The Village, Part I: Motifs and story arc

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the first article about The Village. The second is here, the third here. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

Writing about such a complex work as The Village is a challenge not only in analysis, but organisation. Unlike the other films in this series, the general comments on The Village must wait until the second article, to keep this first expedition into Covington Woods at a manageable length. It is more important to get across the greater picture of the film’s story arc and to present its supporting array of motifs. Since they will be constantly referred to in the later articles, it will be useful to have them under the belt at an early stage.

This article will start out with the first few minutes of the film, introducing the reader to its basic situation, symbolic world, general atmosphere and presenting a foretaste of its intricacies. Then we launch into the motifs, with numerous examples, the vocabulary of the secret language expressing many of the films’ underlying meanings. (Table of contents: colours, hands, doors, chairs, numbers, walls, other motifs). Eventually we pick up the story after the climax of the quest into the woods, to delve into the end phase of The Village. (Table of contents: secret box, meeting Kevin, guard shack, leaving Kevin, last shot).

Along with general interpretation, there is a special emphasis on how the ending interacts with the rest of the film: closure of thematic and motif strands, various echoes and parallels – in short, how the film is a living organism in constant communication between its various parts, transcending linear narrative so that each moment may at any time recall or foreshadow other moments, creating new meanings and metaphors. Throughout, the backbone of the analysis is frame grabs from the film.

There are three addenda. The most important is addendum A, raising significant questions about the ambiguous final state of the village. Addendum B is about the time period and other practical questions about the village. Addendum C presents the full text of the four “death stories”, about the violence that led to establishing the village.

The second article will discuss the film in general and explore its character relationships. The third one shall analyse two sequences: the murder attempt and the quest into the woods, as well as the important motif of wind/breathing. The fourth one will examine visual style and deal with odds and ends.

*

In order to discuss the film properly, I will have to reveal the whole plot, including the plot twist at the end, beginning immediately.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of The Village, here is a brief outline of the plot. There are several slide shows. Each show can be restarted from the beginning by clicking on the current image to enlarge it and then return to the article. There are also links to various points inside the other Shyamalan articles. Dependent on resources, on occasion web browsers will miss the exact target point on the first attempt, since images are loaded after text, which may cause a shift. If you do not reach the expected point in the other article, try again, then the browser will meanwhile have corrected itself.

Starting The Village

The first shot of The Village presents a range of its signature features: pastoral setting, lingering pace, highly distinctive formal language and the role of rituals.

Accompanied by a soft lament in the film music – a close variation graced M. Night Shyamalan‘s name in the credits just before – a gathering stand at respectful distance from a grieving man. During the 36-second shot the camera is slowly closing and (finally also) zooming in. The windy conditions – wind as a motif will be explored in the third article – and especially the rustic surroundings are allowed to sink in.

The opening shot also illustrates the basic premise. The Village is about a collection of people having withdrawn from the world, behind a double set of perimeters: (1) a high wall surrounding what the outside world thinks is a large animal sanctuary, and (2) inside that area, a line of tall stakes marking the border between the valley of the village and a sinister forest around it, where terrible creatures are supposed to roam. In the opening shot the distant man inside the graveyard is visually fenced in, and he is alone (representing the village) in contrast to the large body of people (the outside world). The elders who established the village did it as a defense mechanism after the traumatising deaths of their loved ones, echoed here in the withdrawn man burying his son. Their place of retreat has in many ways become a prison, however, hence the visual appearance of the fence.

The coffin encapsulates his tragedy, in direct parallel to the mysterious boxes possessed by all the elders, containing items about their pre-village lives and details of the unbearable violence against their families. Furthermore, many scenes are shot from inside the villagers’ houses, with the camera pointing towards doors, as if to establish their dwellings as yet another set of perimeters, inside which the villagers hide. So we have this chain of ever-constricting areas-within-areas: “the animal sanctuary”, the valley of the village, the houses, and the boxes of secrets – the latter both representing the aching heart of the villagers’ traumas and their denial of them, by locking away everything to do with the outside world.

In concert with the music, there is also a lament in words, the mourner speaking almost inaudibly. (Note how virtually all the lines could easily have been spoken by the dead son about this father instead, emphasising the tight bond between family members in the village, and subtly increasing our sense of the depth of the father’s grief.)

Who’ll pinch me to wake me up?

Who will laugh at me when I fall?

Whose breath will I listen for

so that I may sleep?

Whose hand will I hold

so that I may walk?

On “whose hand…” there is a cut to the next shot and a rise in volume. First the camera maintains the stillness that concluded the first shot, binding the shots formally together, and then, in equally stylished fashion, it is lowered towards the man. Throughout, there is ample use of hands against the coffin – hands are perhaps the most important motif of the film. We also see his wedding ring, indicating that he is now alone in life – there is no one there to mourn with him, not even a wife. Like in the first shot, he is again isolated and boxed in, by (from the top clockwise) the coffin; the shadow and gravestone; the grave; the shadow and fence.

The third shot breaks with the previous serenity, probably to represent his raw grief, with an unruly hand-held shot moving from the statue down to the gravestone. But it continues the trend of ending up ever-closer to the man. We are never allowed a proper look at his face in this scene, however, neither those of the spectators – emphasising the village as community. There are also nice visual echoes: the statue is bent forwards like the mourner, and in the arcs of the statue’s foundation and the gravestone. Its arms are crossed as if it protects itself from external threats, like the villagers.

The gravestone yields interesting information. We learn that the man is named August Nicholson. The son died a 7-year-old, like the girl in the news in the guard shack scene near the end of the film. The girl was murdered, the boy died of illness, but the parallel underlines that withdrawing into the village cannot prevent the untimely death of their loved ones. The stone also declares the year to be 1897. (Addendum B discusses why stating this year is not cheating on the audience, along with other practical issues about the village, including the imperfect usage of old-fashioned vocabulary and speech patterns.)

Over the shot of the tombstone we hear the voice of another person say: “We may question ourselves at moments such as these,” and the next shot reveals that he is talking during a funeral gathering of the villagers. He continues: “Did we make the right decision to settle here?”

August touches his hand reassuringly, but seen in conjunction with his hand on the coffin, it also means that the village is now his only family. This is the beauty of motifs – our awareness of them unveils additional meanings. The camera rises to take in the speaker, who is later revealed to be Edward Walker, the ceremony master and de facto leader of this community. With newfound strength he concludes: “We are grateful for the time we have been given,” a ritualised saying, for it is repeated during the wedding later in the film. The shot composition at the end is revealing: Edward is a towering figure (of the village), he is embodying the massive solidity of the town hall, and the tree represents the dangerous forest surrounding the village, here in a tamed version due to the civilising influence of this community.

The next shot is of a child, who appears not simply due to her photogenic beauty and innocence – although the selection of extras and minor characters for this film is a splendid collection of distinctive features – but a subtle manifestation of an issue just hinted at in the film, gently underlined by her downcast expression. “We are grateful for the time we have been given,” alludes to the fact that the elders have doomed the life expectancy of the village’s second and third generation to late-19th-century levels. (Born in the 20th century, the elders themselves are vaccinated against common diseases.) Later, Edward refers to his shame upon hearing that “my daughter’s vision had finally failed her, and that she would forever be blind,” because Ivy’s sight might have been saved with 20th-century medicine.

The harmony of the gathering is soon disturbed by distant howling from the creatures in the woods, but while the rest look worried, one of them reacts with great merriment. This young man is as much a child as the girl we just saw. This is Noah, the first to be introduced of the film’s three most central characters. Ivy and Lucius are nowhere to be seen during the funeral – Shyamalan obviously wanted to save their first appearances for later, for maximum impact.

At first glance, Adrien Brody‘s performance might seem like an exaggerated, rather inane idea of the random behaviour of a “madman” – or “village idiot”! – but further viewings will reveal that all his actions are fully explained as a reaction to having seen through the elders’ story about the creatures. Noah knows perfectly well it is all make-believe, a ruse to prevent the villagers from contacting the outer world. He is simply thrilled by the fun of the spectacle and the fear it instills in the others. In this light, Brody’s acting is quite brilliant, precise and engaging. His character arc reaches peak resonance in the unbearably tragic scene where he sits in the rocking chair on the porch with bloodied hands after the murder attempt on Lucius (see the third article).

During the current gathering he is disappointed that the howling ends so soon, a subtle hint of his upcoming idea to cause more “action” by killing animals and playing a creature himself. One could say that the elders’ secrets and manipulations are the underlying reason for his transformation from innocent child to murderous madman, for Noah will eventually reintroduce violence in this peaceful community. (In this respect, it is interesting that Alice states the reason for her secret box to be “…so the evil things from my past are kept close and not forgotten. Forgetting would be to let them be born again in another form.”)

The funeral contains another harbinger of future events. The open grave is reminiscent of the big pit into which Noah-as-creature falls in the film’s dramatic climax, not only through its darkness and connection to death, but also the demise of someone’s child (and Noah is just a big child). Finally, both children die because of illness, as a consequence of the elders’ rejection of modernity – as Lucius wonders at some point, Noah’s mental problems might well have been treatable with medicine from the outside world.

Colours

The red cape of the creatures is a brilliant stroke. (Actually it was a last resort, late in the production, since the original creature design did not work at all.) It plays beautifully not just together with the villagers’ notion of red being the “bad colour”, but also in interaction with the “safe colour” of yellow, in the cloaks that are used on guard duty in the watchtowers or when performing tasks near the village border. (Yellow, the colour of cowardice, is a great fit for the fearful villagers. Even though suggested by many, a connection to the US terror alert codes is not obviously meaningful; yellow is not a safe colour there.) Especially during the long quest sequence through the woods, the figures clad in cloaks in feverish red and yellow, seen against a barren landscape devoid of colour, take on an air of being elemental forces struggling it out in a symbolic arena.

When Ivy is introduced in earnest, her uniqueness is signalled by a blue dress, a colour hardly used by anyone else in the village. To lend even more visual punch and mystique to her introduction, she is shown in two clearly marked, stylised positions, frontal and in profile related to the camera. When she is “re-introduced” at the start of the quest by appearing for the first time in the cloak of the “safe colour”, the stylised positioning is reversed. Her red hair is, of course, one some level also interacting with the film’s colour scheme. (Curiously, her “helmet” of hair is replaced with a yellow hood.)

The second article will chart the many parallels between Ivy and Lucius, but as regards colour it is interesting that when Lucius too is first seen in a yellow cloak, a similar frontal/profile pattern occurs: he is approaching the camera frontally, stops, and then turns into a stylised profile position on which the camera will linger.

Then Lucius goes into the wood to get some berries of the forbidden colour. The raging clash of red and yellow – studiously arranged to maximum effect as the climax of an ingenious camera journey – is then repeated in the stunning moment when the camera pulls up to reveal that Ivy has stumbled into an area overwhelmed by the “bad colour”.

This type of berries was introduced when Noah playfully put them into Ivy’s hand during the Resting Rock scene. Later, during the high drama when the creatures invade the village, Ivy is stretching out her hand in expectation that Lucius will come around to grasp it. In an unforgettable moment, it seems as if a creature seen in the distance is walking on top of her hand. Then both the camera and the creature close in on her hand, in a crescendo of convergence of the red and hand motifs.

Hands

This brings us to the most important and pervasive motif of The Village. We have already seen August’s hands against the coffin and pressing Edward’s hand during the speech. These are unobtrusive instances, however, and surely human beings must be allowed to use their hands in a movie…? But The Village provides an enormous number of enabling moments to do with hands, thus encouraging us to pay special attention to hands throughout. (Ivy’s blindness, in part compensated for with touching, might be an underlying reason for a hand motif.)

Furthermore, a comparison with the previous films in the Shyamalan pentalogy will yield no particular emphasis on hands and touching (although an important strand in Signs links the alien signals received by the baby monitor to the family bonding by touching each other.) On the contrary, a major concern of those works is the gulf between people, whereas The Village strives mightily to express harmony and closeness between its inhabitants. (For a look at another film immensely serious about hands, see my analysis of Spielberg’s Munich [2005] – in Norwegian, but its heavy use of frame grabs should get its point across; jump directly to the hands chapter here.)

To linger a bit on Unbreakable, hardly any characters touch each other. It is difficult to think of a more reluctant and halfhearted embrace than the one between the spouses in the hospital reception. The hero carrying his wife up the stairs near the end is a notable exception, but even the final reconciliation between father and son happens with all three family members spread out in the kitchen. Ironically, the hero’s all-important visions are set off by touching – but very lightly! – unknown people. And when he finally touches his nemesis, the result is literally shattering:

Getting back to the outstretched hand during the creature invasion, it is followed by Lucius dragging Ivy inside the house towards the safety of the basement. Later in the narrative, during the sudden commotion after the wedding dance has been interrupted by screams, Ivy is thrusting her hand towards the lens. Then the same pattern occurs: in a situation where Lucius is nowhere to be seen – he has been absent during the festivities – he suddenly turns up to tow her away towards safety.

The first situation is obsessed with hands. First her hand was dominating the shot, then his hand grabs hers, and after the above shot of him dragging her along, there is a cut to their intertwined hands. Down in the cellar, their hands are raised to be clearly seen in the shot, before the scene finally ends with their intertwined hands dominating the image. The key points are presented in the following slide show:

When the village is in an uproar because Noah has been found “with quarts of blood upon his clothes and hands”, Ivy storms off towards Lucius’s house:

When Ivy enters “the old shed that is not to be used” to discover the red creature cloaks hanging there, again the scene is obsessed with hands, also this, like in the creature invasion, connected to an open door:

On her quest through Covington Woods she falls into a pit, probably created by an uprooted tree:

When Lucius fell in love with Ivy in childhood, he stopped touching her to hide it. (Of course, this made the intelligent Ivy guess his feelings.) In the same way, Edward Walker never touches Alice, Lucius’s mother, with whom he is secretly in love – an inversion of the motif. During the wedding Alice decides to test her son’s theory:

As usual, with the application of motifs and patterns in a film, lots of naturally occurring actions turn out to be meaningful echoes of each other. Here are the two quiet room scenes:

Here are instances of the hand motif in connection with special moments, often introductions. When Lucius saved Ivy from the creature by clasping her hand, it was the first time he touched her in the film (probably the first time since childhood)…

Below, Alice tries to scare her son from going to the towns by telling him for the first time how his father was brutally murdered there. In this scene Lucius helps her wind up some yarn, but he ends up looking entrapped by it, by his hands, characteristically enough for this film. The thread might also represent an umbilical cord, with Alice reeling in her wayward, eccentric son, domesticating him so to speak, fittingly by something as prosaic as yarn. (Is there also a pun? While the story of his father is real enough, the big lie of the village’s relationship with the outside world is a “yarn”.)

In addition to the hand business in the last shot, here is a slide show of some final hand moments:

Doors

Doors are of course an ideal motif since they naturally occur in most man-made environments and, if the filmmaker should so wish, with ready-made symbolic connotations: portals to others dimensions, or to new stages of life, or the possibility of attaining new understanding. Shyamalan used doors extensively both in Signs (here, for aesthetic purposes or underscoring the threat of aliens breaking in) and The Sixth Sense (here and here, often in connection with ghost appearances). In the current film, as a mark of its importance the motif is used to set up an important visual rhyme near the end (here) and features prominently in its last moment (here).

Also here there is a convergence with the colour motif, for the morning after the invasion all the doors of the village have been marked with red:

Doors are sometimes used to help storytelling by avoiding cuts in long-take filming (a villager discovering the tragedy inside) or to lyrically frame characters to make them seem almost mystical apparitions:

A door is used to particularly understated intensifying effect during the long, 142-second take as Ivy and Edward approach “the old shed that is not to be used”:

In the bitterly tender “It is all that I can give you” scene between Alice and Edward (see the second article) there are both an open and a closed door. Since the underlying issue of the scene is a common recognition that their mutual, secret love can never be acted upon, one might say that the doors are cancelling each other out. The open door, always physically connected to Edward in the shot, may mean that when he uses it to leave her home at the end of the scene, he will also use it to walk out of her life. The closed door connected to her could symbolically mean that she cannot ever follow after him to pursue her love.

In the below slide show, doors (and one window) are used as framing devices that become integral to the dreamily mysterious lyricism of one of the film’s best scenes: a montage of three almost wholly symbolical shots where the villagers enter the frame, seemingly in slow-motion, as they discover skinned animals strewn about.

During the creature invasion, Ivy’s doorway position is shot both from the back and front (with lamps both in nice symmetrical placement and as a central halo):

After Lucius has grabbed her hand, the now closed door remains central to the shot (and after they have escaped into the cellar, the camera lingers on the trapdoor):

Doors are extremely important in the murder scene and its aftermath, but since this sequence will be analysed in the third article, a slide show will suffice:

The two quiet room scenes follow the familiar The Village scheme of being inside a room looking out at the environment through a door. Shyamalan is setting up a visual rhyme, with the scenes starting from the same basic camera positions, and ending outside, with the camera gazing towards a closed door. But the situations are extremely different. The first scene ends in friendly harmony and freedom, and a wild footrace to the sunny Resting Rock. The second one ends devoid of people and with Noah desperately banging on the door, trapped inside:

We shall end with a slide show of other door scenes, where the motif is a bit more passive (we also include the watchtower trapdoor through which the first creature of the invasion can be glimpsed):

Chairs

By now, it ought to be quite clear why the chair was so ominously placed in the first quiet room scene, with the camera even sliding from right to left to include more and more of it in the shot. It foreshadows of the tragedy to come and Noah’s future position in it as an attempted murderer:

Chairs in The Village are often connected to loss, with an empty chair as a reminder of the absence of a person. This is not uncommon: Hou Hsiao-hsien in his partly autobiographical film A Time to Live, a Time to Die (1985) showed an empty chair as a moving reminder of the dead father who loved to sit in it. In the below scene, Alice has just told Lucius how his father died. The chair represents the memory of the father, but at the end of the scene it also symbolises his mother’s absence in the shot, a result of their inability to communicate:

As we shall see, chairs become a secret language:

It is worth noting that when Ivy is introduced she is sitting on a bench. If anyone is still in doubt about the importance of chairs in this film, consider this publicity shot, featuring the director, from the extra material on the DVD:

Harmony in numbers

This is a curious motif. An analyst must go where the data lead, however, so since the pattern is definitely present, it cannot be ignored. The Village portrays an exceptionally tight community, marked by solidarity and harmony. Very often people are seen in pairs, and it is natural to assume this to be a gentle visual emphasis of harmony. (Lucius the loner is a notable exception, see the second article.) But there also seems to be a pattern of people grouped in fours, eights or even twelves. (Shyamalan has previously shown an obsession with numbers in Unbreakable.) The council of elders appears to consist of twelve members, of which only eight have speaking parts in the film. Here are the two shots that introduce them, during the first council meeting:

The first town hall meeting, where the villagers discuss yet another unsettling discovery of a skinned animal, is shot in one take, the camera slowly closing in. At the start, eight members of the council are fully shown, and the camera will end up resting on four members:

This slide show reveals some kind of game going on in the background, while the pair of Edward and Kitty discuss her feelings for Lucius. (1) First two people pass, (2) then three more, (3) but a fourth one comes running, (4) joins them, and (5) then two more figures pass:

There are, of course, scenes that break with this “binary” pattern. But it is interesting that some key situations with three characters signal dysfunction. The main characters Ivy, Lucius and Noah are gathered, for the only time in the film, in the Resting Rock scene, and Noah will eventually turn against both the others. In the below scenes, Edward suggests breaking the taboo of contacting the outer world, to the others’ great consternation, and most dysfunctional of all are the three people who are supposed to go to the towns for medicine, where both of the cowardly men will very soon return to the village.

The second quiet room scene includes Noah’s father as a third person, and the situation will turn very violent. Are there any other scenes with three characters? The Percys discover the bloodied Noah on the porch, but they never simultaneously appear in the shot. The same goes for the scene where Ivy stands in the door during the invasion, with Kitty and Noah in the cellar trapdoor urging her to come in.

A final note about harmony: one reason for the particularly eerie atmosphere of the three (!) shots depicting villagers “sleepwalking” as they discover the livestock massacre, is that virtually everyone is suddenly moving one by one, placed in clearly defined layers into the shot’s depth dimension (just have a look here). This “every villager an island” behaviour completely breaks with most of the film, as we have seen. The contrast is made all the more haunting in light of the scene just before, where the villagers are carefully shown walking in a file towards the village centre, almost everyone, except Lucius the loner, walking in pairs.

Walls

Another pervasive motif is scenes that are flanked, almost always to the left, by a wall, fence or other obstruction. The shots may seem exceedingly harmonious, but the presence of the wall is constantly unbalancing the idyllic composition, nicely invoking the very artificiality of the village’s existence:

Another possible purpose is that these objects serve as a manifestation, as a constant undercurrent or foreshadowing, of the high wall that forms the perimeter of the animal preserve:

Sometimes this type of composition provides subtle connective material when cutting to the next scene: below, the interior wall improbably turns into the border fence (Lucius is unable to reach the mind of his mother, who has retreated into the other room; neither is he supposed to reach what is inside the woods – it is also notable that she disappeared out of the shot in the same direction he will take into the forest):

The following slide-show lists occurrences in chronological order (except for collecting the unusual type of right-side barriers at the end)…

…we end with this major scene, barrier on the right, in which Edward’s wife tries to persuade him from going to the towns.

Other motifs

There are also some motifs of a more minor type. The houses sure look nice but are not depicted with the visual significance bestowed by distorting lenses in Signs. Objects are sometimes lingered on, however, as if to assign them special meaning: the ring on the cellar trapdoor twirling with the impact after Lucius and Ivy have escaped down it during the invasion, and the padlock on the quiet room door swinging when the imprisoned Noah hammers on the door.

The very subtle, but extensive and ingenious motif of wind/breathing will be explored in the third article as it is tightly bound to the murder sequence. But there is a relatively large motif of characters shown in frontal/profile positions. It was already evident with Lucius and Ivy in the colour chapter (here) and a variation occurs in connection with the door motif (here), where characters are methodically shown coming in from left and right, and then frontally. The major part of this motif seems reserved for the yellow cloaks, and the visual artifice of the motif excellently suits the highly ritualised usage of the cloaks. (The appearances of the red creature during Ivy’s quest through Covington Woods also fit into this scheme, as we shall see in the third article.)

Ending The Village: convergence

After having examined some of the tools to read the film, we shall now walk through the film’s ending. In addition to interpreting events, there is a special emphasis on how it interacts with the rest of the film – for example, as regards motifs, alliteration, plot and theme – and how the awareness of this can create fresh meanings and metaphors. (“Flashback” screen shots are marked with red borders.)

There are more allusions to lifting in the film: the secret box, containing the data about his father’s murder, is Edward’s burden and something intensely personal. Ivy’s predicament was described by Edward thus: “You gave your heart to this boy. He is in need. Are you ready to take this burden, which, by right, is yours and yours alone?”

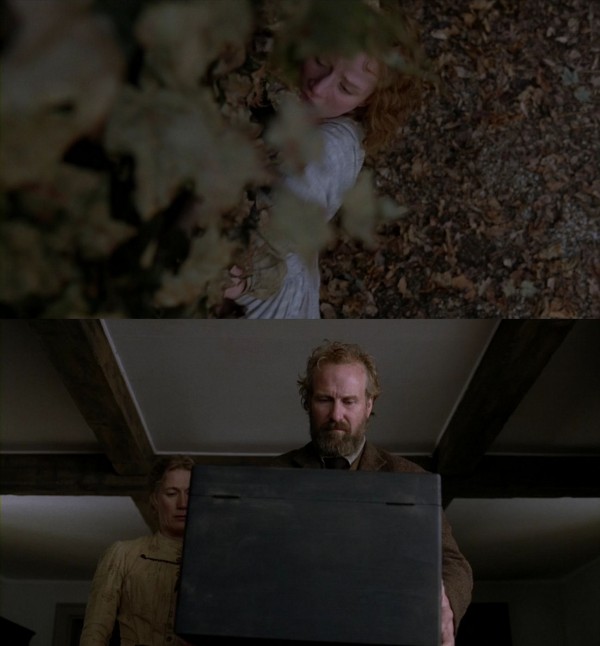

Edward and Ivy’s walk towards “the old shed that is not to be used”, with its almost ritualistic three stops, ended with withholding the scene’s climax, the unlocking of the shed door. Later we learned its secret, that the creatures were a hoax staged by the elders. Now another layer of secrecy is about to be peeled off, again by unlocking. The musical theme from the shed scene is repeated, and the film is fetishising the opening of the box by lingering on the turn of the key, transforming it into a ritual, and then almost imperceptibly closing in on the key:

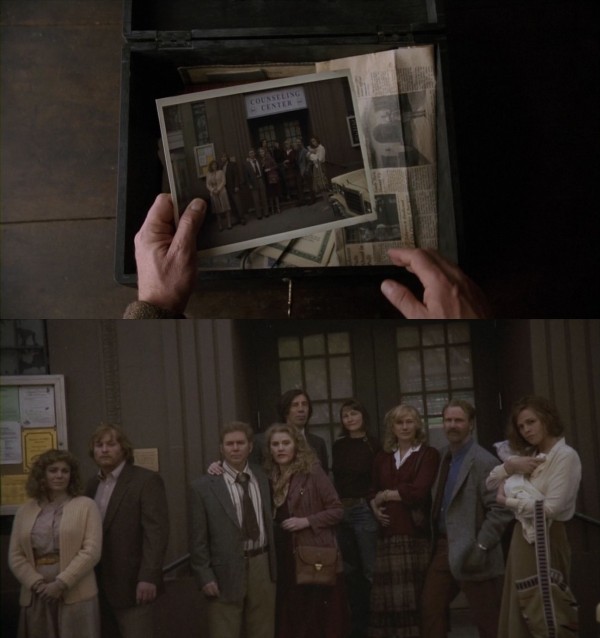

Over the opening of the box we hear four “death stories” (for complete texts, see addendum C), terrible compressed tales of the elders’ loved ones done in by violence, recited in piercingly dry and terse voices. We gradually realise that what we hear is long ago presentations at the counseling center in the photo. Edward ends the last one with: “I am a professor. I teach American History at the University of Pennsylvania. I have an idea that I would like to talk to you about.” (Although far from harmonious, it is tempting to connect the number of stories to the motif of pairs and fours and so on.)

Ending The Village: a meeting of innocents

Mrs. Clack’s death story utilised the word “dumpster”, then we saw the photograph, the clothes the people wore, and not least the car (but only a small part of it was shown, teasingly) – a gradual awakening to the fact that something is amiss with time. It could have been time travel, but a sudden cut to a new scene, from inside a car, with a siren wailing as Ivy is lowering herself down from a wall, drives home for the first-time viewer the hard reality that The Village all along has been set in the modern world.

There is some more sly editing at work here, however:

The Walkers are looking down, at the photo – a suddenly introduced framing depicting the modern world, which is exactly what we get in the next shot (even with an added, implied framing from the car window). The Walkers are looking at modernity, into which Ivy is about to step. They are looking, the driver is looking, at a girl who cannot see.

After the high drama of the quest, culminating in Noah’s death, this scene seems prosaic and anti-climactic. But its quietude, warmth and simplicity have grown on this author, who now regards it with great fondness. As the only scene in The Village, and virtually the first one of the pentalogy since The Sixth Sense, it is based almost in its entirety on an extensive shot/reverse shot construction of the most traditional sort (with a completely static camera, setting it aside from the somewhat similar “death story” scene between Alice and Lucius). This decision seems to emphasise the ordinariness of the situation and a world suddenly drained of magic and mystery. Dialogue also returns: except for some brief lines in the scene where the Percys discover Noah’s escape from the quiet room, there have been only two lines of dialogue for the last 14 and a half minute.

What other emotional undercurrents might be produced by this sudden “normalisation” of the film’s formal language? It underlines the fact that Ivy and the guard, Kevin (Lupinski according to his uniform tag), are of different realms, since they never share a shot – except for Kevin’s arm in the “under-the-shoulder” set-up used for the Ivy shots. Eschewing the standard “over-the-shoulder” lends a little strangeness after all. The scene shifts into closer shots when Kevin takes one step forward to take Ivy’s “prescription”, and the framing climbs higher up on his shoulder. The increased proximity and more normal “almost-OTS” set-up signal a new stage in their relationship, for it is at that point he understands she is blind and someone is hurt. The inclusion of Kevin’s arm seems to fix the scene from his viewpoint, struck by this sudden apparition from the wilderness. This shift also creates some balance since our sympathies clearly are with Ivy in the first place. Furthermore, there is a marked similarity in composition to the scene where Ivy’s sister Kitty declares her love for Lucius, making Ivy’s humility even starker in comparison with Kitty’s naive exuberance (Kevin even bears some resemblance to Lucius, and his initials K. L. are quite close):

During their conversation Kevin grows increasingly incredulous as he realises that Ivy lives inside what he knows as the Walker Wildlife Preserve (a well-chosen name, what is preserved is 19th-century life). Finally he agrees to fetch the medicine she is craving. Curiously enough, considering the supposed depravity of the outside world, the baby-faced Kevin (perfectly modulated by Charlie Hofheimer) comes across as equally innocent, maybe even more, than the villagers. (Kevin’s exaggerated swagger to signal authority when he comes towards her is very sweet – and wasted on the blind girl.) He holds up well compared to Ivy, the original innocent, who has become less so through fighting the creature, killing it. Why does he really agree to help her? It might be a manifestation of what Edward says about Ivy during the elders’ crisis meeting: “…she is led by love. The world moves for love. It kneels before it in awe.” Like Edward in the meeting, Kevin will now risk everything for innocence.

The scene’s apparent simplicity is deceptive, with many well-hidden points. In a film dominated by the “magical colours” red and yellow, Kevin’s car is all-green and his uniform all beige/brown. Kevin’s uniform is his “safe colour”, bestowing authority and protecting him. The green car is his “creature”, and it seems highly significant that it sounds a piercing siren when Ivy appears, in a parallel to the wailing of the creatures. The motor is running throughout the scene, its purr echoing the creature’s low growling. Technology is central to the modern world, so the car also embodies the threat from which the villagers have fled. It is a constant presence: in every shot of Kevin, we see the car over/near his shoulder. His one-coloured uniform also nicely connects to Ivy’s ability to “see” other people’s colour – it is tempting to give this some metaphorical importance in their brief meeting of minds.

There are other whispered echoes: when Kevin calls in the news of having discovering the girl on the radio, he says he is at “Mile 27”. This use of numbering to pinpoint locations resembles Ivy’s method of counting steps to keep her bearings in the village (we hear her counting under her breath on the way to Lucius’s house where he lies injured). In adherence to the wall motif, we always see the receding wall of the preserve in every shot of the scene (except the close shot fixating on the car door).

In great contrast to the film’s feverish yellows and reds, the colours of Kevin and the car are drab, in line with the paleness of the minuscule piece of the modern world we are allowed to glimpse. Ivy too has lost her colours, the yellow cloak discarded just before, leaving her with a pale dress. On a metaphorical level too: her sudden humility is striking – it is remarkable that this vulnerable, hesitant girl is the same we have seen inside the walls, burning with vitality, bossing others around. The girl who has just killed a monster is now unable to cope, helplessly depending on a complete stranger, defenseless against the enormity of the outer world. Her charisma brutally stripped away, it is almost as if her village persona was only a daydream in the mind of a girl of the modern world.

On the other hand, it is her innocence that enables her to convince Kevin, that makes her able to say: “You have kindness in your voice. I did not expect that,” in such an utterly disarming manner – the first line that starts to sway him. The irony is hilarious when Kevin later asks her: “You’re not tricking me, are you?” and she has no idea what he means (“trick” seems beyond her 19th-century vocabulary). The master trickster, who cheats on Noah to get a head start in the race to the Resting Rock, and makes Noah-as-creature fall to his death in the pit, does not know what Kevin means!

There is also a very nice progression: the film names her for the first time when Noah says: “Ivy, you cheated!” (how apt!). Then Lucius says just before his declaration of love: “That is why I am on this porch, Ivy Walker. I fear for your safety before all others.” (Lucius is also using her surname in his second petition to the elders.) Here, when Kevin finally asks her name, we hear it in full for the first time: “Ivy. Ivy Elizabeth Walker.” But her tone initially rises, as if she is now questioning her whole identity. (Hearing that Ivy is named Walker, the name of the preserve, may well have solidified Kevin’s willingness to help.)

The softly serene music – called “Will You Help Me” on the official soundtrack – contributes an enormous, yet hardly perceived heightening of the scene: like in many other The Village scenes, the music sneaks in only after a while, as if first allowing the situation to be seen in a purely realistic light, then lifting it up to metaphoric, universal level. The music is timed to start on the word “woods” in the exchange: “Where are you from?”; “The woods”. When he asks: “Is someone hurt?” there is new development, Hilary Hahn‘s violin joined by harp and flute, in a pleading tone. Soon there is a flourish as she realises he can get the medicine, and then another, with great warmth, when she gives him the watch as payment.

Ending The Village: the guard shack

The music is cut off by the next scene, substituted with a radio announcing murder and war – the soundtrack of the outside world. (Shyamalan’s next film Lady in the Water employed the Iraq war as a consistent backdrop.) The character of Jay, the head guard, may seem like a foreign body in the film, but actually he easily fits into the general scheme. The connection is strikingly illustrated by juxtaposing the opening of this and the last scene:

Excuse the “flashforward”, but among the many scenes filmed inside a house towards an open door, this one provides the most striking visual parallel. There is another echo: we neither see the face of Jay (directly; he appears in a reflection) nor of Lucius in the last scene. There are many other similarities between Jay and the villagers: the prime directive of both is to “maintain and protect the border” (the border of the preserve; of the village). Like the villagers (and most people in the real world) Jay has created a safe existence in order to cope with a threatening outer world, represented by the disasters on the radio and in Jay’s newspaper. Furthermore, with all his good advice for Kevin, he is a mentor figure, like the elders of the village.

It is almost as if the newspaper – prominent at the start and end of the scene – is Jay’s shield, his border, against the world, and in his insulated existence the terrible news is just words to him, like his face only appears as a reflection in the medicine cabinet, not fully real. There is one big difference, though: Jay comes across as cold, lacking the harmony and warmth of the villagers. One shudders to contemplate what would have happened if he, rather than Kevin, had chanced upon Ivy. His surly, uncaring and slightly arrogant tone is a far cry from Kevin’s “kindness in your voice”. On the other hand: viewing the job as an “easy gig”, his complacency and lack of curiosity make him the ideal keeper, allowing the villagers to live undetected inside the preserve, but also letting Kevin steal the medicine from under his nose.

The scene in the guard shack has been criticised, and one can agree up to a certain point. The name “Walker” is plastered rather obviously in a great many places (on the car, on the caps and uniform, with one cap very visibly placed on the desk in the foreground as the scene starts). Shyamalan plays Jay himself, and in a way it is fitting that the creator of The Village is allowed to provide the expository dialogue – viewed by many as inelegant – sketching in background information about the preserve. Quite a lot of it is not that expository, though, since it is not unnatural to explain the lay of the land to an inexperienced guard like Kevin.

This author’s biggest complaint about the scene is its lack of mood and tension, thus arriving as a bit of a wet blanket in a film crawling with creativity and distinctiveness. It has none of the lyrical current and subtlety of the previous, similarly ordinary scene. There is another problem: we never see Jay’s face except when he appears as a reflection in the medicine cabinet. The main idea is probably to create suspense, because if he raises his eyes from the newspaper just one bit, Kevin will be in big trouble, not to speak of Ivy’s mission. But it falls flat – not even a glimmer of tension has ever been felt by this viewer, a rare misfire for a director who normally operates suspense with surgical precision.

This situation connects to an earlier moment, however. Like most filmmakers Shyamalan loves reflective surfaces. (For example, see the reflections in the TV screen in Signs.) But in the village there is not one mirror – perhaps one of its rules? – however we find an incredibly complex shot where a person passing by casts a labyrinthine number of reflections in some medicine bottles (see above, her dress can be seen in the central bottle) concluding the scene of the discussion on how to “mend” Lucius. The two images are connected through reflections, a person being reflected, in a shot to do with medicine.

Ending The Village: leaving innocence

After Kevin leaves the shack, we get an intermezzo consisting of four shots, accompanied by a poetic rendering of the main musical theme. It seems like utter simplicity, but again an enormous amount of things are going on. First comes a shot where the camera tilts upwards looking up into the trees. The weather is completely still, in great contrast to how the wind shook and bent the trees when Ivy fled the creature. The wind reflected her panic and heavy breathing – a remnant was still tousling her hair when she met Kevin – but crisis has now been replaced by serenity:

Then there is another reflection. Like the one in the shack this too recalls an earlier shot. Ivy is walking by the stream, echoing the eerie red apparition that ends the montage of the post-funeral activities early in the film. Shots of reflections that reflect each other, yellow having conquered red:

The third shot is from a high vantage point, as if the forest as a collective entity is gazing down at her. The camera is calmly sliding downwards along a thick trunk. Ivy is seen as one with the forest and we recall how it helped her when the tree root “shook hands” with her, reminding her that she was near the pit. (We will look further into her entire quest and to which degree she becomes one with the woods in the third article.) Like by the stream, she appears as an ephemeral figure, almost indistinguishable from the environment:

Not only is Ivy’s minuscule figure already dwarfed by the forest, but she appears from behind a tree (the third one from the right in the foreground) and at the end disappears behind another. She is literally swallowed up by the woods, by its foremost representative: the broadest trunk, which dominates the shot. (This is the only shot in the film with snow on the ground – shooting finished in December.)

The following slide show gives an impression of the editing and flow of the last two shots of the intermezzo (the frame grab with yellow borders marks the first one):

Let us break the last shot into single moments and see what can be found:

One fine day, Kevin Lupinski experiences a miracle, a blind and dirty girl in an old-fashioned dress coming out of nowhere, only to be disappearing into the unknown again. Now the ephemeral earlier shots get a different meaning: Ivy is flowing away with the stream, swallowed up by the forest, becomes one with the woods – to Kevin it is as if she never existed or was just an apparition. The handover of the medicine is judiciously left out of the film, adding to its understated air and Kevin’s feeling of unreality. Using a timepiece as payment is fitting for a transaction that has crossed from one era to another. Now looking at the memento of the watch, Kevin is a modern man gazing back at the past, like the viewers of The Village have been doing for most of the film, pondering the story of Ivy.

The shot gives an impression of someone left behind. The editing constructs a continuous downward movement from high up among the trees down to the road level, linking them, but Ivy was moving and Kevin is stationary. The car door is open, like so many other doors in the film, and the warning signal sounding from the car is a sound of yearning, like a sad echo of the vigorous siren that hailed Ivy’s appearance – as if not only Kevin, but the car as well is lamenting the situation. Thus Kevin’s involvement in The Village both starts and ends with meaningful sounds.

As mentioned, the car represents a central element of the era the villagers have forsworn: technology, and it also recalls the forest creatures. Now Kevin sits trapped in that beast, the modernity that controls him. But the open door suggests a means of escape. The ladder – very close to the door! – pointing into the air is even more suggestive: it could easily be leaned against the wall of the preserve instead. Kevin is the only human being of the outside world with an inkling about the goings-on inside, and it is a fascinating thought that Kevin might join the village at some point. But since he stands for hope, trust and innocence, he could also be a force in the outside world.

Here is something that is at least an amusing coincidence:

Finally, our farewell to Kevin flows nicely into the film’s last shot. The centrality in the shot of the car fits the door of the infirmary, and there are open doors in both shots, even two in the last one, with the schoolhouse door in the background:

Ending The Village: the final shot

The Village ends with a 154-second shot, collecting all the major players inside the infirmary. It suffers from some of the same problems as Signs, where the last two scenes did not achieve their intended resonance (further detail here). Perhaps Shyamalan tries to pack too much into one situation. The vote among the elders to continue the village after the news of Noah’s death is supposed to be a very emotional situation, but it comes across as rather mechanical, as if the characters suddenly are puppets moved around. The same goes for the inorganic way that the Percy couple have to take the news, however much prepared-for, of Noah’s death virtually in their stride, as a plot point without real emotional impact. The latter item could be said, however, to be part of a certain stylisation and theatricality of the film (particularly with the elders). After all, upon hearing for the first time how his father died, Lucius reacts with some shock, but after protesting “Why’d you tell me this blackness?” the scene goes on unspooling. The Lucius scene, however, did not strive for the last scene’s sense of finality and poignancy. But as soon as Ivy enters, her glow instantly restores the film’s resonance.

As usual in Shyamalan, there is no lack of ideas in mise-en-scène and interconnectivity. Below, the eight “speaking part” elders are grouped in four pairs, in accordance to a familiar motif, both by being pairs and the number four. From the left: The Percys (due to being a married couple and proximity), Alice and Mrs. Clack (colour of clothes), Victor the doctor and August (colour of clothes, position by the door), the Walkers (married couple, proximity). The diagonal placements of the married couples mirror each other.

In the photograph from the Walkers’ secret box, there are five pairs. From the left: August and wife (she must have died in the village after bearing Daniel), the Percys, Victor and Mrs. Clack, the Walkers, Alice and her baby. The infant must be Lucius (which means the village is roughly as old as him – 25?). These “earliest” and last chronological situations in the story of the village have myriad parallels. A door is central in both shots. In both situations, Alice’s head is bent over her son. Major decisions will be made: around the time of the photo they will decide to found the village, in the last shot they decide to go on with it. The decisions come as a response to acts of violence: the death of their loved ones, and Noah’s attack on Lucius and his own death.

Edward says that Noah “has made our stories real,” meaning that his death will have served a purpose, by solidifying village lore through the lie that he was killed by the creatures. Originally, the screenplay also provided a more concrete meaning: in a deleted scene on the DVD, August tells a fake story about how his brother was killed by creatures in the woods. Ironically, Noah has also managed to turn red into a true “bad colour”, spattered with Lucius’s blood when discovered by his parents on the porch.

As a conclusion to the action of the last shot, Ivy will enter and highly explicitly form the fifth and “missing” pair (compared to the photo) with Lucius, representing the future of the village. This also concludes a lot of connective material between the two, see here and in the second article. In multiple nice touches, both the baby and adult Lucius are in white, helpless and with hidden faces. It is also fitting that he is “a child of the village” in the photo, a uniqueness that fits with his eccentricity and loner status in the community – does the fact that he was born outside the village exert some mystical pull, drawing him back to the outer world?

When Ivy turns up we will see a long chain of handiwork. Ivy is of course blind and needs guidance, but the others could just as easily have grabbed her arms and body, so the mise-en-scène seems specifically tailored to creating a pattern:

In addition to all the echoes between the last shot and the photo, there are also connections between another set of chronological extremities, the film’s last and first moments (by the way, note the continued presence of hands via Mrs. Clack’s hands on the bedpost):

Burial has already been alluded to via Edward’s statement about Noah: “We will find him. We will give him a proper burial.” In the last second of the film, we see August in the background by door, in the same clothes as during the burial. Then he looked death in the eye, here it is life. More resonance is provided by Lucius being a kind of substitute son to August, as he himself once said to Lucius: “I often wondered if you and my son bonded because neither of you is fond of speaking.” But also in the ending there are someone who have just lost a son, namely the Percys. Both the first and last shots contain spectators, in the ending a further layer through the villagers on the square. Behind them we see a tree and a house, representatives of the forest and the village, the two most powerful forces of the film. There are streaks of tears from both of Ivy’s eyes, concluding her frequent crying in the film.

From the exact point where Ivy takes over from Lucius as the story’s main protagonist after the murder attempt, (except for one scene) we never see Lucius’s face. So here in the last shot we again experience him like the blind Ivy does, feeling his presence through other senses. The last non-musical sound of the film is Lucius’s laboured breathing. It has a peculiar ring to it, sounding almost like the wind. The interchangeability of wind and breathing will be discussed as a subtle yet important device when analysing the murder and quest sequences in the third article, and Lucius’s wind/breathing in the infirmary forms a connection to the windy conditions in the first shot. Then we had wind during a burial, which is highly suitable since in the murder scene wind is heavily connected to death. In the last shot there is a big difference, however: in the murder scene, the wind was Lucius’s life blowing away, but here his breathing-sounding-like-the-wind means he gets his life back.

Finally, as the third article will fully chart, The Village is a film that takes great care in giving poignancy to its characters’ last words. In fact, one could argue this already starts in the opening scene, with August’s poem-like farewell to his dead son.

In the Kevin scene the next-to-last thing Ivy says in the film is “Ivy. Ivy Elizabeth Walker.” In its dying seconds she now says “I’m back, Lucius.” The names of the probable future leaders of the village are wrapping up the film.

*

Addendum A: The ambiguity of the final situation

The last scene is laden with finality, but the final situation of The Village is ambiguous on many levels. How much has Ivy understood about the outside world? Kevin speaks of “guard shacks” and “preserve”, and she asks about the cause of the siren noise but we never hear an answer. There is no indication that Ivy realises that the outside exists in another century. Does she know that Noah played the creature? The little flourish ending the first Lucius/Ivy porch scene, where she does not notice Noah hiding in the closet, seems specifically designed to demonstrate that, unlike with Lucius and her father, she cannot “see his colour”. Her behaviour during the struggle consistently indicates that she thinks it is a real creature. It is strange, though, that her heightened sense of hearing did not pick up the dying Noah’s whimpering down in the pit, but this is explainable with the stress of the situation. Although inadmissible as evidence since not part of the film, the most interesting of the four deleted scenes on the DVD shows Ivy, just after Noah’s death, reaching a contraption hanging in a tree that uses the wind to produce the howling of the creatures. She seems to think real creatures make the sounds, and pleads for safe passage (because, as she so movingly shouts, “it is for love that I am here”).

There are many layers of irony here, connected to her lack of sight. She now believes there are monsters in the woods after all and does not understand there is a modern world out there. Will Ivy go on believing in the creatures? It strains credulity that an intelligent person like Ivy would not see through the elders’ new story that creatures killed Noah. It will be too much of a coincidence, supposedly happening at the same time as the drama by the pit. But at one point, Ivy will have to know the truth, for how else shall the next generation maintain the illusion of the creatures? Will Edward ever tell Ivy about the reality of the outside world? How much does Edward himself know about the precise state of that world after 25 years? An interesting side effect of Ivy’s quest is that the medicine can also be used for others, improving the mortality rate of the village. Will they be tempted to make further contact with the outside?

The ending is also very ambiguous morally, to say the least. For example, what about the other elders who were not part of the vote? The inner core decided to go on with the village even though it turned out that violence can occur there too. The massive deception towards the younger generations will continue. But how could they return to the real world? The village has existed for 25 years and the non-elders (especially) will suffer massive culture shock, not to speak of the blow of realising that their parents have been forcing them to live an illusion. At the same time, the elders are unquestionably portrayed as benign and warmhearted, and the villagers seem basically happy. Maybe illusion is best after all?

Addendum B: the time period and other practical questions about the village

The gravestone that appears in the third shot of the film declares the year as 1897. Michael Bamberger has written an excellent, nuanced Lady in the Water making-of-book, “The Man Who Heard Voices: Or, How M. Night Shyamalan Risked His Career on a Fairy Tale” (New York: Gotham 2006). He reports that Nina Jacobson, then-president of Disney whose formerly great relationship to Shyamalan was gradually souring, opined that showing this year was to cheat on the audience. This sort of criticism was one of many reasons that Shyamalan left Disney after The Village. He was aghast at the superficiality of the remark – rightly so.

Besides being a useful indicator to the audience as to the specificity of the time period the villagers are supposed to inhabit, all the non-elder villagers believe the date to be 1897. Judging from the age of the second generation (Ivy, Lucius, Noah), and the pre-village photo from Edward’s secret box of Lucius as a baby, the elders withdrew from the world some 25 years earlier. The radio newscast and newspaper in the guard shack scene seem to place the real time of the outside world in 2004, judging from the mentioning of something sounding like the Iraq War and the year in the date on the newspaper. This means that the elders withdrew from the world in about 1980, and adopted the life style and knowledge of about 1870.

Since we see books around – and one of the deleted scenes indicates there is a library on the second floor of the town hall, where August can also be seen reading in one of the film’s post-credits photographs – the village is founded on a basis of written knowledge. Then it follows that it needs a way of marking time passed since the establishment the village, which fits with that basis and the years mentioned in it. Showing a gravestone with 1897 is then perfectly consistent with village life and not cheating.

As an aside: props are often a big consistency headache in films. The date on the above-mentioned newspaper is not entirely trustworthy: it contains the continuity error of giving July as the month even the current action clearly takes place in late autumn. An even wetter blanket is the fact that the gravestone too is inconsistent. If one magnifies part of the second shot showing the stone from another angle, it is clear that the inscription not only is different in a number of ways, but it also gives the birth of the boy as 1889 not 1890. (I originally magnified it to try to determine the month of his death, to pinpoint the time of year the film starts, but it cannot be trusted. I would go for October though, and the later part of the action taking place in late November – there is a clear time ellipsis in the film at the point of Kitty’s wedding, when the foliage of trees has suddenly gone.)

The elders also needed to establish a way of speaking that would tally with the books existing in 1870. Being people from modern times, however, they speak it imperfectly, leading after 25 years to the not-quite-late-19th-century lingo we hear. Shyamalan has written the dialogue to reflect this fact, also as a harbinger of the twist, since even non-language-experts in the audience will feel something to be slightly askew. For example, contractions are normally not used, but is present in so central a term as “Those We Don’t Speak Of”. (By the way, for a taboo subject the creatures are spoken about an awful lot in the film!)

The language angle also leads to some sly humour. One of the first things Edward says in the film is: “What manner of spectacle has attracted your attention so splendidly? I ought to carry it in my pocket to help me teach.” The florid, convoluted, faux-elegant statement, uttered in one fast breath, is amusing in itself, but also in contrast with the prolonged silence as he spots what the children are so fascinated about: a skinned, bloodied animal. (This points forward to the “crazy lady” of The Happening (2008) speaking a parody of syntactically tangled, rural folksiness, like “Ain’t no time two people staring at each other, or standing still loving both with their eyes are equal.”)

Otherwise, it must be said that the basic premise of The Village is so unrealistic that it is clearly to taken as a fable or metaphor. It does that magnificently, but let us for a moment indulge in some of the difficulties. Unless there is an area we are never shown, there are way too few houses to support the considerable number of people we see during gatherings. And how could there be so many younger people, given that many of the (only 12 in all?) elders seem to be childless, have only one child, or have children with no offspring? In such a tight community, how can the elders sneak away so easily (for 25 years) to play the creatures? How did all the elders manage to disappear without a trace from the outer world? How could the village be built in secret? (If the small number of elders did it themselves, it must have taken a long time.) If the village existed from before, how could the elders acquire it in utter secrecy?

Addendum C: The death stories

The Village contains four “death stories”– for they are compact stories, rehearsed and honed to perfection over 25 years – apparently told by the elders at regular intervals to the younger generations to keep them from leaving the village. One also has the feeling they serve as self-hypnosis, ensuring that the elders will continue their Utopian project. They are told, in uncensored versions, by voice-over when Edward is opening his family’s secret box close to the end of the film.

- Mrs. Clack: My sister did not live past her 23rd birthday. A group of men raped and killed her. They stuffed her in a Dumpster three blocks from our apartment. (Earlier version, told to Ivy during the wedding: My sister did not live past her 23rd birthday. A group of men took her life in an alley by our home.)

- August Nicholson: My brother worked in an emergency room downtown. A drug addict came in with a wound to his ribs. My brother tried to dress the wound. He pulled a gun from his jacket, then he shot my brother through his left eye. (For what it is worth, in a deleted scene August tells Lucius and Noah a dramatic story of how his brother was killed by the creatures.)

- Alice Hunt: My husband, Michael, left for the supermarket at a quarter past nine in the morning. He was found with no money and no clothes in the East River, three days later. (Earlier version, told to Lucius: Your father left for the market on a Tuesday, at a quarter past nine in the morning. He was found robbed and naked in the filthy river, two [sic] days later.)

- Edward Walker: My father was shot by a business partner, who then hanged himself in my father’s closet. They had argued over money. (Earlier version, told to Ivy on the approach to “the old shed that is not to be used”: Your grandfather, James Walker, died in his sleep. A man put a gun to his head and shot him while he dreamed.)