village and Lady in the Water have a related resonance:

Addendum B: Ivy’s “super-hearing”

Ivy is relying on heightened other senses to compensate for her blindness. Shyamalan signals that we are “inside” her sensory world by applying on the soundtrack a booming, echoing sound akin to a distorted bell. This happens on six occasions:

- when she is introduced, as she hears Noah fighting with the other boys and goes to stop it

- when the creature is closing in on her hand during the invasion (rather faintly)

- during the wedding dance, when before anyone else she hears the boys who come to warn the party about the livestock massacre

- when she is storming through the village on her way to Lucius’s house, after Noah has been found with blood all over him

- in the first shot of the quest through Collington Woods (a more subdued sound), when she sits at the Resting Rock, waiting for her two escorts to arrive

- during the quest, it starts when she hears the creature making a sound of something snapping (in response to her cane breaking), then she throws a stone into the bushes and hears the creature answer by throwing another stone

***