The Village, Part III: Love, murder and monsters

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the third article about The Village. The first one is here, the second here. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

At one point in The Village the Edward Walker character says: “I cannot explain in words.” Like many of the other articles in this series, this entry will take him on his word. The analysis will thus lean heavily on screen shots, preserving the film’s own gestures, often rearranging them in surprising combinations. Virtually every shot of the two examined sections will be shown. This may sound daunting, but in this film every shot is highly deliberate, every shot is counting, and many shots are made in long takes, greatly reducing the number.

The article will walk through two sections of The Village to discuss salient points, while sweeping up all sorts of connections to the rest of the film and other Shyamalan works. There will also be extensive references to items already covered in the first two articles. During the love and murder section, another objective is to track down various characters’ last words – which are all carefully judged and poignant – since the end of the section represents a turning point, after which several characters will virtually disappear from the story.

The film’s motif of wind/breathing was excluded from the general motif discussion in the first article and will be covered here as it is tightly bound to these two sections. The article will end with the quest through Covington Woods section. The material will thus slot itself nicely between the start and the ending of the film, which were covered in the first article.

*

In order to discuss the film properly, I will have to reveal the whole plot, including the plot twist at the end. The same goes for one important aspect of the ending of The Sixth Sense.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of The Village, here is a brief outline of the plot. There are several slide shows. Each show can be restarted from the beginning by clicking on the current image to enlarge it and then return to the article. There are also links to various points inside the other Shyamalan articles. Dependent on resources, on occasion web browsers will miss the exact target point on the first attempt, since images are loaded after text, which may cause a shift. If you do not reach the expected point in the other article, try again, then the browser will meanwhile have corrected itself.

The love and murder section

This section comprises the following scenes:

- The second porch scene, where Lucius finally declares his love for Ivy

- His mother confirms the village rumours about their new relationship

- Ivy makes sure that Kitty does not bear any grudge against her, since Lucius was Kitty’s former object of infatuation

- Noah, who is in love with Ivy, attempts to murder Lucius in a harrowing scene

- Noah is found by his parents all bloodied up on the porch of their house

- A brief scene where the council of elders are notified about the incident

- Ivy and Kitty are informed that Noah must have done something awful

- Ivy storms through the village to Lucius’s house

- Ivy finds him severely injured

- Mrs. Clack gives a bleak bulletin to Ivy and the villagers about his prospects

The first porch scene between Lucius and Ivy saw them discussing Lucius’s vague plan to go to the towns, and Ivy openly declaring her romantic availability now that her sister Kitty is about to be married off. It took place just before the creature invasion, when Lucius saved her from an approaching red monster. (It is easy to misplace that event: Ivy does not stand on the porch – although there is no establishing shot, a house can be seen through the doorway, proving that she is on the opposite side of the house, facing the village.)

Their second porch scene, the point of departure for the current analysis, starts the same night as the livestock massacre that interrupted Kitty’s wedding party. Ivy suddenly wakes up to discover that Lucius is guarding her house. (The two shots leading up to the scene can be seen here. There are more stuff about the porch scenes in the second article, in the “Lucius and Ivy” chapter.)

Here Lucius concludes a long, impassioned monologue with an answer to Ivy’s impertinent question just before: “And, yes, I will dance with you on our wedding night.” (In poetic irony, this will be his last words to her in the film.) But they have actually danced together before:

Becoming aware of the echoes of their previous dance-like moments creates some form of structural poetry. Without thinking about the film in terms of structure, we would have been oblivious to the extra resonance conjured up by their dialogue – intellectual activity leading to emotion.

The ending of the film echoes its beginning, like many stories do. But Shyamalan takes this further, in that many story arcs (for example the guard Kevin’s appearances being book-ended by meaningful sounds), scenes or shots will follow the same strategy. Thus, the current scene will soon fold back on itself, picking up its initial set-up and turning back to the porch from where it came.

These two past scenes are connected through the colour and lighting scheme, and being about caring for and comforting others in distress – Ivy sings the lullaby for Kitty, who is heartbroken from unrequited love; Lucius helps August, who is grieving over his dead son. Here Ivy and Lucius were confined to separate scenes that still were connected through the other elements, but in the porch scene everything fully converges: characters, music, even their bodies, for Lucius leans over to kiss Ivy:

Let us stop for a moment to wrap up how actions, characters, plot elements and dialogue combine to create a complex strand with meaningful echoes. Two moments directly follow each other and are obviously linked: (1) through Ivy’s crying and Noah’s crying, tears of respectively joy and despair; and (2) through puppy love: Kitty for Lucius (in the past, now overcome) and Noah for Ivy (raging still, out of control).

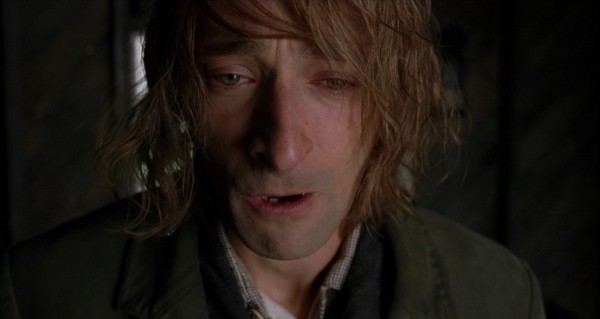

Furthermore, when Ivy threatened to put Noah in the quiet room earlier in the film, he said: “I’ll cry quarts.” When Ivy is soon told about the murder attempt, the messenger says: “Noah Percy was found with quarts of blood upon his clothes and hands.” After the murder attempt, Noah’s parents find him on the porch, crying, with blood all over him. In the murder scene, Noah will keep on blinking back tears, for example during the first knife strike. The recurring crying and other echoes as well as the odd vocabulary (a quart is an old-fashioned measure of unit) help create a web of interconnectivity, as if events are being played out according to a preordained, inevitable scheme.

It is hard to describe the immensely powerful simplicity and truthfulness of this scene – it is as if one sees the tragedy of being alive unfolding for the first time. It is all accompanied by one of James Newton Howard‘s many instantly memorable themes for this film, with Hilary Hahn tearing into her violin, furious and elegant at the same time.

This is one scene of The Village where it also pays to know the geography of the place, or else one risks being denied full resonance. For the house he is looking at in the beginning, and all along scrupulously maintained in the background, is the Walker house, where Ivy lives. (Shyamalan used backgrounds to particularly subtle effect in The Sixth Sense.) It is soaked in the sun, while Noah is now forever confined to the shadows. At the same time, the contrast to other porch scenes, the two Lucius/Ivy night-time situations, could not have been greater, also in Noah’s utter loneliness versus the others’ intimacy.

The house Noah looked at is also the building where the sisters have had their reconciliation scene, in fact they will soon come out of the door (after a brief scene where the council of elders are notified about the incident):

Ivy storms off towards Lucius’s house, accompanied by the booming sound on the soundtrack that always signals Ivy’s “super-hearing” and heightened senses being applied at full steam. “There are whispers all over the village,” said the lady that morning about the rumours of romance, but now there are shouts everywhere (“Is there anyone injured in here?”) – contrast reigns again (Cries and Whispers?).

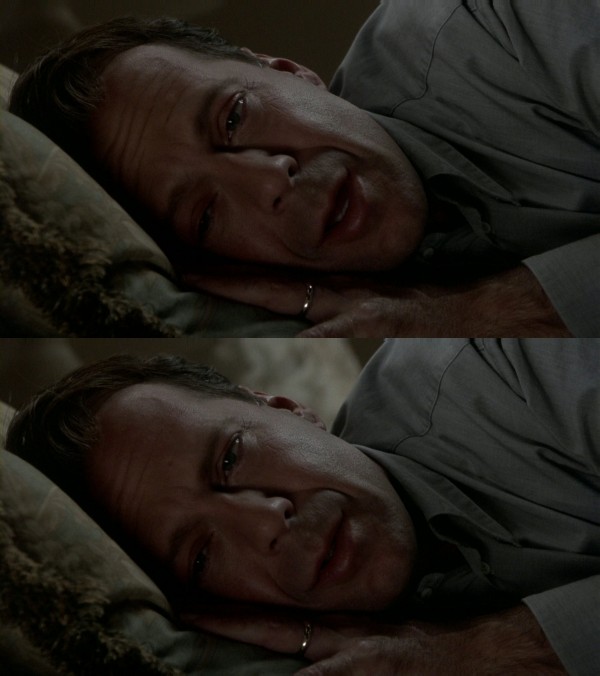

Seen in the following slide show, Ivy’s journey is staged as if she leaves civilisation, for people and houses are falling away behind her. (This could actually be one reason for the relative isolation of Lucius’s house: providing an empty background and a distance for Ivy to walk.) Her world right now is only Lucius, whose house at the end will tower over her, laden with importance. In fact, the scene both ends and starts with looming buildings, the town hall and Lucius’s house. The 56-second continuous take is shot from a very low angle, reminiscent of the final shot of the murder scene (and upcoming scenes inside the house), as if Ivy is metaphorically seen from Lucius’s point of view, as he lies dying on the floor.

Ivy here decides to punish Noah, who is currently imprisoned in the quiet room. In the first article, we spoke of a set of visual rhymes in connection with the two quiet room scenes. But there is one more:

The situations form some sort of relay. In the murder scene it was Lucius inside and Noah outside. In the quiet room scene it is Noah inside and Ivy outside. She is the next “murderer” and will enter to physically attack him. (For more about the quiet room: here and here.)

Wind, breathing and flapping flags

The motif of wind runs like a subplot through The Village, and becomes very important in the next section to be analysed: the quest through Covington Woods. There wind will be heavily connected to breathing, something that is echoed in the film’s closing seconds where Lucius’s breathing sounds like the wind. So let us have a look at some earlier wind occurrences, and then catch up on its usage in the love and murder section. It is applied in highly deliberate fashion, both visually and through subtle manipulation of the soundtrack, with specific results in mind, both in mood and motif coherence.

The conditions in the valley of the village are very windy, as can be seen in many scenes (for example here). Just watch how the wind torments Ivy’s hair above – it is also clearly bending trees in the background of this scene, so it is not simply due to wind cannons – the weather adding immensely to the feeling of fatefulness of the situation, with Lucius close to death and Edward’s heavy voice saying: “The moment I heard my daughter’s vision had finally failed her, and that she would forever be blind, I was sitting in that very chair. I was so ashamed.” Below, just afterwards, having arrived at the old shed, the wind augments her look of sudden vulnerability:

Wind can be heard over M. Night Shyamalan‘s credit before the first image of the opening scene, quite natural since it is very windy during the funeral. We also hear a faint sound of wind when the medicine cabinet door is opened in the guard shack scene. Considering the wind over Shyamalan’s credit, this is logical since in that very moment his face (because he is playing Jay, the head guard) becomes visible as a reflection in the glass door. It is also fitting since the medicine is for saving Lucius’s life, and wind is connected not only to death but to him during the film. Just for starters, precisely when Kitty mentions his name when talking to her father (here), a gust of wind is heavily emphasised on the soundtrack (and in this case, maybe visually reinforced by cannon?).

Although conditions are not particularly windy in the Resting Rock scene, the sound of it is very delicately used as a subconsciously mood-enhancing device. As soon as Noah has run off, Ivy and Lucius start to speak intimately (“I know why you denied my sister”), and the wind immediately makes itself subtly felt on the soundtrack, causing leaves to rustle, adding further cosiness to the sunny weather. It also beautifully complements Ivy’s suddenly lowered, soft and warm voice.

Then there is an increase in wind as he says his first line, “You run like a boy,” and when he looks at her, the sound increases considerably, then again, to a mild crescendo, as she presents her memorable aphorism, “Sometimes we don’t do things we want to do so that others won’t know we want to do them.” Then it quietens markedly when Noah returns, spoiling the intimacy of the situation. Since Ivy experiences the world to a large extent through sound, using audio effects is logical to draw us into her world.

Although “inadmissible evidence” but indicative of the screenplay’s importance on wind, the fourth and very interesting deleted scene on the DVD shows that there is an instrument in the woods that is producing the far-away creature sounds, to such unsettling effect on the villagers, and it is driven by wind. There is also a little whirlwind beneath it.

Catching up on the windy business during the love and murder section, it makes its mark at a very appropriate moment in the porch scene:

In Lucius’s house a whistling sound of wind becomes a recurring signature. (In the late “It is all that I can give you” scene between Edward and Alice it comes, like an announcement, right at the start.) Its initial appearance is in the murder scene, just after Noah has knocked on the closed door, as if an ill-boding signal of the coming violence. Then it subsides in a “quiet before the storm,” only to triumphantly return in a new development, a “whooosh” of wind, as Lucius looks down at the knife in his body.

We can see behind her, to the left, that the other door is open (for a clear look at it, see the “It is all that I can give you” scene), so there is a believable draught to cause all the wind (because it was heard even before Lucius opened the main door to let Noah in).

As we shall see, the flapping of curtains and flags creates a symbolic progression, hidden in otherwise prosaic, naturally-occurring events. The curtains are carried forward into the soon-to-come scene where Ivy stands outside the infirmary, see the following slide show:

She stands like a statue while the camera is closing in with intensifying power. The big flag in the wind magnifies the curtain effect at the murder scene, both in size (when Lucius fell) and in sound (when Ivy found him). The insistent flapping, the flag’s wild movements, the fact that it often obscures her completely, express the upheaval inside her mind. The way the camera itself is moving through the flag immerses us in her inner process. (The pole and flag have a very similar colour as her skirt – a blending of objects and person?) The flapping is also a reminder of the moment of finding Lucius’s body, the memory burning inside Ivy more and more. In this scene we see once more how sound is ideally suited to represent the workings of Ivy’s mind, since aural information is so central in her perception of the world.

The scene is all about transformation, both in the meaning of the symbol and in Ivy’s psyche. While in the murder scene the curtain symbolised Lucius’s life force blowing away, the powerful sounds of the flag represent her willpower and hardening decision to act, and act forcefully. In the next scene, she will enter the quiet room and repeatedly slap Noah with brutal and deliberate force. Then the girl who earlier dreaded the forest (“It is putting knots in my stomach”) will with steely resolve virtually demand of her father to let her travel through Covington Woods to get medicine for Lucius.

At the outset of the quest, yet again a flag is awarded fetishistic attention and again there is a transformation, now Ivy overcoming her fear:

We are ready to enter the woods.

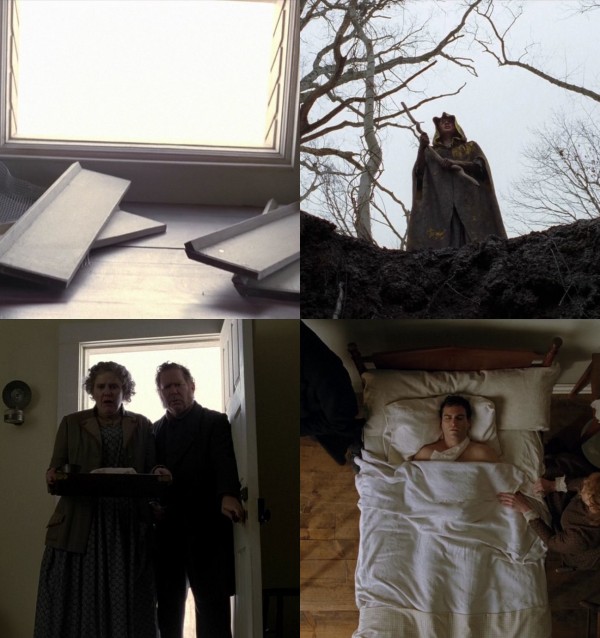

The quest through Covington Woods

The start of the quest marks a monumental turning point in the film. Most of the action will now unfold trapped inside a desolate landscape, drained of colour, allowing feverishly bright-coloured figures to stand out as archetypal properties or elemental forces. The tone becomes obsessive, reinforced by the presence of characters who are unable to go into the woods unless they wear special clothes, as if they are governed by overwhelming neurosis – or as if they enter new personas to act out a medieval-looking ritual. It is a ceremony marked by serenity and calm, however, where the drama is kept smouldering below the surface. The hypnotic, ritualistic nature of the quest sequence is solemnly announced by a peculiar, stylised staging of the players’ first appearances. The last moments before they enter the woods are accompanied by doom-laden, blaring orchestral music, which is pushed over the edge into a modernist, frenzied piece as the border is breached.

Lucius’s earlier short foray into the woods is a trial run for Ivy’s quest. He sets out, in a yellow cloak, finds berries, encounters a creature, then returns to the village. As Ivy later will echo when she suspects a creature nearby, Lucius takes off the hood before entering, signalling to the creatures that he is pure of intention, not afraid, and also not hiding anything – unlike the rest of the village, he has no secrets. Considering this parallel, it is not surprising that there is a network of echoes between Lucius and Ivy (in addition to all the links between them described in the second article):

When Ivy appears in the first shot of the quest, it is a virtual re-introduction of the character. She looks like a new person in the peculiar cloak, about to embark on something that hitherto was totally alien to her, as afraid of the woods as anyone. But the parallel with Lucius abides:

The current scene and the Resting Rock scene (with Ivy, Lucius and Noah) are among the few where three characters are present, not pairs, fours or eights as usual. As we learned in the first article, this character count indicates dysfunction, and soon enough, the quest party will disintegrate. There are more similarities: in both situations the person sitting on that spot is the first one at the scene, then two others are added, one by one (in the Resting Rock scene Lucius was the first, then the footrace brought Noah and then Ivy). Playful casualness is now replaced by procession, however:

With their faces now revealed, it turns out that the choice of Ivy’s escorts has been most unfortunate. Finton Coin suffers from deep-rooted anxiety problems but hides it from the village, and Christop Crane, even though now Ivy’s brother-in-law, is the cowardly and utterly prosaic counter-mirror image of Lucius. (More about fear and the two escorts’ personality in the second article.)

After (as seen before) the equally ritualistic presentation of the “magic rocks” to the forest, the shot of the flag, and the slow track-in on Ivy looking into the camera…

When they enter the forest, the strange atmosphere is maintained by an overhead shot, which also underlines the entrapping effect of a latticework of branches, forming a spidery web over them. One characteristic of The Village is that even very simple-looking shots turn out to have hidden complexities. Thus, as Ivy enters the shot, the focus is initially on the overhead branches, gleaming sharply, but focus is later racked to concentrate on her. At the same time the camera is moving laterally to the left (to slow down the pace by keeping her in the shot for a longer time?) but coinciding with the focus change, it is descending a little towards her:

Below, we see that Ivy leaves the shot entirely before the next character enters. This fragmentation indicates their tenuous solidarity and foreshadows the coming disbandment. The distance between characters and their one-by-one appearance recall the dazed confusion emanating from the stylised shots in the aftermath of the livestock massacre:

Soon a tense shot/reverse shot construction arrives, the quest balancing on the edge of disintegration. But first (the below slide show) there is another “fragmented” shot, with Ivy alone, before Finton overtakes her to point out a problem:

The Village, and the quest in particular, becomes such a singular experience due to Shyamalan’s ability to blend a remarkable sensitivity – as with Ivy above – with a relentlessly imaginative staging.

The Village kicks off the next shot with an inventive aural idea, a kind of “cutting on sound effect”: Finton speaks Ivy’s name as if placed inside a ghostly echo chamber. Here the film again seems to play on Ivy’s blindness, the sound effect reminiscent of the booming that accompanies Ivy’s “super-hearing”, as if Ivy is lost in thought with Finton’s voice waking her up to reality. Now it is time for another acting tour de force from Bryce Dallas Howard, with Pitt’s cherubic face in fine support. As not long ago, they form the leader/submissive diagonal. Finton takes Ivy’s hand, holding on to it for a long time, and puts the bag of “magic rocks” into it, while explaining that he cannot go on: “You will be safe. They will not harm you, because you cannot see. They will take pity on you, the way they took pity on Noah when… when he ventured in the woods. They will kill me, lvy. I cannot stay.”

What is going on? Ivy unceremoniously discards the very stones providing her safe passage? Confusion reigns for the first-time viewer.

Tear is falling, stones are falling, masks are falling, for the film is about to enter “the old shed that is not to be used”. During an extended flashback we learn that everything we knew about woods and creatures is an illusion. We pick up from where we left earlier, outside the mysterious shed: beginning with the reveal of the hidden red cloaks and creature paraphernalia, followed by the long explanation scene, the “It is all that I can give you” scene between Edward and Alice, and the impromptu council meeting by the infirmary. Here Edward eventually persuades the others to accept sending Ivy to the towns.

These three shots establish a new day, a “quiet before the storm” mood (there is even no wind in the woods, for once), have a narrative function (Ivy’s father told her to follow that stream), and also represent sounds that a blind person will rely on. They might also conjure up a false sense of security (peacefulness, no creature attacks) and absence of conflict (no cloaked combatants reflected in the stream). But out of nowhere crisis arrives:

Is there a plot contrivance here? When encountering a hole the most natural thing would be to take a step backwards away from it. But in order to be in a position to arrest her fall with her hands, she had to be turned in the other direction when falling. Maybe she simply did not understand that it was really a large pit? Contrived or not, it sets up a brilliant scene:

We ache to see how Ivy is doing, but the camera seems to have a will of its own, torturing us by holding back information. Eventually it begins to slide towards the pit and when the majestic, sinuous movement starts to look down into it, the hole seems dark and bottomless. But suddenly something yellow can be glimpsed, and it is gradually revealed that Ivy has managed to cling to the steep wall. Shyamalan is never satisfied with the simple, however, because now there is a flourish: the camera is rising up into the air a bit. This has an almost subliminal effect: she seems even more lost, as if the camera refuses to help her, merely toying with her.

When she touches the root her head is cut off by the framing. When she feels her way around the pit (above) the hood covers her eyes (in decidedly unflattering fashion, she looks almost demented!). All of this conforms to a strategy of making the viewer implicit in her blindness. When her escorts were still around, Shyamalan eagerly shows her face, even in many bold close-ups, for example during the leaving of Christop (here) and Finton (here), not to speak of her stare into the camera (here). But on her own, without the eyes of others, she is truly blind. As soon as the film returns to the quest from the flashback, when in the lullaby scene the camera leaves her to be swallowed up in the darkness and spidery wood, it is not only a goodbye to dialogue, but also a farewell to her face. Thus, two five-second glimpses of her half-obscured visage, when she grapples with the pit, are the only views of the face of the protagonist of The Village for slightly more than two and a half minute. (But we have not seen the end of it yet.)

When she touches the root her head is cut off by the framing. When she feels her way around the pit (above) the hood covers her eyes (in decidedly unflattering fashion, she looks almost demented!). All of this conforms to a strategy of making the viewer implicit in her blindness. When her escorts were still around, Shyamalan eagerly shows her face, even in many bold close-ups, for example during the leaving of Christop (here) and Finton (here), not to speak of her stare into the camera (here). But on her own, without the eyes of others, she is truly blind. As soon as the film returns to the quest from the flashback, when in the lullaby scene the camera leaves her to be swallowed up in the darkness and spidery wood, it is not only a goodbye to dialogue, but also a farewell to her face. Thus, two five-second glimpses of her half-obscured visage, when she grapples with the pit, are the only views of the face of the protagonist of The Village for slightly more than two and a half minute. (But we have not seen the end of it yet.)

When Ivy realises that her cloak has become so muddied that the yellow “safe colour” is likely to be obscured, her fear of the creatures, drilled into her for decades, returns. Even though her father assured her it is a hoax, he also said that originally “there did exist rumors of creatures in these woods.” So she frantically attempts to clean the cloak with her hands.

The next few minutes are a study of claustrophobia in open terrain, a tour de force of sustained use of limited viewpoint, staged with a virtuoso feel for nightmare.

During the game the village boys play to see how long they dare stand with their backs to the dangerous forest, Jamison says: “They made a sound when I made a sound,” after his fearful gasp has been answered with a groan from the woods. This seems to be a clever aspect of the elders’ made-up creature lore: before a creature attacks it will imitate its victim. This will function as a warning so the villagers can get away before any attack – thus there will never be a need to actually harm anyone.

Without stating it clearly at all, what happens to Ivy now subtly plays on this seemingly throw-away information. She is not just scared by a sound, there is a specific reason: a creature is signalling that it is ready to attack. Like a lot in this quest sequence, the specificity of the actions is clear to viewers who are very attentive or have familiarised themselves with the film. To others, the general eeriness of the atmosphere will still make the essence of the threat come across.

Let us backtrack a bit. Since we had never seen a creature clearly before (our best look so far was here), it was not easy to realise that its first appearance to Ivy was with its back to the camera. (And, by all means, not necessary – in fact, its indeterminate shape simply added to the strangeness!) Now that it has stopped in an identical position, it is obvious. But before (see below), one could well assume that the central bunch of bones was appended to arms clutched together on its front, and that the branches on its top was fastened to a reclining head. But with its positions clearly understood, we can now also realise that it is methodically turning towards Ivy with a 90 degree movement for each of its three appearances, as if part of some cruel ritual, or “nightmare logic”:

Its geometrical way of moving joins an entire system of frontal/profile shots in the film. It has been described in the first article, but let us sum it up through the following slide show:

There is also a second underlying pattern here. When Ivy broke the stick and threw the rock, we explained how the creatures follow a pattern of miming the humans’ actions before they attack. This was subtle enough in the first place, but nothing compared to how it is reflected in the creature’s further actions. In fact, everything the creature does in its visual appearances is aping Ivy’s behaviour:

- 1st appearance: Ivy stands with her back to the camera, then turns to find the creature with its back to her. So, before she turned, the creature was aping her position. It is even shifting its weight from foot to foot, like we saw Ivy do here.

- 2nd appearance: Ivy stands behind a tree, then we discover that the creature is doing the same.

- 3rd appearance: Ivy stands with her back to the camera, then turns to find the creature facing her. So now their positions mirror each other, but the creature was one step ahead – which is perfectly (dream-)logical since it is about to attack.

All this (sadistic) playfulness on the part of the creature dovetails beautifully with the fact that it is impersonated by Noah. Even in the new gruesome incarnation, his personality aspect of being just a big child still shines through. The fact that he seems to have taken the rules of creature behaviour to extremes fits with him being an über-creature, a murderous usurper of the hoax, who has even augmented the outfit with more bones and branches. Finally, Noah will even be aping, extremely unintentionally, Ivy’s behaviour by falling into the pit!

This strand is so smart, playful and ironic – and all hidden. The entire aping subtext that explains the specific reason for the creature’s odd behaviour is solely activated by Jamison’s seemingly throw-away remark during the “daring game”. (Two other important plot points are repeated during the quest through Edward Walker voice-overs, but in this case we are entirely on our own.)

Ivy herself also contributes to the weirdly repetitive nature of events. She is turning around thrice, each time strongly emphasised by dizzying camerawork, and she too conforms to the “90 degrees rule”: when hearing the twig snapping (90 degrees, here), on the creature’s first appearance (180, here), and its third appearance (180, here). It is also tempting to draw a connection to all the turnings at the early stage of the quest: physically (here), as a motif when Christop moves in a way recalling the 90-degree pattern (here), and in plot, because both Finton and Christop will turn around and go back to the village. (One also recalls the amusing “turning points” in Unbreakable.)

Why is all this important? Because nightmares are often crammed with strange repetitions, grinding on and on, with no apparent reason other than “dream logic”. In combination with the film’s sluggish pace, the activation of the above patterns simply reinforces our experience of the quest as nightmare, a horrific version of the heavily rule-based village life. (We should also remember that the blind Ivy cannot grasp the full impact of Noah’s aping, so that strand is mainly included for the benefit of us, the viewers.)

It is very convenient, then, that there is also a third hidden pattern. The creature appears in three different positions within a long take, creating an odd link to the staging of three long-take scenes with Edward Walker, where he stops thrice:

The two other scenes are Edward and Ivy’s approach to “the old shed that is not to be used” and his “It is all that I can give you” scene with Alice (both described in the second article). Edward is also the protagonist of another curious creature-related item:

The creature is an illusion, a reflection, a hoax created by Edward and the elders. Editing, framing and character movement seem here to be designed as an early subconscious clue that the elders are playing the creatures. Edward and the creature sharing the “three-stop strategy” is another undeniable connection, but could it mean something more? One is almost tempted to speculate that these things might be infinitesimally subtle misdirection, planted in the subconscious of the viewers to make them suspect that during the showdown with Ivy, the creature is played by Ivy’s father there as well.

Back to the action, and back to square one, so to speak, since the creature now apes its first appearance, with the back to the camera:

Now one of the film’s most inspired ideas is introduced, as simple as it is brilliant: cut-aways to the forest will regularly appear as a lyrical running commentary to the action, a Greek choir observing events too horrendous for words.

The chaotic “tribal” music of the chase is suddenly supplanted by a serene, harmonious piece. Also this has an equivalent in the “dance” of the creature invasion scene, where the uplifting, melodious main theme of the film music occurred for the first time, celebrating not only their safety but also that they touched each other for the first time in the film. In the woods, Ivy is back at the pit, which turns out to be exactly what she needs to battle the creature. In the Walker house (above), we see the open trapdoor to the cellar, another “pit” that means safety from a creature, into which they retreat as a shelter.

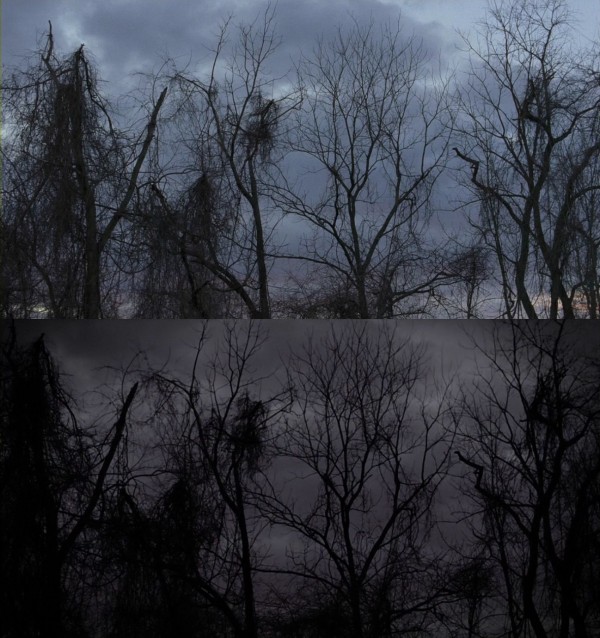

Ivy is suddenly seeing the whole picture, but why? What is happening here? Let us begin with a look at the film’s moody title sequence:

The title shots paint the trees as disembodied, abstract entities. Their extremities look like a network, like the interconnected synapses of our brain. The woods of The Village are an embodiment of our primeval fears, an irrational place where creatures are lurking, waiting to tear into us. The fear of them governs our lives. Like the village is encircled by the forest, we are completely surrounded by these threats, and it is unthinkable to venture out into the woods. The camera of the title sequence is gliding around in ghostly fashion, its gaze up into sky, the branches looming over us, making us feeling trapped, suffocating us.

In the early stages of the film, inside the village itself there are many lone trees that are bare (for example, in the background here), rather inexplicably since the woods are still richly foliaged. Do they foreshadow what will come during the quest? Because the spidery webs of the title sequence are clearly transplanted into the woods at the time of the quest: foliage-free trees, the forest as a barren wasteland, shots constantly conjuring up tangled webs (for example here and here) and even snake-like protuberances (here). If the woods are a metaphor of our own brain, it is a deluded mind, since the threats that make the villagers cower turn out to be imagined. Evil is not an external threat but springs from something inside us. In order to heal the brain of the village, it needs to be purged of its irrational fears. Therefore it is “logical” that Ivy should be able to connect to the forest, to become one with it, so that she can destroy its own invention: the creature, the brainchild of the village.

In this interpretation, drawing a connection between wind and breathing, which we have already touched upon, is especially useful. Ivy’s breathing is accentuated heavily during the quest, for example when she is hyperventilating before she is revealed as entrapped in the red field. During the final chase she is breathing heavily, especially in this shot. She is also constantly waving her hands as she runs, and this can be linked to the cut-aways of the trees: they are blowing in the wind (breathing), waving their own extremities, the branches. So there is already an alignment between Ivy and the forest: they breathe and wave together, as one.

This alignment reaches its climax when she is reconnected with the tree root. It is like a handshake with the forest itself. At a prosaic level, she simply recognises where she is and gets the idea to trick the creature into the pit. But on a metaphoric level, all the aspects that suddenly kick in – the calm, the serene music, the wide shot, the parallel to Lucius and Ivy’s first, all-important emotional breakthrough when touching each other – point to a new level of understanding. (In Shyamalan’s next film Lady in the Water, alignment was again important: it is said that “the world will line up and reveal we are on the right path, that the universe will give us signs.”)

The tree root had been in the ground for a long time, so it represents the woods, its subconscious, its wholeness. In this metaphoric reading, the tree has uprooted itself, to help Ivy, so the creature can be killed. Without the pit Ivy would not have survived. Her falling into it was also necessary, so that Ivy could learn how to put it to use later. She managed to get out, and now she is about to get a reward from the woods.

Like Edward said in the discussion among the elders: “The world moves for love. It kneels before it in awe.” The forest is kneeling before Ivy now, because it understands that she is pure of heart. (Noah’s own innocence, on the other hand, has been corrupted and his creature outfit is stuffed with branches, skins and bones, but unearned, “stolen” from the natural world.) The woods will help Ivy kill the creature, so she can free the villagers from their self-imposed prison, the imagined threat of monsters.

Alignments stretch further than just the woods, however. For now Ivy gets her wish: “I do long to do boy things, like that game the boys play at the stump. They put their backs to the woods, and see how long they can wait before getting scared. That’s so exciting.” Like the boys, she now must control her fear, or else she will jump away too quickly. The current situation is also a variation on her outstretched hand during the creature invasion – which in itself was a variation on the game: how long would she dare stand there in the doorway?

The connections to the game and the invasion are quite subtle, however, because of the very different circumstances, differing shot compositions and the nightmarish whirlwind of developments we have been subject to during the quest. (The situation also fits in with the ubiquitous hand motif, of course.)

In the last three shots, we have seen in succession the film’s three major characters – as if taking stock of the narrative – in a rhythmic way of the camera looking down (at Noah), up (at Ivy) and down (at Lucius). There are also a lot of whispered echoes in this small slice of film:

Is the whiteness that engulfs Lucius, like it does the survivor Ivy (who will get the medicine to save him), a foreshadowing that Lucius too will pull through? This might be another reason for the sudden reappearance of Lucius’s face, and the camera sinking down towards him. Edward Walker just said: “His will to live is very strong,” and the way everyone else falls away and the increasing emphasis on his face indicate that it is Lucius’s reserves of individual strength that will keep him alive until Ivy returns:

There is another heavy-with-meaning rectangle in The Village, also this observed from above, in the second shot of the film:

Like the pit, it is connected with darkness, death and the demise of someone’s child (and Noah is just that, a big child).

M. Night Shyamalan has a final flourish up his sleeve:

There are numerous overhead shots in the film, but these are the only ones that are combined with this ultra-stylised camera movement of descending straight down from the heavens. Here there is an especially striking contrast since August’s face is turned away. In fact, we are never allowed a proper look at anyone’s face during the funeral ceremony (this is the closest we come).

It is indeed a strange juxtaposition: a face that has been hidden for ages against a scene where faces are hidden..! (The “hopeful” white rectangle of the bed also becomes meaningful compared with the dark grave.) The worried elders around Lucius’s bed fill the roles of the onlookers during the funeral, and the camera position hides their faces, just like with the funeral gathering:

There is also a similar sense of anguish, in both cases a parent grieving over a son’s situation. Finally, there is a personal link, since Lucius is kind of a substitute son to August, as the latter once said to Lucius: “I often wondered if you and my son bonded because neither of you is fond of speaking.”

Having thus cast the net back not only to the opening scene but the initial shot, we end this particular examination of The Village.