Unbreakable, Part III: Visual style

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the third article about Unbreakable. The first one is here, the second here. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

Unbreakable is M. Night Shyamalan‘s formally most daring and distinct film. It is inventive, hypnotic and reverberates with formal echoes. Virtually every shot could be worthy of discussion. Its running discussion about film as an art form is a constant source of fascination, even in the few cases where his choices may come across as slightly mannered.

Leaning heavily on frame grabs, this article will map out M. Night Shyamalan‘s visual style, which is founded on a system of recurring formal devices. The two first Unbreakable articles have charted its great variety of recurring motifs and character connections. Shyamalan’s visuality leans on a similar interconnectedness. When one comes to know it well, watching Unbreakable feels like a ritual. There is something ceremonial about how all the types of recurring elements, like paraphernalia for use in the ritual, are applied and reapplied throughout the film, in new variations, sometimes operating together, in combinations that not seldom create new meanings. Adding to the sense of ritual is the obsessive use of certain motifs and techniques, for example the jerky motion that always starts and ends David’s visions.

Several of the film’s formal devices are common tools in the directorial box, but M. Night Shyamalan employs them with rare authority and confidence. I have divided the material into the following chapters (but due to the interconnectedness of his style, many shots under discussion will overlap with other chapters): meaningful camera movement, camera gymnastics, lateral camera movements, block and reveal, tight framings, overhead shots, upside down shots, foregrounding and staging in depth, long takes and cutting in camera and immersion. I will end the article with a tiny idea that must be one of the most absurd foreshadowings I have ever encountered in cinema.

In order to discuss the film properly, I will eventually have to reveal the whole plot, including the major plot twist at the end.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of Unbreakable, here is a brief outline of the plot.

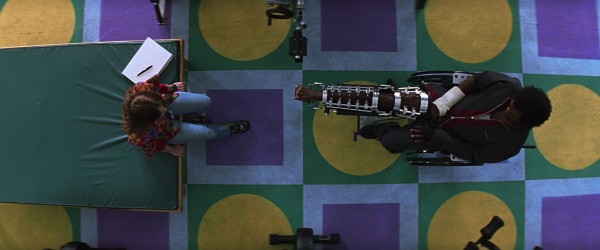

The weightlifting scene

Before the individual devices, just a little about one of the best and most amusing scenes of the film. The most of Unbreakable are long-take-based, but the weightlifting scene is edited more traditionally. This is precision-work, however, and the scene has a rhythm and fluidity that give it great watch-many-times durability. In this, it is reminiscent of the Mind-reading game in The Sixth Sense, and also in its use of variation within a limited framework. (Joseph’s ever-shifting positions in the room may even be taken as a playful meta-comment on this strategy.)

The pace is leisurely. It is as if the film takes a break for five minutes or so, just to do some weightlifting. Like the park scene that directly preceded it, it has a calm and mundane air that seems a deliberate contrast to the drama of the stadium sequence just before, with its chase scene and Elijah’s fall on the subway stairs. The early stage of the scene is shot with a static camera and conventionally edited, but as soon as Joseph says, “I lied” – he added to the weights instead of reducing them, because he wants to press his father to find out if he has superpowers – the film springs to life.

The earthiness of the diegetic Allman Brothers Band‘s “Midnight Rider” is suddenly dropped in favour of lithe and serene variations on the already-established themes of the film music. The camera wakes up as well, begins immediately tracking in, and the rest of the scene is a cinematography ballet, with breathtaking inventiveness and grace. But there is also playfulness, because the camera sometimes refuses to do what you expect. A range of the signature shots and devices described later in this article appear, turning the restricted space of the basement into a formal microcosm of the film and a sub-ritual within the larger ritual that is Unbreakable. At the same time, the movements are functional, intensifying situations and commenting on the characters and their relationship. It is highly recommended to watch this scene repeatedly to work out its intricate gamesmanship. The scene’s impish humour must not be forgotten either. And Bruce Willis really looks like he is doing a lot of the lifting unassisted:

Meaningful camera movement

In Unbreakable there is hardly a camera movement that does not carry meaning, turning this into a governing principle of the film. Meaning is often local to the shot, but as our first example will demonstrate, movements can create a persistent pattern across the film. On three occasions David rejects Elijah’s suggestion that he is a superhero. The rejections are accompanied by some very unusual camera movements, of great variety, but all suggest increased distance and emptiness. (Incidentally, is there something biblical about David’s three rejections? In the first article, I described their relationship as a bargain with the devil, and the second rejection takes place high above ground, which would fit both the second and third temptations of Christ. David’s many near-fatal accidents in the film, and especially his almost-drowning in the swimming pool, could be seen as deaths and resurrections.)

The first rejection comes at the end of a 58-second shot where a fixed camera has been gazing at the two, in a heavily stylised composition as if to encourage a feeling of weirdness. When David and Joseph leave, the camera tilts down to record this, before it briefly lingers on the empty floor:

The second rejection takes place at the top of the stadium. During a 132-second shot (the fourth longest of the film), they enjoy a quite friendly conversation. But at the very moment that Elijah begins pressing David about possible powers, immediately making David awkward, the camera starts pulling away slowly, until it stops, stranding them in a unusual and constricted composition:

The third rejection occurs directly after the kitchen scene where the obsessed Joseph has threatened to shoot his father. Very strangely, the camera seems almost disinterested in David and more concerned with the pieces of comic book art that book-end the shot, as the camera, right from start, glides laterally towards the right. The shot ends when David is about to completely disappear:

It is logical that the shot ends with the two framed comic book art pieces, since the rejection has left Elijah with only his comics obsession – and this logic continues since in the next scene Elijah is in a comics shop.

This last rejection is reminiscent of the famous telephone call scene in Scorseses Taxi Driver (1976). During Travis’s humiliating conversation with Betsy, who rejects him, the so-far fixed camera suddenly dollies inexorably away from him in a lateral movement, to end up staring down an empty corridor. It should be said, though, that Scorsese’s implementation feels more organic, a truer representation of Travis’ inner life. It is more striking, perhaps also because there are few others overt formal devices in his film, so his movement stands out while Shyamalan’s “rejection movements” are part of a larger system. On the other hand, they are meant to have a much more subtle effect and not as a direct metaphor of any character’s feelings.

When David finally accepts Elijah’s idea, this too is marked by an attention-calling movement. Elijah says, “It’s all right to be afraid, David, because this part won’t be like a comic book.” Before this the camera has rapidly pulled away from him, revealing an ominously dark corridor lined with comic books. This is another manifestation of Elijah’s immersion in comic books (we have not seen that corridor before). It also contrasts the world of fiction with David’s soon-to-come search for real-life criminals at the train station. The sudden distance to Elijah underlines that his mentorship can only go this far, and that David has to fend for himself in that real world:

A similar but more dramatic movement marks the enormity of the danger when Elijah is forced to negotiate the subway station steps when chasing the gunman:

Below the camera pulls back to reveal another staircase, here a symbol of David and Audrey’s separation (see also the staircase motif in the second article):

Here the camera pulls away from David to reveal the drug dealer. Here movement is mainly for storytelling purposes, but the peculiar manner of revealing him also underlines the creepiness of the dealer:

Below is one of the most beautiful scenes in Unbreakable, both visually and emotionally: a sad and tender reconciliation attempt, with the surroundings and backdrop lending artificiality, distinction, mystery and elegance. The camera movement helps invoke these feelings. At first David and Audrey tease each other, but as soon as she begins to get serious, this immediately sets off a movement, the camera slowly closing in on them, peeling off elements until only the essential is left. Not just a dialogue scene but a meditation on a dialogue scene (it is further discussed here):

The camera movement is thus triggered by a subtle change in the scene’s tone, which is the case in many other movement scenes. During the second rejection, we already saw David awkwardness setting off the movement. Such triggering also happens in some less elaborate scenes, where slow forward movement produces an intensifying effect common in cinema, but handled in outstandingly authoritative manner by Shyamalan: when the school nurse starts talking about David’s childhood; when David starts getting to the point in the scene where he asks Audrey if he has ever been sick; when Elijah starts talking about comic books in his first meeting with David.

We shall now have a closer look at one of the most elaborate, elegant and transcendent camera movements in Unbreakable. Supported by a variety of means, it visualises both Elijah’s thinking process and, metaphorically, how his tremendous willpower can overcome time and space:

The camera movement above is actually even more transcendent, for David’s weightlifting scene just before ended with a forward movement, whose momentum can be said to be transferred to the Elijah scene. We shall later see another example of such a transfer. (For additional information about this scene, see the second article’s discussion of its connection to the colour motif and the numbers motif.)

But camera movements in Unbreakable are not restricted to overt effects like many of the above examples. It is also full of very small, but still highly deliberate adjustments. Below Elijah has fallen on the subway stairs, quite close to the camera, but still it moves closer, and with such an implacable and authoritative air that it cannot just be an improvisation because Elijah ended up a bit too far away:

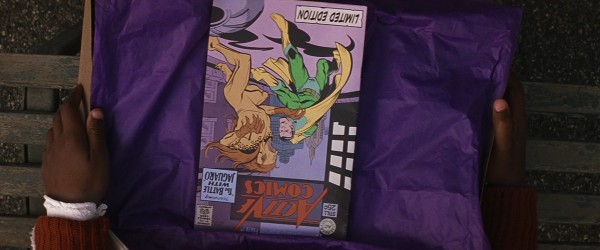

Here is another situation, where the 13-year-old Elijah is approaching the bench with the present. When he is close to the bench, the camera too gets closer, as if to accentuate the importance of the package and heighten the tension. The movement is so discrete, however, and our attention is drawn to Elijah’s own movement, so it mainly has a subliminal effect:

We see such small adjustments in many other scenes, for example when the camera almost imperceptibly closes in on David by the train window after the woman he tried to seduce has rejected him. Discretely closing in on characters is one of the most common ways a director can heighten tension or raising the emotional stakes in quiet scenes – Spielberg is very adept at this – but it is so pervasive in Shyamalan that he must be regarded as a master practitioner.

In many of the examples in this chapter, one gets the feeling that Shyamalan’s camera is able to react emotionally on its own, deciding to start moving. An often-used strategy seems to be shots with an immobile camera for a long while, but with movement “flourishes” either at the start or end. (At other times, scenes will mostly consist of one long take, but here the “flourishes” are some shorter shots at the start or end: for example the shot/reverse shots between David and the little girl that book-end the film’s longest take, the 229-second seduction scene on the train, or the two shots that envelope the 129-second shot of the kitchen scene with Joseph and the gun.) Typical is the scene where David comes to ask Audrey whether she can remember him ever being sick, which starts out as an immobile two-shot, but towards the end the camera sneaks in on a close shot of David and then one of Audrey – or many examples already covered, for example the first rejection scene.

The below scene is one of the most audacious examples. It is a 126-second shot that mostly treads water while we see the second survivor of the train accident in the foreground. One of its main points seems to be to lull the viewer into some kind of false security and then to rub him/her in the face with a severe hemorrhaging right in front of us:

Camera gymnastics

Most of the camera movements in the film are geometrical and tightly controlled, but in a few scenes they are less geometrical but no less less deliberate. The following 111-second shot is interesting in another way too, because it seems that the movement of persons is orchestrated to reinforce the camera movement. The shot grows out of the previous scene, through a very slow dissolve that underlines David’s disorientation. The way the dissolve makes it appear that he is emerging out of his own body lends a feeling of an out-of-body experience. The pirouette the Steadicam will do in the shot is a metaphor of his dizziness.

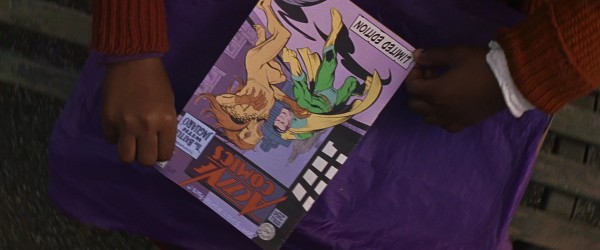

One of the most innovate moments of the film also has to do with a camera pirouette:

The staging of the scene is meaningful in so many ways. The spinning camera reflects the dizzying feeling of Elijah’s life-changing discovery. The movement which not only fetishises the comic book, but does it in a very odd way, reflects the unhealthiness of Elijah’s soon-to-come obsession with comics. The strange way that the comic for a while remains fixed, despite all the turning that goes on, reflects how comic books will always be Elijah’s safe haven – where everything falls into place – despite all the turbulence and “movement” of his life. Finally, delaying the full view of the comic is part of Shyamalan’s strategy of heightening tension by holding back information, discussed some more here. (These two pirouettes form one of the many connections between David and Elijah, discussed here, and it is worth noting that both pirouettes take place after accidents – Elijah has just broken an arm.)

The most dramatic episode of Unbreakable comes when The Orange Man pushes David from the second-floor veranda into the swimming pool. Even though the shot only lasts three seconds, and just an unspecified blur would have done the job for most moviegoers, Shyamalan is determined that the shot shall be consistent with what a person would see, doing a somersault while falling:

But the Shyamalan accuracy does not end with this (some of the following frames are very dark, but legible if you enlarge the image by clicking on it):

Many directors would have just shown David landing in a wider shot and then cut to a close-up, the camera aligned with an actor already lying down, followed by some short, chaotic shots of the surroundings he is looking at. The precision- and coherence-oriented Shyamalan, however, even at this micro-level wants to combine landing, David getting his breath back, and his looking around in a single, longer shot. As for precision, capturing his face after landing was almost perfect to begin with. Even though it is a bit hard to determine, on top of it all he seems to pull his usual intensifying trick by closing in David’s face slightly between the two last frames above.

He also wants to stay local with David. For the viewer does not really understand his predicament until the dramatic shot below, which employs the revealing-through-camera-movement of which we gave many examples above:

Soon David goes under, and the following underwater cinematography should also qualify as camera gymnastics. (Shots from underwater also figured heavily in the ending of Lady in the Water.) Even though very few in the audience will be able to fully grasp it – among all the chaos of a frantic David fighting to extricate himself from the tarpaulin, with sudden black-outs of the shots and an abundance of bubbles – the shots are consistent here as well:

To the observant viewer – the shot lasts only about 1.5 seconds! – showing The Orange Man like this provides an explanation why the children are allowed time to rescue David (and why David is later able to surprise him). Shortly afterwards, we get several glimpses out of the water again:

The colours of the clothes match, so the vague shapes seen in the underwater shot just before are clearly the children. Even though the underwater shots are dominated by drama and desperation, visual chaos, disorienting cutting, and a cacophony of sounds, Shyamalan wants these scenes to narratively hold up to the scrutiny an observant viewer. Many directors would have been satisfied with representing David’s experience of chaos with just chaos, but Shyamalan insists that there should be a narrative line there, explaining, at best subliminally, but very specifically what The Orange Man and the children did. Many directors would also have cut away, out of the water, to clearly show what the others did, but that would have spoiled our immersion in David’s experience and also been at odds with the somewhat constricted viewpoint of the film.

We round off this chapter with a quick note on the consistency angle: When David steps out on the veranda, in a very short glimpse the layout of the area where he will fall is visible:

Lateral camera movements

Typical for Unbreakable is the following 32-second shot, which even more typical for Shyamalan follows a geometric pattern:

The lateral travelling shot is one of Shyamalan’s most characteristic devices. Like the long takes we shall discuss later, they are an important weapon in his strategy of creating fluidity and coherence by combining many narrative elements in the same take. They also exert a stylisation effect on the film.

We have already seen one in the third rejection, and some will turn up later. They crop up when you least expect them, for example gliding emphatically along the weightlifting bar in the weightlifting scene. Here are some more examples (the first one is also quite close to being an overhead shot):

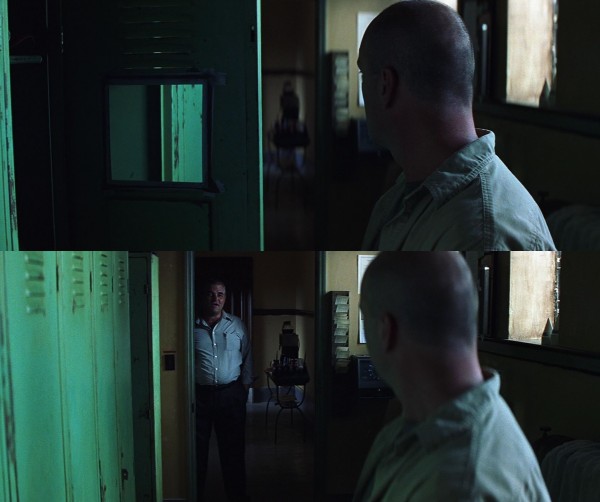

Block and reveal

An entirely new development in Shyamalan’s stylistic armour compared to The Sixth Sense is a stylised form of revealing plot elements. We just saw an example, and there were many more earlier, of the more traditional way of pulling away the camera to reveal salient elements and objects. We are so used to this in cinema that it feels quite natural, but the method we shall now explore feels more artificial and self-consciously staged. It fits snugly, however, with the more ceremonial nature of Unbreakable. The method involves a static camera and the revealing happens through removing objects or people.

This example is slightly different, with the blocking figure remaining motionless:

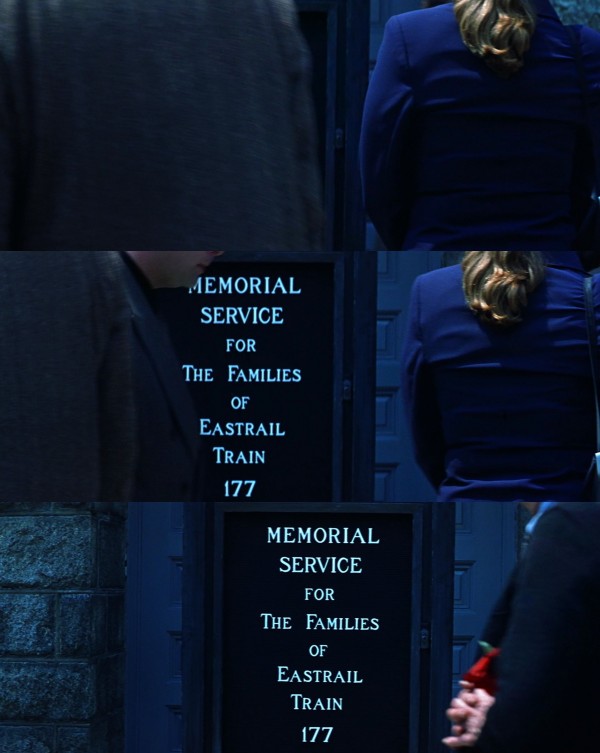

Here David’s reason for being at this location is gradually revealed, from behind people:

This revelation involves some slight camera movement:

Another variation: The camera is motionless but something is lifted directly into the shot:

The most majestic revelation process of Unbreakable happens when David enters the train station, where the revelation is caused by a combination of David moving forward and the camera rising behind him. The shot is staged as if it were part of some strange ceremony:

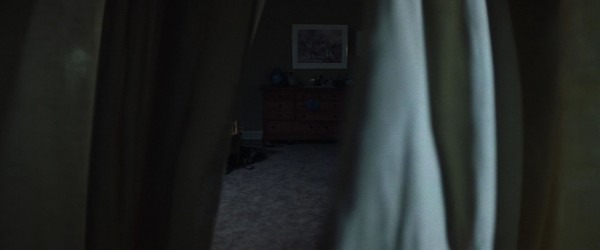

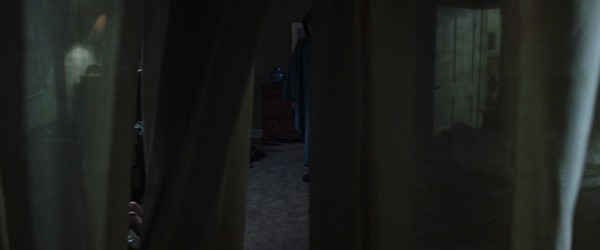

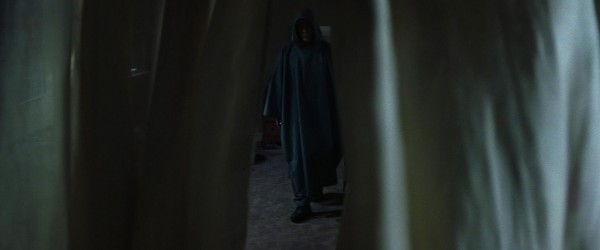

The most ingenuous and innovative revelation scene is undoubtedly the following, where the camera is static and the curtains in the foreground are used as cutting devices (one can only imagine how many takes were required to make this 45-second shot work properly):

This entire sequence with The Orange Man and the house is orchestrated with an otherworldly quality. David moves through the house as if part of a slow nightmare, gradually uncovering its perverse events and secrets, in an atmosphere of quiet dread, with faint sounds from the murderer rummaging somewhere in the house. At the same time, the absence of film music and the sobriety of the mise-en-scène lend a realism to the proceedings that only increases the sickening atmosphere. The first part of the sequence culminates with the above curtain shot, which in brilliant fashion conjures up an atmosphere unlike any other film. It has an air of a medieval ceremony: David’s hooded raincoat makes him look like a monk, and the woman is a human sacrifice. (If you want to follow the sequence in its entirety, we covered the start in the second article, here, and we have already discussed what happens afterwards here.)

Tight framings

In possibly its strongest formal connection to the comic book medium, Unbreakable shots’ salient information is sometimes restricted to a smallish section of the frame, while the rest remains static, containing only “dead” information. Thus, in the curtain scene just above, the shot is divided into steadily shifting salient sections, while the rest of the image is obscured. While frames within the main frame of the shot is a common method to direct the viewer’s attention and enhance pictorial composition, this salient section resembles a single comic book panel. Uniquely used for Unbreakable among the five Shyamalan films we discuss here, CinemaScope of course lends itself to this policy, creating a broader canvas in which the sectioning will be more noticeable.

Overhead shots

The overhead shot is a Shyamalan mainstay and is employed in one of the most enchanting moments of the film, accompanied by a tender, tantalisingly wistful version of the main theme of the film music:

David’s visions of the perpetrators are all filmed from a high angle, and so is his climatic battle with The Orange Man, as if he himself has entered one of his horrific visions. In this regard, it is interesting that after the end of David’s vision of The Orange Man, the camera abruptly rises so that he is shot from a high angle, as if in foreshadowing of his upcoming battle:

A couple of times (included below) the battle enters an almost full-overhead angle. The following slide show exhibits various overhead shots:

Upside down shots

A specialty designed for Unbreakable, one of its most distinct formal motifs is shots where either a character or an object is shown upside down in the frame:

The pivotal nature of Elijah’s confrontation with the gunman is underlined by the strangeness of the upside-down motif:

The following slide show exhibits other instances of this type:

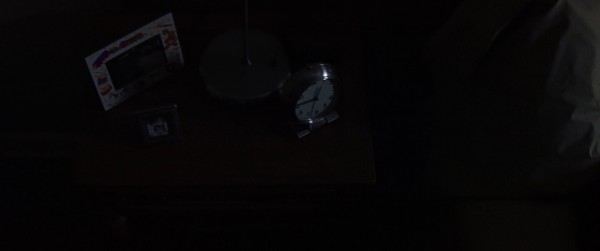

Except for the comic books, there is a pattern that this type of shot serves as a harbinger of, or connector to, accidents: The little girl on the train before the crash; Joseph and the TV screen before the news of the crash; the sign on the fence before David revisits the train wreck, leading further to the car accident flashback; Elijah and the gunman just after Elijah’s accident. The upside-down placement of the car is the nucleus from which this strand emanates – which is only natural since this accident is the root of David’s later problems in life. Before Joseph turns over in the sofa, even the news report itself is upside down:

(While discussing the train scene in the second article, we saw that the upside-down motif also connected the little girl to David’s family, and also to comic books, which again connected her to Audrey – a good example of how motif strands can serve several purposes, branch out and combine with other motifs and elements. Another combination of strands is in the image above, which combines the upside down and overhead shot, the latter in the news footage, “masked” by the position of the TV set.)

The only upside-down shot left to examine (below) does not fit the accident pattern, but it is of a rather different nature: David’s point-of-view shot when he is lying down in the weightlifting scene, it is much less centred and deliberate:

Foregrounding and staging in depth

What feels realistic and “normal” to a film viewer is often dictated by the degree of correlation between what is seen and how an individual might watch the same situation in real life. (An exception is the rather strange case of how a shaky camera, lots of close-ups and an insistent following the characters around have for many years now come to signal a certain raw, everyday realism.) Virtually every device we have so far examined, however, flies directly in the face of realism. The same goes for the last device under discussion, namely shots with a heavy foregrounding of elements and/or an extensive exploitation of the depth dimension of the shot. Please allow me to revisit a couple of shots already discussed from other angles:

The following composition has less spatial depth, but an object is again heavily foregrounded. The shot also exemplifies another important feature of Unbreakable, namely a low-angle camera position:

The following 72-second, fixed-camera shot is a nice example of how foregrounding and staging in depth can create a stylised effect, which in turn can lend, in an almost subliminal way, importance to the moment (for another subliminal effect in this scene, through colour, please have a look here):

The opening scene of Unbreakable is deliberately disorienting and also the film’s most complex depth dimension shot. We briefly discussed that before too, as a tight framing, and the salient part of the action, between the curtains, takes place in deep space, and already here people are grouped so they create several levels into the depth:

The bigger mirror is employed to play yet another variation on the depth game:

This ingenious trompe l’oeil scene will play out for a long time, with the camera constantly panning either to the right to show the “real people” or to the left to show their reflection in the mirror. The naturalness of sight lines and camera movements is shattered in this confused space – Elijah’s mother looks at and speaks to someone to her right, but the camera will often move in the “wrong” direction, to the left to catch the response in the mirror. Shyamalan elaborates further on this set-up by having the characters sometimes look at each other through the mirror:

Of course the viewer will quite soon get the scene’s general narrative drift, but working out all its visual ramifications is not that easy. The placement of the characters seems to form an arc that continues into the mirror and further into its depth dimension. The disorienting mise-en-scène is obviously a reflection of the film’s plot of things being not what they seem. (Trivia: The name tag of the saleswoman, played by Johanna Day, reads Gretchen Rau, which seems a jocular nod to the film’s set decorator.)

Depth dimension types of shots are virtually everywhere in Unbreakable. If you page through this article, you will see that almost every shot in every chapter (except the “upside down” chapter) is playing around, one way or another, with the depth dimension. Several also feature heavy foregrounding, for example The Orange Man’s victim and the fluttering curtains. The following is a slide show of some other interesting shots not yet covered in this article:

Long takes and cutting in camera

A common thread for all these articles on Unbreakable is that the film is drenched in various forms of coherence, through all kinds of character parallels (the first article), recurring motifs (the second) and recurring formal devices (this one), weaving back and forth, often combining, in constantly shifting patterns. The long takes and their sweeping up many narrative elements in the same brushstroke can be said to be part of a similar strategy of coherence.

Considered as a mainstream Hollywood film designed for mass-market appeal, Unbreakable is probably unique. In the first article, we discussed how it is, as such, virtually an experimental film, and this impression is reinforced when we consider its abundance of very long takes. Its average shot length (excluding logos, credits and end credits) is no less than 18.9 seconds, which is in the same range as Antonioni classics like L’avventura (1960, ASL 17.7) and The Passenger (1975, ASL 18.6). Many scenes consist of only one take. (If one recalculates the ASL after excluding the fast-cut suspense sequences – the chase sequence (full analysis here) and the scene where David is pushed from the veranda and nearly drowns, excluding the long take where he emerges from the swimming pool – the result is 22.3.)

This breaks down to:

- 61 takes of 30 seconds or more (25 takes in The Sixth Sense)

- 22 takes of 60 seconds or more (10 in The Sixth Sense)

- 8 takes of 120 seconds or more (1 in The Sixth Sense)

The longest takes are

- David attempting to seduce the woman on the train (229 seconds)

- the bar conversation between David and Audrey (174) (single-take scene)

- the car accident flashback (140) (single-take scene)

- the stadium top conversation between David and Elijah (132) (single-take scene)

- the kitchen situation with Joseph and the gun (129)

- Elijah reflected in the TV screen talking to his mother (129)

- David in the emergency ward (126) (single-take scene)

- the opening scene of Elijah’s birth (126) (single-take scene)

The nature of these long takes, however, is highly diverse. The stadium top conversation and the bar conversation feature very slow camera movements, respectively moving away from and closer to the characters, especially in the latter case with hypnotic effect. The camera in the TV reflection shot also dollies away, partly to connect to the arch motif. The emergency ward shot is recorded mainly with a studiedly fixed camera.

Other long takes function, in a sense, as a linking device between essentially separate shots. Shyamalan is “cutting in the camera”: in the last part of the single-take hospital reception scene – at 111 seconds too short to make the above list! – the camera homes in on hands or close-ups of the various characters. The kitchen shot also cuts back and forth between the three characters. At other times, the very “continuousness” of the separate-shot parade and the elegance of its execution lend an undercurrent of mystery and importance to the proceedings. In the 45-second curtain shot there is a new “shot” every time the wind blows away the curtain to reveal various parts of the room.

But the prime example is the train scene (furthered discussed in the second article here and here.) The camera placed in the row of seats in front of him, it starts with David by the window. Then the camera makes a stylised lateral movement towards the middle of the row to catch him between the seat (as depicted above). Then he exchanges glances with the little girl occupying the “same” seat where the camera is placed. Now it is time for the film’s longest shot of 229 seconds (3’49”). It begins with him reacting to the little girl (the first “shot”), then the camera travels laterally back to the window again – this kind of formal echoing is pervasive in Unbreakable – where he sits (second “shot”) until a voice distracts him. This is the signal for the camera to return to the middle (in a more rapid, less stylised way) to capture the young woman about to sit down beside David (third “shot”). For the rest of the take the camera will move, in a slow and lightly hypnotic manner, between two angled positions, looking at either David or the woman, like this:

When the take ends with another echo, a cut to the little girl, it has consisted of as many as 18 “separate shots”. In yet another echo, we have seen David both take off and put on again his wedding ring, in a strict pattern of lowering the camera from his face, down to just concentrating on the hand and ring, and return to his face, which could be said to create even more “shots”. In addition to the technical challenge of staging the take, Shyamalan has also managed to orchestrate several pauses, where credits are portioned out, elegantly and non-obtrusively, while the pauses in themselves feel narratively natural, even meaningful.

An even more mesmerising scene is the first meeting between David and Elijah, where the latter’s smooth rhetoric attempting to lure David into his world is accompanied, in the early part of the conversation (shot 2-4), by a highly stylised lateral camera movement and two hypnotic closing-in shots. Here individual shots are not of monstrous length, but the effect is sort of cumulative: the whole scene lasts as long as 5 minutes and 9 seconds, but consists of only 8 shots, respectively 31-55-62-34-31-31-7-58 seconds (the last one being the first rejection).

Immersion

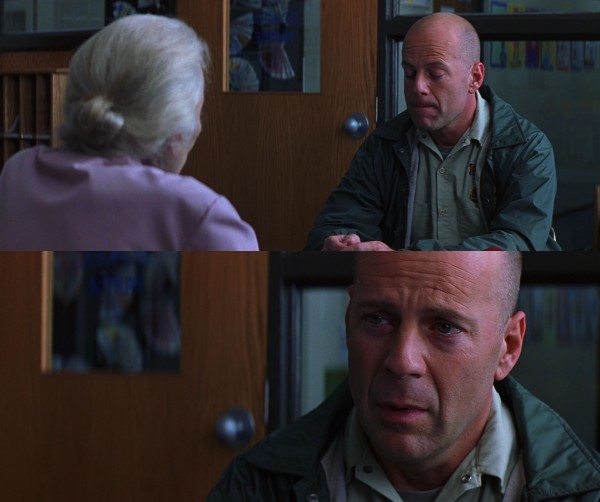

Even with all the long takes, there is little feeling of being a distant observer in Unbreakable. Close-ups are a device that encourages immersion and identification. Unbreakable has its fair share, but not seldom as part of a longer take, like in the stadium scene when the shot elegantly turns into a temporary close-up of David in the very moment he senses that there is a gunman in the queue. The school nurse scene is concluded by a 109-second shot that, very slowly, turns into a close-up – at the same time charting David’s process from childish sheepishness to childish apprehension, as she reveals the story of his childhood drowning:

There are also many point-of-view shots, with their potential of drawing us into a position of character identification. One reason for this is that Shyamalan’s long takes sometimes are of a chameleon-like nature, shifting between various states. For example, during the pirouette of the hospital reception scene, the shot twice turns into David’s POV shot, and both when David is following The Orange Man in the train station and Elijah into the inner office in the epilogue, the shots are weaving in and out of being David’s POV. Interestingly, one of the most suspenseful scenes of Unbreakable, David’s entering the home that The Orange Man has invaded, has, except for the swimming pool interlude, only one POV shot, when David has opened a door and sees the two bound children. Part of the dread of this scene is obviously not meant to be created by immersion, but by being a helpless observer of David’s movements in this otherworldly hell-house.

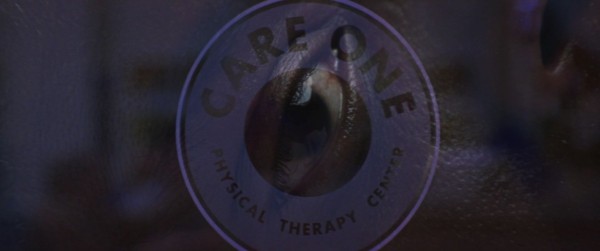

Elijah is involved in no less than two POV shots that metaphorically transcend time and space. We have already discussed the elaborate camera movement that makes it look like he is gazing directly from his hospital bed into the physical therapy centre. And consider the transition between the time planes of the 13-year-old and the grown-up Elijah (discussed more here), which also contains an innovative use of reflections and POV:

Unbreakable is such a dark and serious film, so it feels nice to be able to end this article on a note on levity:

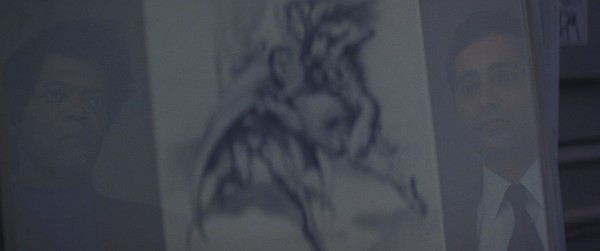

Lecturing the customer (on the right) Elijah says, “Notice … the slightly disproportionate size of Jaguaro’s head to his body. This again is common, but only in villains.” It has been noted that Elijah’s hairstyle (based, exaggeratedly, on civil-war era activist Fredrick Douglass) makes his head seem quite big, thus foreshadowing that he will be revealed as the villain of the piece. In the first article, I discussed the epilogue and Elijah’s mother saying “See the villain’s eyes? They’re larger than the other characters’.” At the time, I thought that her own quite large eyes, being Elijah’s mother, was yet another harbinger of his villainy. But while taking the above frame grabs for this article, thinking about eyes and seeing, because of my recent idea that this was a POV shot across time planes, suddenly something clicked. From time to time during earlier viewings, I had noticed something odd (at 25:08 on the Blu-ray edition) about a quick glance Elijah sends to the customer:

The effect is much more evident if you watch the film, but as soon as Elijah looks at the customer, something very strange happens to his eyes: they make an odd rolling motion and turn enormously, comically big! It might be easier if one compares their faces:

It is still hard to see, but the eyes in the middle image, his “normal” state, seem about as big as when he gets in focus at the end of the shot. This is certainly as good an illusion than any of the “magic tricks” in The Sixth Sense. Is there some sort of distorting lens applied, perhaps in conjunction with Samuel L. Jackson being ordered to be as wide-eyed as possible? Or is it some digital effect? Or just a distorting quality of the pane? (His head seems also slightly elongated when he is out of focus – to make his head seem even “bigger”?) Elijah’s mother follows up her eye remark with, “They insinuate a slightly skewed perspective on how they see the world – just off normal.” “Skewed” can also mean “looking askance” (or even “distort”) and that is exactly what Elijah does in his sidelong glance, his pupils comically at the edge of the eyeballs. What his eyes most of all look like is those of a character in funny animal comics – after all, this is a film about comics! – as if Unbreakable for just a second has turned into Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

Anyway, whether it is just an accident or M. Night Shyamalan, under the cover of the out-of-focus conditions, has decided to pull an audacious joke here, the effect is the same: an absurd (and for all practical purposes invisible) way of using both big eyes and head to foreshadow Elijah’s villainy. When one has seen a film 23 times and stumbles upon such things by accident, one really starts to wonder about what else might be hidden in these films.

Unbreakable may not have such an immediate emotional impact as The Sixth Sense or The Village, but it is his most formally sophisticated work. Many shots that seem almost minimalistic turn out to have hidden depths on closer examination. The film is inventive and complex yet executed with grace and simplicity. “If my house was burning down and I could run in to get two movies, I’d go get Unbreakable and Lady [in the Water]. I don’t know why; maybe they are more me than anything else.” —M. Night Shyamalan.