Joachim Trier’s Thelma, Part I: What does it all mean?

This article contains BIG SPOILERS, both in words and pictures. If you have not yet seen Thelma, it is recommended that you return to this article at a later time.

The screenshots from Thelma in this article come from a screener made available by the film’s producer. (This is the first article on Thelma. The second article looks at motifs and visual ideas. The third article is a close analysis of the epilepsy test sequence.)

*

Zeitgeist is replaced by timelessness, chamber music by a symphonic work. The systematically unpredictable Thelma is Joachim Trier and his team’s most sonorous, lyrical and adventurous film.

Thelma is seductive and musical in tone and construction. The imagery is more expansive than in Trier’s earlier feature films, which leaned towards dialogue and realism, marked by visual restraint. Thelma looks more like his early shorts, augmented by a new artistic maturity, experience and technique.

Trier’s trademark facial chamber music is less prevalent here, his first work in CinemaScope, but it rings even more beautifully in Thelma‘s more varied landscape. The new film also has a far broader and more detailed use of visual motifs.

Thelma‘s range is impressive, from intimate humanism and lyricism, to symbolic sequences, melodrama and flamboyant set pieces. Its very enthusiastic reception by both critics and audiences in Norway is not surprising. A recurring sentiment is that people say they cannot stop thinking about it; one of the author’s Facebook friends compared the experience to witnessing a whole life of feelings and associations. One exciting aspect of Thelma is precisely how it is constantly expanding its reach, taking us to new spaces, genres and moods.

Thelma’s supernatural powers can be said to comment upon a topical issue. Today many create their own reality by clinging to certain beliefs (conspiracy theories, rejections of robust science) and Thelma’s denial is so strong that she can actually change the physical state of the world. Through Thelma‘s link between the heroine’s abilities and her sexual orientation, towards the end it also becomes a powerful metaphor of “curing homosexuality”, a nasty practice quite widespread in fundamentalist religious circles. As a whole the film is an urgent fable about the empowerment of “finding oneself”.

This analysis mainly deals with interpretations (that part can be jumped directly to here), along with a running discussion of visual motifs. Starting out, however, it is useful to walk through some central scenes to suggest the reasons for the enthusiasm Thelma is causing. (The climax scenes are skipped, since they are richly explored in the interpretation part. The author has also produced a piece on references to Trier’s own films, here, although in Norwegian its extensive use of screenshots ought to give an impression. References to other films – there are many obvious forerunners and points of reference – are outside the scope of this analysis.)

This analysis is followed up with a second article further exploring motifs, as well as the film’s many elegant visual ideas, echoes and mirrorings. There is also a third piece with a close reading of Thelma’s epilepsy test, the film’s crowning achievement.

*

First of all, however, brief comments on the actors: Henrik Rafaelsen as Thelma’s father does not have the widest expressive range, but in Thelma this is turned into a virtue in a restrained, quietly frightening performance. He is friendly, commanding, but with a sleazy undercurrent and a slightly mocking gaze – most pronounced in the early restaurant scene. And his apparently unhinged act during the prologue, nearly killing his child, remains with us as an after-image, constantly projecting unease in the first half until we start to realise the underlying family tragedy. Ellen Dorrit Petersen as the mother has less space for impact, but her lightly parodic, exaggeratedly friendly tone early in the film, where she is cooing like a pigeon, is delightful. (These two will be referred to as Father and Mother in this piece.)

Eili Harboe possesses that rare chameleon-like ability to change her look and presence, responding distinctively to lighting, camera angle, hairstyle and make-up. Except for the flashbacks and a few situations towards the end, she is in every scene in Thelma.

Grethe Eltervåg as “Little Thelma” is convincingly confused by the unintended results of her powers, and displays one of the most fateful index fingers in Norwegian film history. Vibeke Lundquist as Thelma’s grandmother is unnervingly believable in her blank remoteness, but she still pulls back from Thelma’s hand. Even a witch with dementia seems to be able to feel the bad vibes from a colleague.

*

References to the original soundtrack abound in this analysis. This should surprise no one, because the score must be among the finest in Norwegian cinema. Ola Fløttum has composed most of the expressive themes, but the score is a latticework of contributions, also from Torgny Amdam & Mattis Tallerås, and Johannes Ringen, in addition to sound designer Gisle Tveito having made some connective material. Other important members of Trier’s regular team is co-scriptwriter Eskil Vogt, cinematographer Jakob Ihre and editor Olivier Bugge Coutté. The many special effects are excellent and seamlessly intregrated.

*

I: “Non-submersible units”

Stanley Kubrick claimed that all he needed to make a film was six to eight “non-submersible units”. Such a unit is a scene/sequence that is in itself so powerful and memorable that, in co-operation with the other units, will keep the whole ship afloat, possessing inherent qualities that can withstand any number of screenings. While analysing Thelma I have often thought about this expression.

The prologue. Fløttum’s main theme is immediately arresting: dark, majestic, sonorous, resigned against black credits. The opening shot, with its quietude, glaring light and minimalism of a man and a child on a polished ice surface, strikes us with great contrast. Thelma also provides an astonishing, grubbily poetic image from under the ice, an early hint that Thelma has the power to attract animals and a forewarning of her baby brother’s fate.

Then, as if signalling the film’s range, we are inside a forest with a limited view, and become shocked witnesses to the near-killing of a child. The important colour of red is introduced to the film, in various items in Thelma’s clothing.

The hair montages. An emotionally beautiful passage where Thelma is fingering Anja’s hair in bed, warmly accompanied by a Fløttum drone, continuing in a sequence where the new friends wander through the landscape and have a beaming rendezvous at the University. It ends with Thelma finding a single hair after Anja in bed.

The “Jesus Satan”/balcony scene. Anja follows up her dancing lesson by teaching Thelma to drink, swear and smoke. It is obvious that Kaya Wilkins is as delighted as we are about Harboe’s virtuosic comic turn when attempting to swear convincingly. Their natural interaction continues on the balcony, in the film’s most intimate scene, where muted colour patterns in the background, Anja’s hair in the wind, and yet another lovely Fløttum theme all play in harmony. The result is a small short film that perfectly expresses a human being’s relief over having found peace and belonging.

The ballet scene. The film now shifts into a higher gear with a rousing set piece during a ballet performance at the Oslo Opera House, where Thelma struggles with the fear of getting another attack. Not only is Philip Glass‘s 2nd symphony rhythmically interweaved into Thelma’s own harrowing emotional ballet, but the whole situation is edited to resemble an anxiety attack. The black-clad dancers have replaced the crows from the first attack at the University: they look at and step towards Thelma, waving their hands as if mocking her own hand that she is clenching to maintain control. The name of the ballet, “Sleight of Hand“, and its subject of a confrontation with dominant parental figures are in tune with the film.

The cloakroom kisses. Harboe is extraordinarily vulnerable as she with dark eyes, shiny with tears, throws herself at Anja, until her programming kicks in. Indoctrinated by religious taboos, she gets nauseous by the intimate interaction. After the hectic inferno inside the performance hall, the film suddenly stands naked in its total quiet and long takes.

Comfort by telephone. In the film’s longest take, a relentlessly static shot lasting 3 minutes and 14 seconds, with Harboe in profile, she again acts in virtuoso style, in a humiliating and infantilising scene. Tears and sobs come exactly where they are supposed to, with absolute emotional honesty, in a scene directed with a minimalist approach, with masterful use of telling pauses and play on the unspoken.

Just before, she prayed to God, but now she has a direct line to another loving but firm “God”: her father. It is heartbreaking how she is gravitating towards an unhealthy authority figure, to whom she cannot even be honest – things are after all endlessly much “worse” than she lets on – and eager for acceptance, she throws herself at the sword with great verve and enthusiasm. When she bursts out crying after hanging up, this perfectly sums up the emotional paradox: relief about Father’s “generosity” and desperation about having given up on herself. (Father’s “just make sure you don’t lose touch with who you are” hangs in the air, ringing with irony.)

The party/hallucination. Thelma gets cruel. She arrives at a party with a “trophy boyfriend”, sexily made-up, rather unlikable and narcissistic, and sends Anja packing in a rejection executed with deadly ordinariness, as if she is trying to infect Anja with her own denial.

The hallucination, where Thelma’s subconscious runs wild, mixing sexual desire with a religious vision of hell, is yet another bravura scene: after a chilling vertigo effect her studiously normal circle of friends are transformed into near-demonic beings with red hot lava pulsating under their skin. The idea of the snake seizing its opportunity to slither into Thelma’s mouth as she opens it in pleasure over Anja’s intimate caresses, ought to be extremely heavy-handed, but only comes across as transgressive and nauseatingly beautiful. (A poetic detail: the lone tear from Thelma’s eye as the snake takes her virginity.) The creeping, sensual, yet comforting string theme by Johannes Ringen is another entry in a film with extraordinarily accomplished sound and music.

The first flashback. In a sober but shocking scene, for the first time we get an inkling of Thelma’s abilities. Elegant longish takes give way to dramatic editing, with inventive use of low camera angles. Since this is a repressed memory the sequence starts with the camera gazing through a narrow door crack. The score’s main theme returns for the first time since the titles, with fateful power. Here we also learn that Thelma’s mother has not always been wheelchair-bound, but in a clever touch she is first shown in bed before we later with a mild shock spots her walking around.

The epilepsy examination. This is the film’s pièce de résistance – after this Joachim Trier and the entire team can die with a smile on their lips. Roughly in the middle of the film there are a series of 120 shots (about 12% of the total number) in a stretch of 8 minutes and 22 seconds – this includes a “prologue” (1m5s) where Thelma is first subjected to the flickering lights, and an “epilogue” (1m) at her hospital room that ends in milk, blood and broken glass. The main sequence is a controlled cacophony of images and sound, presented with contemplative intensity.

With its unpredictability and constant opening of new doors, it is also a microcosm of the entire film. Layer after layer are lifted methodically and lyrically away, until Thelma has given up everything, inside what turns out to be, shockingly, the peaceful eye of a raging epileptic attack. I do not think I have ever seen anything like this in cinema before, at least not with such a sustained, precise and careful inventiveness – the way our perception of time is stretched out, for example, is very sophisticated.

The unknown Anders Mossling is a revelation in the role as a neurologist; with his polished, melodic Swedish language and clinical calm, he is a down-to-earth contrast to the surrealistic proceedings. With a friendly but commanding presence, as if he were a stand-in for the director, he is pressing the right buttons to provoke Thelma’s nightmare, but her inner chaos can never be captured by any measuring device. (This analysis will return to this sequence below, and a close analysis of it can be found in the third article on Thelma, since virtually every shot is carrying distinctive ideas.)

The computer scene. In this scene, the images that Thelma is processing are not excavated from her subconscious, but float towards her in the form of a mesmerising computer-screen mini-essay about epilepsy and witchcraft. Fløttum is on hand again with a simple but hypnotic theme that strongly helps elevate a completely stationary scene to a highlight of the film.

The second flashback. Here Fløttum’s main theme returns in all its breadth, in a brilliant melodrama that ends with intense fetishisation – from three different angles – of Father’s powerless separation from the baby, encapsulated in the ice beneath him.

The window of the house. Again the main theme proves its versatility, entering into an audiovisual symbiosis with a tragic-poetic aspect. It accompanies a sequence where Father helps a drugged-out Thelma shower, takes her into town by car, and returns to the yard with Mother as an inscrutable spectator. She looks out of the window while an almost ironical, brighter iteration of the theme is playing, at the very point that Little Thelma once, to the same music, looked out of her own window, towards the lake and the dead baby.

Mother is thus connected not only to her own dead child and her daughter as a 6-year-old, but to the adult Thelma (half-erased already, memorably distorted by the window pane). Like the baby beneath the ice, Thelma is behind her own barrier. At the same time, the window and the death connotations lead our thoughts to Anja’s fate and the exploding window. The important colours of green and red are again naturally occurring in the landscape.

*

II: Interpretations

Thelma is a film with a lot between the lines and rich avenues of interpretations. In the following we shall primarily concentrate on the supernatural events.

Disappearance no. 1: The sofa

The 6-year-old Thelma only wishes to stop her little brother’s annoying cries. We see her concentrate. Is this just a child’s innocent game, or has she before experienced the ability to control the world? Whether this is Thelma’s debut or not, things go awfully wrong. She cannot control her power: not only the sound, but the entire baby disappears. Her mother speaks forcefully to Thelma, who in her confusion happens to press the right mental button, causing the child to resurface, but in another place, imprisoned below the sofa in the next room.

Apparently the baby has in the meantime been in the same sort of limbo in which Anja later will be parked. If it had been transferred to the sofa immediately, we would likely have heard its screams all the time. Just before it returns, we see a light under the sofa, a light not present before or after the baby has reappeared:

Disappearance no. 2: The ice

Fittingly for a film written by Trier and Vogt, with their often associative editing and longish digression-like montages, Thelma’s powers are associative. The baby is first imprisoned in a playpen, and returns from Thelma’s limbo in another “enclosure” (under the low sofa). It was in front of Thelma when she sat drawing, in a natural mental direction for her.

The same associative technique is in play when Thelma’s little brother later disappears from the bathtub as she lies dreaming. Here the baby is transported from one body of water to another, the lake. It dies, trapped under the ice. It is unclear whether the baby has been in limbo in the meantime, and only re-emerges when “the correct thought” has occurred to Thelma – but we see her sitting on the bed pondering, before she walks over to the window to look towards the frozen lake.

The disappearance no. 3: The window

Also during the epilepsy examination – which includes Anja’s disappearance – barriers are involved. In a strange way Anja seems to become trapped inside the window, with no one able to see her. (In a similar fashion we get the impression that the baby is inside the ice in the second disappearance.) Incidentally, Thelma’s range is increasing each time: the sofa in the next room, then the lake, finally Anja’s apartment a considerable distance from the hospital.

Anja is drawn towards the window, as if hypnotised by an invisible power. Then the glass explodes in a swarm of shards, which thereafter are pulled back towards the window, taking Anja with them, before the window reconstitutes itself. When Thelma later arrives to look for Anja, she spots a tuft of hair which is partly inside and outside the window. The disappearance itself is enveloped in a extensive film-formal apparatus reinforcing all this.

What is the associative aspect of the window business in this scene? This is much more subtle than before, but Thelma seems to draw a subconscious parallel between Anja’s window and the pane that separates Thelma’s examination room from the adjacent observatory in which the doctor and nurse sit. This parallel is supported by specific cinematic means:

When Anja returns from the laundry room, red objects are used like “warning triangles” for the coming disaster. One of Trier & Vogt’s favourite films – to such a degree that it has named their production company – is Don’t Look Now (Nicolas Roeg, 1973) where red is a very important colour, so such a technique ought to be familiar to them. (In that film too a dead child, which drowned, casts long shadows.)

“If you truly desire something, you can make it happen,” Father says. (Thelma means “will” in Greek.) Why would she now “deep within” want to erase Anja, whom she in fact loves? One reason is that Anja, as revenge for Thelma’s betrayal, was in on the plan to humiliate Thelma at the party. According to one of the associative images Thelma produces when the doctor encourages her to think about painful things, Thelma’s imagined drug intoxication made her masturbate in front of the other party guests. (At least, she is afraid that that was what she really did while hallucinating that she was making out with Anja). When the doctor then says “go deeper”, Thelma conjures up an alternative version of the image where we saw her vomiting: now she throws up the snake she imagined had entered her.

This suggests that beneath the pain, the shame over having been humiliated in connection with sex, there is something even worse inside Thelma: the concept of sin. Here it is important to remember that religion, according to her parents, is the thing that has restrained her supernatural powers – not least, the religious indoctrination has probably helped repress the terrible memory of her killing the baby. In Thelma’s world Anja is the very source of her lesbian desire, which now threatens the religious foundation that has kept so much awfulness in place.

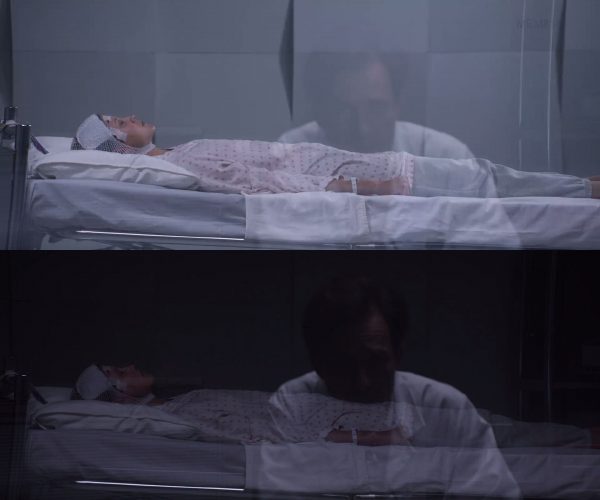

After the epileptic attack is over, Thelma hurries to her room. The small epilogue taking place here, with a broken glass of milk and blood floating on the floor, is not just an unorganic, forced horror movie episode, but plays meaningfully in relation with the disappearance. Due to an urge deep inside Thelma, she has broken the window in Anja’s apartment and erased her from existence. Now Thelma’s nosebleed drips into the glass of milk, the shock causing her to let go of it. Like her “deep inside” wish to remove Anja, the bleeding is something outside of her conscious control – and both of these situations end up breaking glass. Also, just before the milk incident, Thelma has tried to call Anja, without success. The breaking of the glass of milk can be read as a symbolic answer to her call.

Milk is a symbol of life, by the way, and Anja’s life is canceled “because of” the blood that now floats in the milk. Blood as a contaminating element of the milk with a fateful effect also points forward to the cup of tea, laced with tranquiliser, that Mother encourages Thelma to drink. We can also draw a line even further, to the cup Mother intentionally breaks on the floor later in the film.

The swimming pool

Before Thelma visits Anja’s empty apartment, she has almost died in the swimming pool, unable to find her way out of the water. This scene too may give the impression of a forced suspense element, but is on the contrary meaningful. This is a case of self-abuse or a suicide attempt. Thelma has just returned from Hellersmo Nursing Home, where she has learned that her grandmother blamed herself for Thelma’s grandfather’s mysterious disappearance, and also claimed that she had given herself cancer as “punishment” – something that is dismissed by the nurse as a delusion. Thelma nevertheless realises that Grandma possessed the same mysterious powers as herself.

The idea of punishing herself for her own bad deed is therefore planted in Thelma. Even though she has not yet checked out Anja’s apartment, after the epileptic “dream” during the examination she has a very strong impression of having hurt her friend. The guilty feeling only increases after Thelma can confirm the existence of her powers though Grandma’s story. During that visit the film music plays a theme resembling bells faintly pealing (by Fløttum), elegantly suggesting Grandma’s past and memories. On Thelma’s bus back to Oslo the theme returns, but now stronger and clearer, with a symphonic foundation. We sense that Grandma’s problems and feeling about her powers now are in the process of becoming Thelma’s own. Furthermore, the repressed memory of her killing the baby is probably starting to itch, in step with the intensity of Fløttum’s music.

At the same time it is still impossible to raise Anja on the phone, and Thelma waits in vain for her to turn up during the math lecture. (Here there is a little humour in the casting: she eagerly turns to the door as it is opened, but in addition to it being a boy, therefore emotionally of no interest for Thelma, the guy looks awfully geeky and unattractive.)

At the pool Thelma feels guilt on many levels: the conscious (Grandma’s sinister, related abilities), half-conscious (something is wrong with Anja), and the subconscious (the death of her little brother). When she gets an epileptic attack and sinks into the pool, it is once again her “deep within” that is in control.

With her ability to “make things happen” and reorganise the physical world, Thelma erects a barrier that will stop her from getting out of the water. It looks like the pool has been turned upside-down, since what she is hammering against has the same colour and lines as the bottom of the pool. I have little faith, however, that this is as simple as she has swum down instead of up after the attack has ceased. For how big is this pool, actually? Unless the images of Thelma sinking are purely symbolic, it is way too dark down there, and she sinks too far for this to be a normal pool.

In an elegant parallel, the barrier in the pool also mirrors the ice that trapped the baby – we are talking about self-punishment with bitter poetic irony. (In the film’s climax we will yet again experience this connection between the lake and pool. The latter also echoes the bathtub from which the baby disappeared.)

Thelma fights the barrier in vain. Finally her death wish is overridden by self-preservation, and without understanding what she does, she removes the barrier and manages to crawl up on the edge of the pool. Note, however, that she does not do any extended swimming before breaking the surface; she just spins around her own axis a few times, and suddenly she is up. And look at the last shot before that happens:

The scene’s ending, where she crawls up on the edge and lies there in a 27-second creepily meditative shot, is yet another beautiful idea in Thelma. She is filmed from a vantage point down on the pool surface, with a swaying camera slowly drifting away, as if it represents an evil force that reluctantly lets her go.

Homecoming

After the pool incident the colours in Thelma become drained, mirroring the heroine’s depression. With ghostly drones on the soundtrack – a small highlight in themselves – she is trudging along grey streets to Anja’s apartment, and on this occasion Trier hides almost completely the very red objects there and instead emphasises naked white walls. Soon Thelma goes home to her parents, and here Trier slows the pace several notches – a brave decision towards the end of a “suspense film” – except for the melodramatic second flashback, where also Little Thelma’s colourful clothes make a comeback.

The parents’ faces have been absent from the film for over an hour; they have only existed as voices in phone conversations seen from Thelma’s side. It is therefore fitting, and subtly unnerving, that the establishing shot of the first scene in their house shows these by now slightly unfamiliar entities from behind.

This part of the film contains some of the most determined use of hands as a motif:

Towards the end of the period in Thelma’s childhood home, two consecutive situations arise where the parents are towering meaningfully over the daughter. The first one is in the kitchen, an inscrutable scene where Mother intentionally breaks a cup. Is it meant as humiliation, a passive-aggressive reminder to Thelma, who has to pick up the pieces, that it is she who has caused Mother’s ruined life? Being paralysed, it is much for difficult for Mother to deal with the rubbish.

Mother’s gaze as Thelma looks up in an unguarded moment tells her that her parents are in the process of giving up on her. The same evening, the last time Thelma sees Father alive, she asks him in vain to set her free, and looks at him with burgeoning hate in her eyes. We have reached a point where the unconditional love between the family members is collapsing: the mother wishes (probably) her child to be dead; the child wishes her father to be dead.

One of the author’s few caveats about Thelma is a certain lack of clarity about what is really at stake after the parents give up on her, out of fear since even in a drugged state it turns out she is able to summon mental powers to blow out candles. Is Thelma to be hidden away in a nursing home? When Father is standing with the syringe, in the image below, is he going to kill her? Or is he just making it ready for later use? I have even entertained the thought of collective murder/suicide for the whole family (not an unknown phenomenon in reality), considering Mother’s remark about meeting the baby again in the hereafter.

If the intention is to kill, the shot seems strangely heavy-handed, with the rifle on the wall above him (even more so as the camera is pulling back, revealing ropes that resemble nooses). Here the storytelling falters a bit, and the film becomes, in a brief spell, too ambiguous. Father deposits the syringe in the closet after some hesitation, but what is behind it all is vaguely communicated: for the most plausible interpretation is that he has intended to kill, but cannot bring himself to do it – just like in the prologue, with the rifle, and it is now placed in the shot as an (insufficient) signal for us to understand his thought process.

Instead he decides to increase the medication – the score supports this, since the scene repeats the rasping, dragging theme that accompanied the drugged tea – and this is the reason that Thelma is so out of it in the following, unable to wash herself. Ironically, Father’s pangs of conscience become the direct cause of his own destruction.

Climax 1: The father and the boat

During the climax, with Father’s “self-combustion” in the boat, two strands inspire Thelma’s deadly dream. The first one is a childhood memory about Father holding her hand above a candle and waiting until she nearly got burned before he pulled it away, admonishing her: this is how it is in hell all the time. (One suspects that she really “met God”, as Father calls it, as a result of some determined scaremongering.)

That event seems deeply embedded in her, because when she speaks of Father to Anja, it is the first thing she brings up – and Thelma’s powers are after all governed by what she feels “deep inside”. Perhaps Daddy himself could burn? The fact that the fire specifically starts in Father’s hands points back to this, and of course also to the fact that Thelma’s own epilepsy attacks starts there. (Hands are, as we have seen, a central motif of the film. Candles are also interesting here.)

The other strand is the fate of Grandma’s husband: only an empty boat was found. It is perfectly possible that Thelma’s grandparents once lived in the same house as her parents, and that Grandpa disappeared on the same lake – even from the same boat – that will now swallow Father. Anyway, that story becomes raw material for Thelma’s subconscious, but simultaneously quite conscious death wish directed at Father, now that she has a strong impression that the parents have given her up, and the best she can hope for is sharing Grandma’s fate, drugged out of her mind in an institution.

Why does he actually go out on the lake? He smokes a cigarette, far away from people, very early in the morning. Is he smoking in secret? We have never seen him smoke before. Might his strict religion demand the renouncement of not just alcohol but also tobacco? In that case there is comical irony in the fact that he will go up in flames just like the cigarette – truly God’s punishment.

Or is it part of Thelma’s dream, that he is driven out to this strange place to smoke? In a glimpse before he is set on fire he sees his daughter clad in white standing at the shore. Is her dream so powerful that she can project herself out into the world, or is he seeing into the future? Is this supposed to be a sign that he too has a glimmer of the power, inherited from his mother? Is this the reason that the crows now start to circle him from above, not drawn to the house, like during Thelma’s first attack at the University? (It is not an attack now, however, but a dream.)

Father’s hands are trembling, in a parallel to Thelma’s own epilepsy, and smoke starts coming from them, before they burst into flame. He goes under, covered by fire. On the soundtrack we hear the same rasping, rapidly pulsing drone as when Thelma discovered Anja’s tuft of hair in the window, that too a result of her work. Now three generations have ended their days on this lake: Thelma’s baby brother, Father and probably Grandpa, all of them victims of the power. (Mother’s fate is also part of the pattern, since the suicide attempt happened from a bridge spanning a river.) Soon Thelma seems meant to go the same way, but instead she ends up reborn.

Climax 2: The vision in the swimming hall

Little Thelma went outside in her pyjamas to point out the baby’s whereabouts to Father. Echoing this, Thelma now leaves the house, again in her night clothes, wandering down towards the shore. The scene also resonates with her embarrassing exit from the Opera, not only in situation and the emotional turmoil, but also in the score, through an organ theme reminiscent of the opera exit.

After a gasping Thelma has realised that the boat is empty out there on the lake, she walks into the water and starts swimming. What goes on here, actually? Is she trying to save or at least find Father? For that to be the case, her initial movements are strangely slow. Is it a suicide attempt, like in the pool, where she was near death; is she now going to swim so far down that she will never find her way up again? Or is what awaits her on “the other side” something she has seen in her dream? Anyway: while she was sinking helplessly in the pool, she is now swimming very purposefully.

With the camera closing in on her in a beautiful, magically dreamy movement, she is forging ahead down into the dark, until lights start to flicker. This is a pattern seen many times in the film, signalling an upcoming attack. Is it a sign that the current journey is a hallucination? Thelma is ambiguous everywhere you look, without it being irritating, only inspiringly productive.

The flickering lights are transformed into two solid lines, which actually have to be the ceiling lights of the swimming hall. For in the next moment, Thelma breaks the surface of the pool. In this magical zone where two locations intertwine, “downwards” into the lake at some point has become “upwards” in the pool.

On her way we also see Thelma’s reflection – how can that be possible down here? This is reminiscent of how she “was swallowed up by herself” at the pool. Is it some kind of mirror world she is about to enter? (Our thoughts are led to the window of Anja’s apartment and the mirroring of her before she disappears – probably into the mirror image.) We have earlier entertained the thought of a limbo in connection with how the baby disappeared from the playpen. Did Thelma know what was waiting down here, and was that the reason she was swimming so purposefully? She does not seem at all surprised to see Anja.

What meets Thelma at the swimming hall may also be some kind of death hallucination – which fits with the light she has passed through. (Bright lights are a convention for describing near-death experiences in films.) In addition Mother not long ago said “we will all meet again” – followed by a cut to a photograph of her and the dead baby – underlining and lending extra resonance to the idea that Thelma’s encounter with Anja at the pool is the vision of dying person. The peaceful situation that meets Thelma is in fact reminiscent of an “afterlife”.

Thelma climbs out of the water and meets Anja, in a stylised, idealised edition, almost like a marionette. They kiss wholeheartedly, in a serene and “pure” version of the ravenous kissing in the opera cloakroom, and the sensual, “hedonist” interaction of the party hallucination. It seems that the Anja she meets now is a pure symbol of Thelma’s yearning.

There is also a progression. In the first pool scene she looked up at Anja from the water, with her on a pedestal. In the second scene, where she almost drowned, she managed to get up into a prone position. Now she has stepped up fully, and they exist side by side, at the place where they talked to each other for the first time.

The moment is also connected to the first place they saw each other, at the reading hall. Through the window we see a collection of crows, like the flock around the University just before Thelma’s first attack. Anja was clad in black both at the pool and the reading hall – she has been connected to black or dark clothes throughout – relating her to the crows, these “witch birds” that often symbolise corruption. Again one bird is set apart – the crow that probably died as it struck the window the previous time, is again on its way to destruction. The window is therefore connected to death and Anja’s disappearance (and all the other barriers in the film).

The whole scene, from the point that Thelma breaks the surface, is captured in one long take (all of 44 seconds). It ends with the camera pulling back again, in a reverse echo of how the camera was closing on the window during the reading hall attack.

This time, however, just as the bird is about to crash into the window, Thelma wakes up in the lake near the shore. It is tempting to think that there is symbolic connection between her and the crow: Thelma too would have died if it had struck the window, but she managed to snap out of it and back to life. She also seems to have saved the bird from dying this second time. The symbolic connection is not exactly diminished – to put it mildly, because this is a very brave scene! – when she proceeds to cough/throw up a small black bird, a miniature version of the crow, which falls to the ground close to Thelma.

This can be related to a number of other situations. Thelma is nauseated by the violent kissing in the cloakroom. She vomits after the hallucination where she has kissed Anja. The symbolic snake that enters through her mouth as Anja is caressing her, is thrown up when she “replays” the moment during the epilepsy test. In addition the red hot “lava” pulsating beneath the skin of the characters is portrayed as if entering Thelma’s body:

Could it be that she is now not only getting rid of the bird, but also what has before made her nauseous? For the bird is returned to life, and eventually flies away. Considering the symbolic link between Anja too and the crow, it is furthermore a reasonable interpretation that it is the kiss with Anja that has “given” Thelma the bird – like the snake and the lava previously entered her. Now, however, the kiss has a positive, life-affirming effect, which not only enables Thelma to gain control of her supernatural powers, but also to accept her sexual orientation. And now that Thelma has brought the crow from the underworld back to life, she will also be able to wake up Anja.

Water is a common symbol of the subconscious, for example in Jung’s thinking about the collective unconscious, and in Hans Biedermann’s “Symbol Lexicon” water is called the basic symbol of all unconscious energy. (Thanks to Oskar Abel Valand Halvorsen for having pointed out these things.) This may illuminate Thelma’s journey into the depths of the lake, as well as its purposeful nature. Symbolically, she dives deeply into her own subconscious, which is both the source of her powers and holds the key to retrieving Anja back to reality. The swimming hall then becomes a natural extension of the lake – in line with the associative pairings of playpen/sofa, bathtub/lake and the two windows – and her previous near-drowning there and possible death wish become tied even stronger to the subconscious. Thelma’s new access to this part of her mind may also help her to soon gain full control over her powers. Furthermore, water often symbolises transformative processes, which fits nicely with Thelma’s situation in what now comes.

Climax 3: The revelation

It cannot be denied that Thelma contains some Christian symbolism. Britt Sørensen has in her review for the newspaper Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian, behind a paywall) mentioned Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his own child for God, The Holy Ghost revealing itself as tongues of flames at Pentecost, and the snake in Paradise. (Here is another good point, about the prologue: “a delicate, vulnerable deer that could well be read as a symbol-heavy metaphor of the young woman Thelma has become when we meet her again as a fresh student at University.”) In addition comes, of course, Thelma’s healing of Mother towards the end of the film.

The religious symbolism springs primarily from the presence of Thelma’s fundamentalist Christian parents, against whom she finally rebels. After the vision in the swimming hall, Thelma lies on the moss by the lake and is obviously experiencing some kind of revelation. But is it of a divine nature? One could of course say that it is the Old Testament, strict, avenging God she is rejecting – the divinity that would not hesitate to burn people like Father in the boat – and instead embracing a loving, tolerant God. In this type of story, with rebellion against religion, it is not unusual with a subtle manifestation that there is a real God, whose teachings have been distorted by fundamentalists. Is this what happens here? The film is likely intentionally ambiguous: we may interpret a divine vantage point and power into the final scenes and thus a proof of God’s existence, but it is as likely that Thelma realises that the Lord is just an illusion, and that this insight is cathartic too – just in another way.

It is true that Anja disappears when Thelma asks this of God (during the epilepsy examination), and as we shall see, she returns in a situation that can be related to something divine. The fact that Thelma is subjected to a lot of tests in the course of the story also resonates with Mother’s statement “we’re being tested”: Thelma’s presence in their lives is a test from God and their religious worldview commands them to kill the child, regardless of how painful it is to them personally. (Thelma is also “tested” by the neurologist who encourages her to delve into painful things.)

When Thelma storms out of the Opera and during her intense prayers afterwards about “take them away” – could God please be so kind as to burn out of her the thoughts of desire for Anja – this is accompanied by an organ theme. This is repeated during the “revelation”, hinting at a relationship between the scenes. But there are no signs from above, only Thelma lying on the ground, surrounded by nature.

The prayer is finally heard, when it returns during the epilepsy test, but no God is involved – unless Thelma is in the end a tool for God. When the organ theme returns as she lies on the moss, her desperation has gone. If it is at all a prayer involved now, it is a silent one, a life-affirming one, reflected in the peaceful images of a larva and a beetle that will soon come. Animals have previously appeared as threats, but now embody positive symbols, parts of a greater cycle of life.

As Thelma is staring at the bird she has thrown up – the blackness she has previously rejected and has nauseated her – it is her own life and self-worth she is looking at: she has now accepted herself, and as a result of this everything wakes up – both the bird and Anja. Thelma accepts life and death, the balance of the universe, the reality that just exists independent of her, for its own sake.

Her sexual orientation is in a way inseparably bound to the supernatural powers, and both are as natural as the beetle and the larva. God is irrelevant in this scheme; it is through self-acceptance that she now achieves full control over her abilities, and can bring Anja back just by thinking about it.

Unlike Anders in Oslo, August 31st (Trier, 2011) she has rejected suicide, and this creates resonance, due to the many connections between the films: the drowning attempt in the earlier film is recreated in Thelma, and both films feature extremely unhappy protagonists who have caused great pains for their closest ones. The technique in Oslo of repeating the same images but with the absence of the person who previously inhabited them is also used towards the end of the epilepsy test. A swimming pool becomes an important location in Oslo too.

The two shots above are of interest as a pair: they complete each other, like the two lovers kissing in the vision. Thelma looks up at the heavens after having got rid of the black bird, and the entire sequence ends with the heavens “looking” down at her. Her point-of-view shot is thus balanced by what is often called a divine point-of-view, suggesting a being looking down at the ground from a great height. Her gaze up at the heavens can be interpreted as an inquiry to God, but in that case the overcast sky is the only response – there is no sign of a revelation. And if “God” looks down at her, there are still no specific signs of a revelation, everything is still soberly presented.

This can be read against two other constellations of images from above:

Thelma is lost and anxious after the creepy dream about the snake, and there is a direct cut to an “inhuman” shot where people are merely ants in a stony desert. There are far more positive vibrations in the next overhead shot of Thelma in bed, now with Anja in place:

And the stone desert is now fertile. The last pair of shots both contain revelations, first of personal love and then a larger love, comprising the whole world. In both situations (as well as the shot where she looks up at the sky) the camera is rising slightly, in the exterior shot something that could be interpreted as a yearning for higher powers. But the overhead shot could equally well just emphasise that Thelma is part of a very concrete physical world and the height is to show that Thelma is a minute part of “the larger picture”. Nature is no longer frightening, with its scary crows and dangerous snakes, but an entirely prosaic world that is still full of small miracles. “How did life come to be where there was no life,” Father asks, and as an answer these images come:

This is part of a cycle (beetles come from larvae) that is endlessly repeated, without any divine intervention or control. In Buddhist philosophy it is said that one reason for suffering is selfishness and a false idea about a barrier between oneself and the exterior world.

Or perhaps we should go to another area within Eastern philosophy – something Thelma definitely allows for…

…a pattern we also see here, as they wake up from the key scene we discussed earlier:

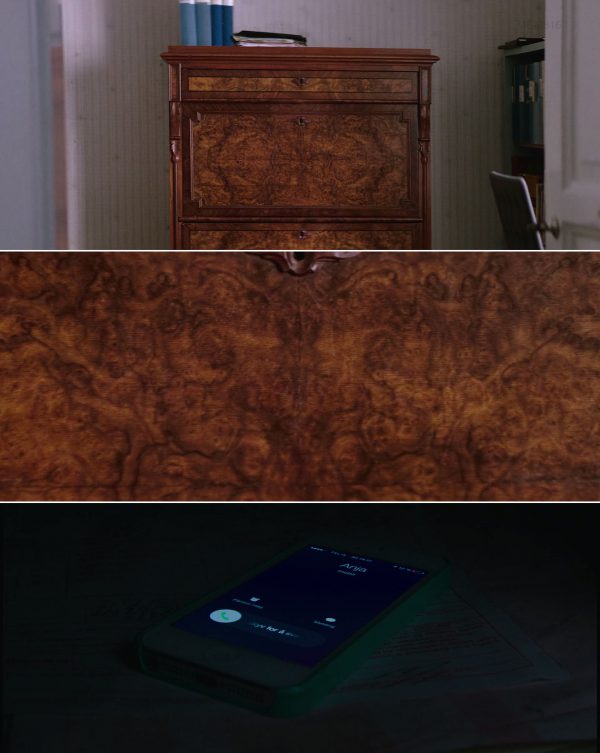

The larva and the beetle are followed by a dramatic camera movement towards a chest of drawers and through it, as if underlining the transgressive and liberating nature of Anja’s return:

The barrier motif (the sofa, ice, windows) is maintained, since the phone with Anja’s call is imprisoned inside the drawer. The darkness in there is alleviated by the call, one of the many lights in the film. The phone is green, like the moss Thelma is lying upon. Also note the Rorschach-like, virtually symmetrical pattern on the chest’s surface.

Even though a non-divine interpretation of Thelma’s “revelation” is plausible, there are good arguments in the opposite direction. After Thelma has woken up in the water, she crawls to the shore in this shot:

So, another divine point-of-view, even followed by a gaze of wonderment at this miracle of a bird – and thereafter at the potential being who performed it.”Not a sparrow falls to the ground without God willing it,” is a religious saying, and it is in fact possible that this is one, a lark bunting. The “sacred” organ theme starts as she turns and directs her gaze towards the heavens.

Thelma is a fictional story, and since we have already accepted the idea of supernatural powers, one can always be generous and include divine beings too. In this interpretation an observing God says: “I saved you from death, and your powers that formerly caused such damage I shall give you full control over, so that you can perform my will on Earth.” Here she is saved like a miracle just before she dies from drowning, and the bird is a sign from God. It also comes around and flies away while God looks down at Thelma. Her gaze towards the sky is in recognition of this divine intervention. Incidentally, rebirth was already hinted at in the religious choir’s song about Jesus: “The power that conquered death lives on in those who are his. The grave is empty, Jesus lives now.”

Here the larva, beetle and the camera penetrating the chest of drawers are expressions of God’s miracles. The phone ringing in the middle of all this becomes an ironic comment on Kristoffer’s “it’s not God, I know that for sure”, when he tries to answers the question about how his phone works, during the discussion in the bar. (Kristoffer’s name originally meant “Christ-bearer“.)

Climax 4: The healing of Mother

Before she leaves her childhood home, Thelma heals Mother’s paralysis with an inscrutable, almost arrogant smile, and an otherwise impervious expression and body language. It also seems like Mother regains, if not motherly love, at least some ability to love, since her features are softening.

Is Thelma a Jesus, or perhaps a witch, as hinted at through the Youtube essays on epilepsy (or a “Jesus Satan”)? It could as well be an ironic, almost mocking turn: You who are a Christian, Mother, look here, now I’m healing you like Jesus. (And now I’m leaving you.)

Now it is Thelma who is towering over Mother again. A “divine” light enters from the window (the overcast sky has given way to sunny weather, but the light is still abnormally strong), but neither this is unambiguous proof of God’s existence. It is rather the culmination of light as a motif in the film, which so far has flickered – in connection with the supernatural events or the epileptic attacks, but also the lights in the reading hall that are rapidly turned off and on before closing time, the strobe lights on the dance floor with Anja afterwards, the pulsing light during the MRI scan, and the extreme flickering of the epilepsy test. (It is the epilepsy lighting equipment that makes the film’s title card flicker, and this is the rationale for the subliminal shot popping up just afterwards, an effect the viewer can only vaguely sense.) The light from the window also forms a meaningful contrast to Thelma mentally blowing out the candle on Mother’s bedside table.

The sustained light penetrating the house can also mean that Thelma too is now healed and completed. A beautiful side effect: for the first time in the film we here see clearly that she has green eyes, one of the film’s two important colours. Admittedly, it is visible during the epilepsy test, but there is so much going on at once, in such a flickering light, that it is difficult to perceive. (Thelma’s healing touch is of course part of the extensive hand motif, already discussed here.)

The healing takes place in the same room where the baby disappeared from the playpen – respectively, the first positive and negative effects of Thelma’s abilities we see in the film – and Mother’s paralysis after the baby’s later death is indirectly Thelma’s fault. And considering the situation with the broken cup (see here and here), where one of the points was that Mother had difficulties picking it up, it is very nice that it is precisely in the kitchen that Mother afterwards discovers she can walk.

In summary: the climax has united the fate of several generations, the lake and the pool, nature and civilisation, the rural and the urban, death and resurrection. Thelma’s white clothes recall the visual purity of the film’s striking opening shot on the frozen lake. In addition to the rebirth of Thelma, Anja and the bird, Mother’s physical condition and, not least, some part of her humanity is reawakened. Thelma herself is both spiritually and psychologically renewed, and is compared via two shots that are probably meant to resonate with each other:

We have seen the last jacket only once before in the film, when she visits Grandma, so she is also a little reborn in her clothes. The colour of the inner lining is the same as the stripe on the beetle, which represented the cycle of life, and the jacket is swung conspicuously so that the blue is visible several times. The cross has gone – good news for everyone who would like to keep God out of it. (But this may of course just mean the final break with her parents’ version of godliness.) Thelma’s march away from the house is marked by a cheerful, triumphant synth jingle.

The epilogue

Thelma seems to have a completely happy landing in the short epilogue, where the heroine meets Anja at the University. Still it cannot be denied that the scene contains an undercurrent of ambiguity. The devices are subtle and demands thorough inspection.

We perceived an undertone already during Thelma’s last encounter with Mother: her unfeeling, almost triumphant behaviour, and strikingly little remorse or sorrow over Father’s demise. It is also curious, and perhaps a weakness in the film, that her attitude has changed so suddenly, compared to the humble mood of the revelation just before. But remember her remark to Father about the inexplicable tendency to feel she is better than everyone else – is this in full bloom now? With great power comes great responsibility, the saying goes, and how will a young person cope with the godlike powers she demonstrated with Mother, and the ability to change the world at will?

While waiting for Anja, Thelma has a slightly self-important and arrogant, almost cunning expression, as she stands looking towards a tree, while the camera is slowly gliding towards it – as if Thelma is pulling it towards her. Is nature, including the far-away crows she hears, now under her control? Is it this communication with nature that provides the power for what now happens: an episode that might indicate that she controls Anja? Was the flow of light something similar, giving her the power to heal Mother?

Perhaps Father had a point with his skepticism about the love between Thelma and Anja: “How could she have any choice, with what you have in you?” Such an idea might be provocative, especially since sexual predators in connection with homosexuality is a bad cliché of the past. Positive role models are great, but Trier probably has a wider agenda than “just” lesbian self-realisation and acceptance.

A contributing factor to including the gay aspect in Thelma might be that this will mean a greater obstacle for a fundamentalist Christian girl to overcome. Furthermore, artists are usually not interested in delivering endings where everything is wrapped up neatly. Finally, the underlying (irrational) fear in every relationship – is it really mutual, might it just be an illusion or misunderstanding – is a subject Trier has been addressing in previous films.

We should not forget how Thelma pulled Anja to her apartment building – a key event in the development of their close friendship. In the dance scene earlier that evening, Anja has suddenly gone – together with the strobe light that foreshadows the flickering during the epilepsy test, this is of course a forewarning of her real disappearance – and since we never see Thelma say goodbye it is reasonable to assume that the others have gone off on their own. Even though Anja obviously likes Thelma, they seem in no way inseparable at that point, with reference to Father’s question:

This is easy to misunderstand, since we do not see the run-up to the dancing, but taken in context with the entire film, it is not likely that Anja was making a pass at Thelma. She is only teaching the religious backwoods girl to dance, like she later teaches her to drink, swear and smoke. When Anja starts touching her intimately during the ballet, this only happens after Thelma has learned that she has broken up with her boyfriend. So Thelma’s “deep within” knows that the coast is clear.

It is also odd that Anja would make advances with her mother at her side, especially since the ex-boyfriend was supposed to be a big favourite. Anja’s expression in these moments also seems strangely unanimated, as if she is not entirely in control of herself. It is conceivable that she takes Thelma’s hand in order to “confirm” the new friendship, and then Thelma’s powers are exaggerating the gesture (caressing the thigh and the movement towards the loins). In any case the scene is ambiguously shot and edited.

Nothing precludes that Anja might have developed romantic feelings for Thelma. At the party her disappointment over having been ignored and rejected seems genuine, and during the evening at Anja’s it is obvious that their rapport is excellent. The kissing at the Opera also seems mutual. Perhaps Anja just needed a shove and Thelma has awakened something in her?

The Anja we meet in the epilogue, is she the same, or is she refashioned, perhaps with some small thelmatic modifications? Is she not showing some of the same doll-like properties from the vision at the swimming pool, with a conspicuously unanimated face?

As we soon shall see, there is a hint that Thelma has some sort of control over Anja. After the kiss there is a cut to another position where they walk out towards the square, and also in the film’s last shot, some kind of enchantment seems to be broken; everything seems normal again, easy and natural. But the sudden idyll might also signal that the outwardly ordinary couple actually are something else.

The epilogue contains many estrangement effects. In the opening shot, filmed from the side, the tree in the background is quite a distance from Thelma; then in the next, frontal image it seems to be right behind her. The shot is probably captured with a lens that compresses space. (The tree is not dissimilar to the “one-dimensional” tree from the dream in Louder Than Bombs – see the shot above, to the right – which almost looks like it is painted on the wall or a cardboard model.) It would be odd to undermine a scene’s established geography unless the goal is to create a subtle feeling of unreality?

After she has looked at the tree, there is a cut back to Thelma’s face. The only passer-by is clad in black – Anja’s colour. Since no one accidentally comes sauntering by on a film set, this is potential foreshadowing.

We remember the episode in bed where Thelma lies as if mesmerised, studying Anja’s neck, hair and ear. Here towards the end there is an echo: Thelma is shown from a similar angle, possibly a further hint that something with Anja is afoot. At the same time the background is acting strangely: the image is floating and unreal. It is probably a combination of the handheld camera moving to the right and at the same time panning (as well as Harboe possibly moving her head).

Then Thelma imagines that Anja is kissing her on the neck, on top of a tuft of hair. Both of these things point back to the earlier bed scene, and Thelma’s general fascination with Anja’s hair.

When Anja now approaches from behind, in reality (below), it seems that Thelma knows (note the little sideward glance), but it could also be that she recognises her footsteps, because their relationship is so harmonious. (The natural sound disappeared when we saw Thelma from behind, but has now returned and the steps are audible.) Her face softens:

Can Thelma look into the future, like Father possibly did when he glimpsed Thelma on the shore, or does she simply will Anja to come, like when she drew her to the apartment building? Or can she, magically, hear Anja from afar? Is that why her ear was relatively centred in the frame and we heard an artificial hiss on the soundtrack? Or are the images to be interpreted as the relationship being so solid and safe, and so perfectly harmonious, that she just knows that Anja is coming?

In that case, the nature of the relationship would be a powerful retort to Father’s assertion of pure manipulation. A beautiful interpretive possibility is that it is not an oppressive form of religion but a deep love that is required to keep Thelma’s forces in check: therefore her slightly sinister expression immedately softens when she has imagined Anja and the kiss on the neck – like Mother’s face after the healing.

Or perhaps the situation is wholly innocent? They have an appointment and Thelma thinks: “How wonderful it would have been if she kissed me on the neck, where I looked at her that night, and now I recognise her footsteps, she’s coming, and indeed she’s kissing me.”

Interestingly, their colours from the swimming pool are reversed. Now Thelma is in dark clothes; Anja is all-white, and in a dress, both things a first for the film. Thelma even points out the change, that Anja looks like a “babe”. She herself wears Anja’s jacket, possibly the one she used when Thelma saw her for the first time, at the reading hall. It is unclear whether this development and fusion of the two is a positive or negative sign (the latter of a possibly unhealthy influence from Thelma’s side).

The initial shot of Thelma’s expedition into the elevated society at the Opera House forms a parallel to the University square shot: at first she fits in, here among a conspicuous amount of other dark-clad people, only to be spat out again, now into a heartbreakingly empty space. (Inside the pattern is repeated: a busy vestibule before the performance, which is then empty during the kissing.) In the same fashion she happily arrives at the party, but leaves it in humiliation. And earlier, at the bar and while dancing, she delights in the company of others, but ends up lonely in the park with Father on the phone.

Joachim Trier and his team have an outstanding ability to load gestures or actions so that they transcend their everyday meaning. Breathing thus becomes one of the many important Thelma motifs. The heroine wakes from her dreams with deep breaths and gasps. Her breathing is foregrounded on the soundtrack as she watches her own hand before pulling Anja to her building. She is breathing heavily, in strong premonition, as soon as she looks at the fateful window in Anja’s apartment, as she spots Father’s boat on the lake, and during Anja’s advances at the ballet. The neurologist constantly commands her to breath deeper, and via an orgasmic state where she is breathing in ultra-slow-motion in perfect alignment with the flickering light, the epilepsy test ends in convulsive deep breaths, in metaphoric exertion after having broken Anja’s window. It is also mental breathing that blows out the candles at her parents’ house.

But the entire film is breathing. The parallel expulsion scenes at the Opera, at the party and after the dancing form a rhythmic breathing in the film. The camera is breathing too: during Thelma’s first attack it closes in on the window as the crows are hurtling towards the reading hall, and it pulls back in the corresponding scene during the vision. Furthermore, the camera pulls away from her building and into the trees as a ghostly Thelma stands in the window looking out, and closes in on another building as the dream starts in the next shot. Nature itself is breathing when the wind starts blowing before Thelma’s second attack, outside her building.

But it is in the University square shots the film is breathing the most. It takes a deep breath as the camera is lowered towards the ground at the start, holds it together with Thelma through the entire film, and breathes out during the opposite movement in the final shot.

It is tempting to call Thelma a masterpiece. In this author’s eyes it is the most complex Norwegian film since Remonstrance from 1972 – that too a lyrical work embracing a large number of impulses, genres and moods. Joachim Trier thus continues a proud family tradition from his grandfather Erik Løchen.

I am grateful to Gisle Tveito who has patiently answered my many questions about an unusually intricate soundtrack.

*