Signs, Part III: Dreams, demons and birds

This article is part of an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006: The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Signs (2002), The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006). This is the third article about Signs. The first is here, the second here, the fourth here. The articles about the other films can be found in this overview.

This article shall first explore some important subtexts: dreams and magic and the aliens as representations of humankind’s inner demons. It will then round up references to The Birds, an inspirational work for Signs. The article concludes with exploring two motifs and two late segments of the film where they become crucial: the flashlight motif in preparation for analysing the cellar sequence, and the use of windows to better understand the film’s ending. There is an addendum detailing references from Signs to other Shyamalan films.

*

In order to discuss the film properly, I will have to reveal the whole plot, including the plot twist at the end.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of Signs, here is a brief outline of the plot.

Signs of dreams

Did I ever tell you what everyone said when you were born, Bo? You came out of your mama, and you didn’t even cry. You just opened your eyes, and you looked around the room at everybody. Your eyes were so big and gorgeous. All the ladies in the room just gasped. I mean, they literally gasped. And they go, “Oh, she’s like an angel.” And they said, “We’ve never seen a baby so beautiful. And then… you know what happened? They put you on the table to clean you up, and you looked up at me and you smiled. They say babies that young can’t smile. You smiled.

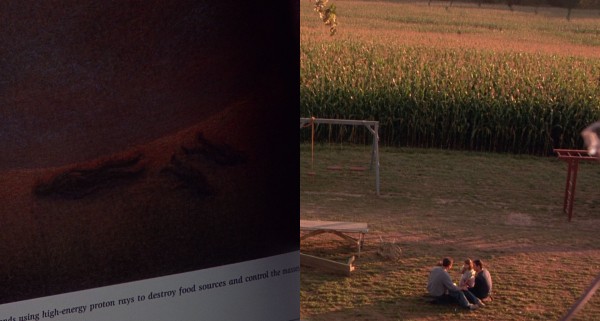

Signs seems intended as a fable – the aliens could be sent by God to test humankind or they simply represent our inner demons – and should not be held to standards of realism. But there is another reason that real-world logic and plot consistency may not be that pertinent. Throughout the proceedings there is an undertone of the surreal, of something slightly out of whack. Nowhere is this as pronounced as in the disjointed and abrupt opening sequence. But other than that, how to account for the fact that Morgan’s book on extraterrestrials seems able to predict virtually every step and explain the nature and motivation of the aliens? Also, there is the deliciously eerie scene showing that the book has a drawing of a house very similar to the Hess residence, with three dead bodies outside (corresponding to Graham and the children who are reading the book at this time). Consider also the silliness of the tinfoil hats that are supposed to prevent the aliens from reading their minds.

On some level, it is tempting to treat the film as a dream – perhaps not literally, and certainly not to “explain away” plot problems, but at least as a prism to watch it through. Film convention has already established that if a story at the end turns out to have been a dream, this is accepted even though it has not behaved in a totally unhinged way, like real dreams do (which would of course too clearly have signalled it to be a dream). I propose that what we see in Signs could be a nightmare from a little girl’s perspective. This point-of-view is literally the case, by the way, when Bo rushes towards the window in the film’s climax to watch Merrill battle the alien, and we look over her shoulder:

The film also overtly connects Bo to dreams, which can even foretell the future. Morgan takes this seriously (he calls her clairvoyance a “feeling”). She has dreamed that her brother will die in an alien attack, and we are shown that only divine intervention prevents this from happening. In the prologue, she is supposed to be half-sleepwalking and when Graham reaches her, she asks, “Are you in my dream, too?” (This is one of the film’s first lines, lending it extra emphasis.) He answers, “This is not a dr…” but is interrupted by Morgan shouting. So that Signs is a dream is never properly denied. Even though perfectly fitting for a horror film, this also accounts for the nightmarish nature of Graham’s various encounters with aliens and the “horror show” of the Brazilian videotape. Through this prism of watching Signs, the aliens’ sometimes “silly” look, the childish way they can be defeated, and precisely through Bo’s own quirky relationship to water – all this fall into place. In fact, the abundance of silly humour in the film also fits into a dream perspective.

The dream aspect is also strengthened by other remarks. At one point Graham says, “Is this really happening?” and when he recounts the story of Morgan’s birth he says, “I wanted your mama to see you first, because she had dreamed about you her whole life.” Graham’s monologue about Bo’s own birth constantly emphasises how special she is, and even compares her with an angel. This is not the only thing that connects Bo with the supernatural. When we first see her in the distance in the prologue, she is walking along, eerily stooped, clad in white – as if a ghost. The fluffy chiffon material she is wearing as part of her apron dress for most of the film also makes her look kind of ethereal.

She is also connected to the shapes of stars and half-moons, which are traditionally associated with magic and wizards. In the family backyard there is a small playhouse whose roof is pierced by such symbols, shown from various angles in the top row of the below montage. When attacked by the dog she takes refuge in this structure, thus connecting her to it. The same symbols later serve as omens of danger, as the camera glides past this playhouse, emphatically showing off the symbols, when Graham goes to feed the surviving dog – the prelude to one of film’s most unsettling scenes, where Graham stumbles upon an alien in the cornfield. (Some swirling blue smoke gives that scene a light touch of dream.)

She is also connected to the shapes of stars and half-moons, which are traditionally associated with magic and wizards. In the family backyard there is a small playhouse whose roof is pierced by such symbols, shown from various angles in the top row of the below montage. When attacked by the dog she takes refuge in this structure, thus connecting her to it. The same symbols later serve as omens of danger, as the camera glides past this playhouse, emphatically showing off the symbols, when Graham goes to feed the surviving dog – the prelude to one of film’s most unsettling scenes, where Graham stumbles upon an alien in the cornfield. (Some swirling blue smoke gives that scene a light touch of dream.)

Bo seeking refuge in the playhouse prefigures how the family will barricade themselves in the real house before the aliens attack. Thus it is thematically fitting, and a brilliant visual idea, that part of the playhouse roof is used for the boarding-up (of a window, the other half blocks the fireplace – we can glimpse it behind Graham during the dinner quarrel scene). When the alien threat seems to be over, Merrill leaves the cellar to investigate. The shot (above) fetishises the “magic pattern” in manifold ways: its long (57-second) duration; its static gaze; it being “empty” for a considerable time as Merrill leaves the frame to check out the house; finally, the otherworldly sunlight the pattern lets in, all the more dazzling after the long time the family have spent in the cellar. (Sun, moons and stars mean that the three most prominent heavenly bodies are acting in concert – a nice touch.) The surprise of its appearance and its enchanting nature only add to the unreal feeling of the film. And, as in the scene with Graham and the dog, its appearance could yet again be said to herald danger: the lurking Nemesis Alien.

Awakenings are over-represented in the film, emphasising that the characters are sleeping and thus dreaming. Graham wakes up as many as four times (in the prologue; when awakened by Bo; after each of the first two flashbacks) and Merrill three (in the prologue; after having fallen asleep when he was supposed to guard the house; in the closet in front of the TV). Awakenings are also strongly foregrounded chronologically: Merrill and Graham wake up very early in the film, the latter as early as the second shot – and the stars on his bedclothes connect to the magic motif, and from there to Bo and dreams. Twice he wakes up after having dreamt, but as if Shyamalan intends to blur dream and reality, they are about the most calm and realistic scenes in the entire film. They are about Colleen’s traffic accident, and her death too is associated with sleep, as the sheriff tells Graham, “…we wanted you to come down here and be with her as long as she’s awake.” The third flashback to the accident comes when Graham is awake, in the form of a vision as he confronts the Nemesis Alien, shot in exactly the same fashion as the dreams.

The following elegant dissolve was dissected in the first article, but it also contributes to the dream aspect:

Here one of the many functions of the dissolve is to create an artificial nightfall. The first thing happening inside the house is that Graham is suddenly woken up by Bo. She claims to have seen a monster and soon Graham also sees it too (through a window, echoing the dissolve of the alien-connected circle of the mobile precisely into a window). Bo’s role as instigator and Graham’s awakening together hint that the alien may be part of some sort of collective dream.

The water motif provides another dreamy prism through which to watch Signs:

Inner demons

Like in Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), there is a strong sense that the external threat is a metaphor of the characters’ inner demons and existential angst. The aliens are almost never seen properly and even their spaceships are invisible, leading Merrill to point into an empty sky when indicating their presence. At one point Morgan says, “They know our secret thoughts” – ostensibly, because the family have forgotten their tinfoil hats in the hurry to hide in the basement – but the remark also doubles as a hint to the metaphorical nature of the aliens: they are the humans’ secret thoughts. This could account for the presence of several parallels between aliens and humans – like the water glasses above, but particularly between Graham and the Nemesis Alien, most clearly articulated in the pantry door scene.

The aliens are also connected to the four mobiles (as if one for each family member). At one point they start tingling as the aliens are disturbing them while tiptoeing around the house. In other scenes, the same tingling functions as discrete yet insistent signs of the characters’ fears. This is especially telling in a montage when the family are boarding up the house while waiting for the alien strike. The three mobiles of this montage and their sounds represent the anxiety of this very waiting, and the below slide show visualises how they virtually merge with Graham’s mind. The third mobile is shown as a reflection (to make it more immaterial?), before a dissolve – yet another meaningful use of this device involving a mobile – makes it seem to fuse with Graham’s head. This kicks off a 65-second fixed shot where the weird depth composition – with Graham in profile like so many times in this film – increases the strangeness of the scene. Here Graham displays signs that he may crack up at any time. He is clearly not expecting them to survive and plans a death-row-like last meal of their favourite dishes, before the shots ends with his almost diabolically stiff grin.

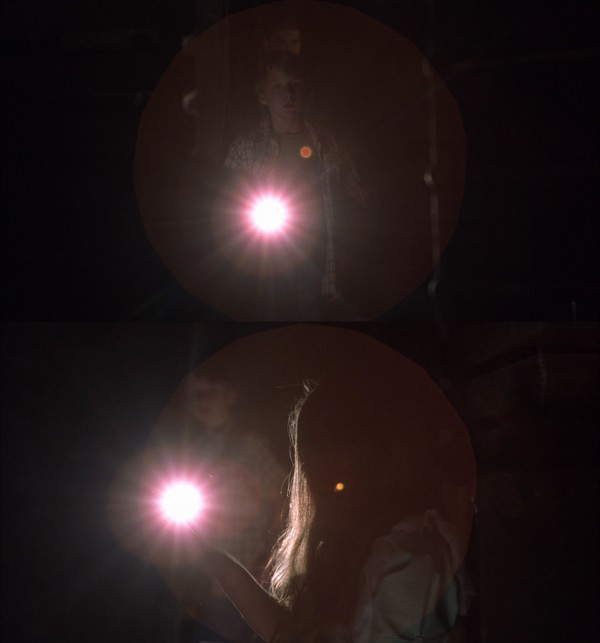

It has become a horror staple that the less one sees of the monsters the scarier they are, but this policy also fits the subtext of the aliens not being quite real. This might contribute to the fact that so many find it grating when we intermittently see the Nemesis Alien quite clearly during the climactic battle. But mostly we see it in hazy outline or as reflections. Shyamalan expertly uses the latter device during that scene:

The plaque reflection also creates yet another parallel between humans and aliens, but here it may be more specific: like the alien may be seen as an inner demon, the baseball bat does not only commemorate Merrill’s great triumph, but it is inextricably linked to his great failure as well – striking out badly as much as setting glorious home-run records. He now has a chance to exorcise this demon.

Shyamalan is adept at shaping (segments of) scenes so their start and end will reflect each other, but in non-conspicious ways. It is logical, then, that the dying moments of the alien is reflected in a TV screen, since it first appeared in the scene that way (see below). The reflections also continue a plan of visual thinking, because the last image on the TV before this scene was a test pattern, full of alien-connected circles, symbolising their attack. Unperturbed, Shyamalan maintains his pervasive staging-in-depth also in these reflection set-ups: in the uppermost shot we also see Graham “foregrounded” in the screen; the lowermost shot adds to the objects in front of the screen by showing the interior of the room:

The lowermost shot is particularly rich in meaning. Like the alien, lots of other items are overturned: the TV itself, the glasses and the video cassettes. The TV screen is cracked, like the highly important bedroom window to which we will return later. The boarded-up window in the far background reminds us of both the window motif and the siege. Distorted by the screen’s curvature, the red chair suddenly seems like an alien object and its arms are curiously echoing those of the alien. (Merrill fell asleep in that chair once – a dream reference?)

Throughout the film, a lot of the information about the aliens has been provided by TV newscasts, including the most striking item of all, the “horror show” from the Brazilian birthday party. This was the first time an alien was seen clearly, so it is “born” (as a fully enunciated threat) and dies on the TV screen. That first appearance was captured on video by the locals, and Morgan recorded on tape the historic news report that confirmed the aliens’ arrival. So the video cassettes strewn about here serve as some kind of memento over the aliens’ rise and fall. They are even reflected in the screen, “imprinted” on the alien body.

Furthermore, the alien’s TV “appearance” comments upon the old sci-fi movies to which Signs harks back, which are known to today’s audiences on a TV set (by station programming or DVD). In fact, the pervasive combination of TVs and aliens in Signs also promote the inner demon subtext, namely the idea of the film’s aliens as stories, created by humans as metaphors.

The science fiction genre was born in written form, so it is fitting, in a zany way, that the book on extraterrestrials should include this incredibly pulpy image, a nightmarish manifestation of Graham’s fears that he and his children will end up dead. It is as if they are projecting their predicament onto the book they are reading, which could be the “reason” for the similarity of the house with their own:

References to The Birds

Shyamalan has declared The Birds a major inspiration for Signs, and there are many references to or similarities with Hitchcock’s classic. The Bodega Bay provides an echo of the water motif. And after having gained familiarity with theme and atmosphere, the first thing that popped into this author’s mind upon the second viewing of Signs‘ opening shot, was a famous scene from The Birds:

There is a feeling that The Birds too is fetishising houses, with compositions placing them in elevated positions. (This is much more pronounced in Signs, however.)

There are three rapid, successively closer shots of the alien as it is shown to be injured by the water. This seems to be a homage to Hitchcock’s famous reveal of a bird victim:

As will be shown in the fourth article, one of the most important stylistic devices in Signs is its use of the depth dimension of the images. This is not as pronounced in The Birds – in many ways, Shyamalan will take various elements of his famous forerunner and magnify them – but the following slide show from a 125-second long take is a prime example:

The most important visual link between the two works is the use of flashlights. In The Birds it is used in the (in)famous scene where Melanie gets trapped in a room and is subjected to an extended bird attack.

During the attack the flashlight will add visual chaos to the scene, as the following slide show indicates:

Flashlight circles

In Signs flashlights also provides an extension to the circle motif.

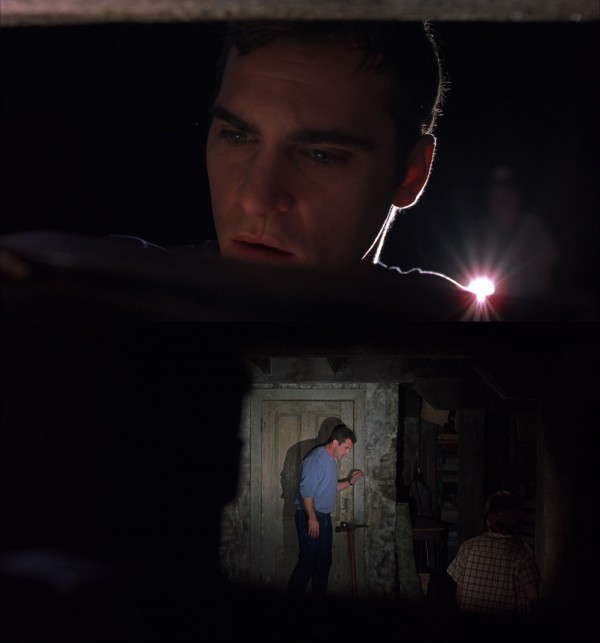

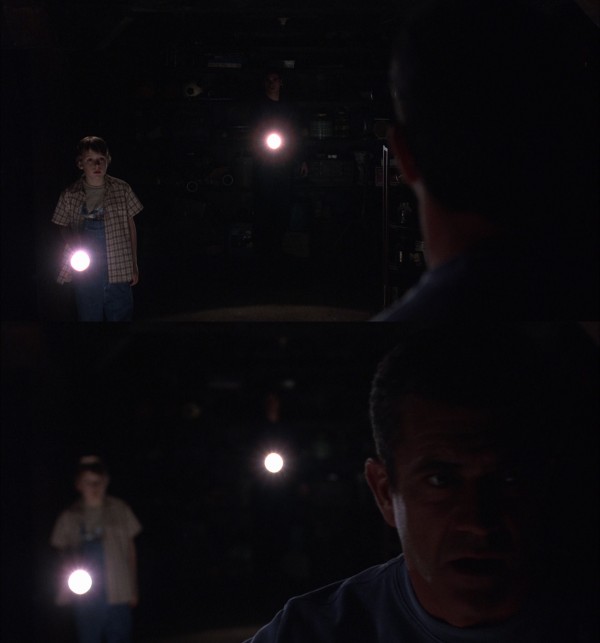

The first flashlight proper occurs about 35 minutes into the film. It immediately creates a sophisticated layer of symbolic interaction between humans and aliens (like the similar flashlight/searchlight designs above also connect the two species).

Highlights from the dark: the cellar sequence

Late in the film, the family barricade themselves in the cellar. In this sequence flashlights become the main governing principle of imagery and mise-en-scène, aided by various other, rhythmically recurring narrative and stylistic figures – for example, strange ellipsises in the storytelling. On the whole, the sequence is a textbook example of how to stage events a confined, seemingly visually dull space in vigorous, inventive and elegant fashion. At the same time, all of this convey the confused and bizarre nature of the family’s predicament.

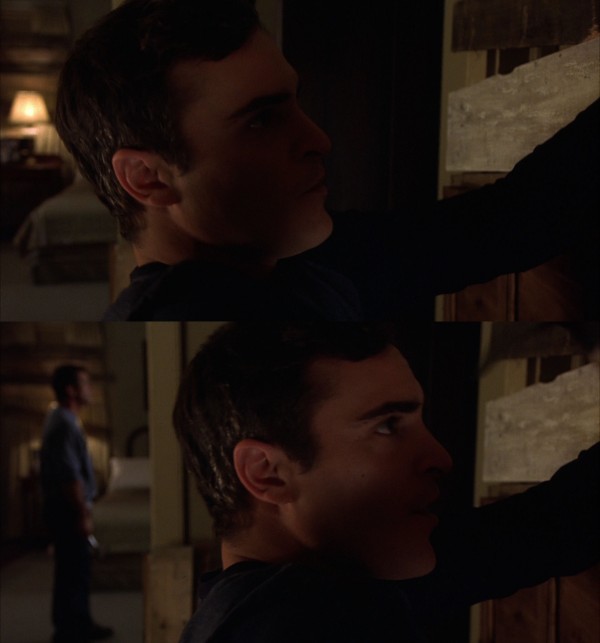

Flexing his newfound maturity, Merrill decides now is a good time to give Graham a talking-to: “Listen…there’s things I can take and a couple things I can’t. One of them I can’t take is when my older brother, who’s everything I want to be, starts losing faith in things. I saw your eyes last night. I don’t want to ever see your eyes like that again. Okay? I’m serious.” The choice of the last word seems to underline the change in him, and the little smile Graham gives in return indicates that he has sensed it too. Like Graham helped Merrill grow by saving Morgan, Merrill helps Graham on his way to heal. The division into two groups – things that can be either taken or not taken – echoes their late-night conversation, where Graham speaks of two groups of people: “Are you the kind who sees signs, sees miracles? Or do you believe that people just get lucky?” The two scenes are also further connected:

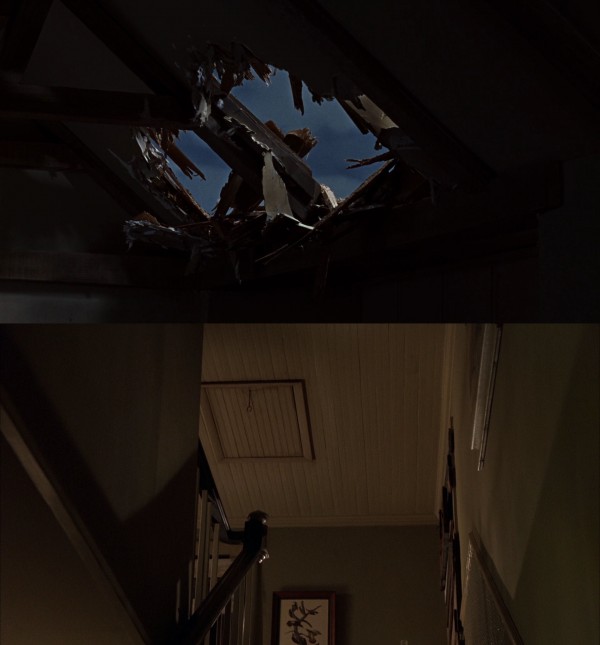

They decide to leave the cellar, which happens in this memorable shot of the cellar stairs, and then the climactic battle with the Nemesis Alien happens.

Windows

Before we look at the ending of Signs, rounding up the usage of windows will make us better understand it. Since the family barricade themselves in a house, in itself a motif, it is not unnatural that also doors and windows should be motifs. (We should also keep in mind that Signs‘ many TV screens can be said to be windows to the world.)

The window of Graham’s bedroom looking out at the backyard is fetishised at key moments of the film. Above, we see it in the opening shot and during the run-up to the pantry door scene. The next time this window is involved comes as the family are boarding up the house. The scene is initiated by the below shot, which is intensely stylised: by an almost surreal depth composition, the immobile posture of Graham, in profile, framed by the doorway, and when he moves out of sight he is revealing the photo that was so important in the film’s second shot:

Now follows the only shot in the film of this window seen from the outside looking in. This may be meant to make it seem like a POV shot from an “invisible” alien, but the main reason is probably to use the same ripple effect from the window pane as in the film’s first shot. The below slide show charts how Graham gingerly approaches it (the shot with the black bottom border is the first of the series), looks out, and retreats without turning his body, in the same sleepwalker-like fashion. As he comes close to the window, his visage is subjected to the unreal wavy effect caused by the window pane. When he looked out of this window before the pantry door scene, he seemed a bit sad as if the idyllic view reminded him of his wife and the happy times spent in the backyard. But now Graham’s face is etched with a strange kind of frozen fear, as if he expects this to be his last ever view of the familiar sight:

The stylisation culminates by the scene ending in a shot that is an exact reverse situation:

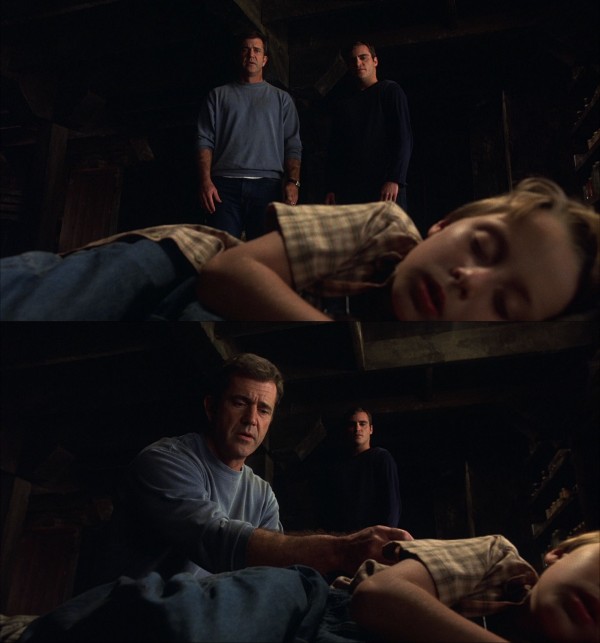

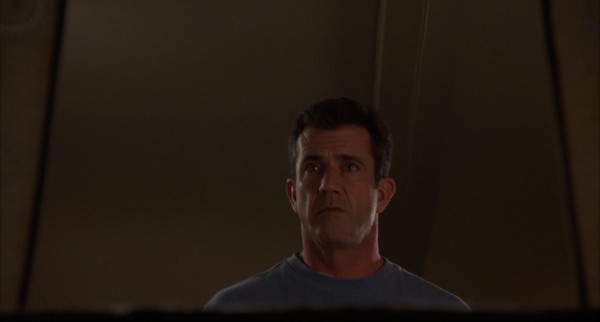

Now we join the film after the battle with The Nemesis Alien. The film’s penultimate shot is a 70-second long take. All through it, except for the moments when the camera pulls down to look at the children, Shyamalan makes sure that the (broken) windows in the background are made to play a part. In a shot that feels jerky and unpolished, their almost-constant presence even seems to form some sort of visual anchor:

After Morgan is revived, the last shot shifts the vantage point to Graham’s bedroom and gives us the third view of the backyard. These views are positioned at even intervals throughout the film, the second one carefully placed very close to the film’s mid-point. They grow progressively brighter:

A comparison of the full views of the opening and closing shots yields many meanings:

It is now sunny and bright. We see much more of the cornfield, the former focal point of fear now resolutely non-threatening. The roof of the playhouse has gone, and with it the stars and half-moons that were bad omens. The stasis of the frozen image of the first view is substituted with the movement of the wind and the four family members, as if they have left the bedside photograph to give life to the backyard. The preserved, “hermetic” harmony of the first view and the photo is substituted with an animated, “alive” harmony.

Something had to happen, to shake the inert family and window view into life. Enter the aliens, who broke the window, and it is very logical to frame the family through it, since they could not have made their personal breakthroughs without the alien threat. Here breaking means healing, as the family have healed as a consequence of breaking the grief over Colleen’s death. At least three of the four characters have achieved breakthroughs (Graham: regained faith, saved son; Merrill: become a responsible person, killed alien; Morgan: belief in aliens and science vindicated, survived). One of their inner demons have just expired, reflected in a TV screen, which is cracked to connect it to the broken window.

The family have reconquered their world. Signs has otherwise been a progressive series of restrictions. As an ex-priest, Graham retreated to the farm. Merrill retreated from the world to join him but is languishing. The first moments of the prologue have a boxed-in feel with its many rooms and doors. Bo hid from the attacking dog in the playhouse, which foreshadowed how the family would retreat into the house from the aliens. Later they were forced down into the cellar. Even Merrill’s decision to start having long TV sessions inside a closet – a house within a house exclusively devoted to his obsession with aliens – is emblematic of their diminishing freedom. (We remember how the hero of Unbreakable hid his secret file of football clippings in a closet.) The film resounds with bangs as doors are closed and windows nailed shut. But at the end, the circle expands again. First they win back the house from the Nemesis Alien, then we now see them outside, and soon Graham will be ready to move into the world again.

The family now sit as a tightly knit unit – in marked contrast to the prologue, which studiously introduces them one by one in isolated pockets. Their current bonding is a culmination of a small yet important strand of physical proximity. One could argue that the below scene is the strand’s embryonic moment – and certainly one of the film’s sweetest – as Morgan just holds out his hand without looking, reflecting the ingrained, intimate bond between the siblings:

Touching is also key in two of the film’s most memorable moments, involving the babycall:

In the car scene, it is when all four family members touch each other that the alien signal becomes clear. In the dinner scene’s post-quarrel reconciliation, the babycall suddenly sparks to life during the collective hug. This last signal is accentuated by an almost inhumanly cold camera movement down the table, revealing the babycall in the foreground. The alien signals appear not only as if conjured up when humans touch each other, but as if symbolising deep fears in all humans (the collective unconscious?), which fits the notion that the farm is a microcosm of Planet Earth. The cellar scene is also important: here the family sit in two pairs close together, while Graham says to Morgan, “Feel my chest. Breathe with me. Together. The air is going in our lungs. Together. We’re the same. We’re the same.” This naked admission of the necessity of bonding seems an important step in the family’s healing.

The transition between the penultimate and last shots is made through a dissolve (one could even say this device substitutes for the ripple effect of the now broken window):

On some level, the dissolve encourages the feeling that everything outside has occurred in his mind, an arena where his fears are played out as part of the dream aspect of Signs. The alien-infested cornfield even seems to be spring from his brain. The transition also echoes the dissolves involving mobiles – here and here – which merged aliens, inner demons and dreams. Finally, the dissolve creates an eerie sense of unity: for a moment, the inside is the outside and vice versa, perfectly summing up the Signs‘ uneasy relationship with reality. The camera is looking out at the yard, but at the same time, behind Graham, we see the vantage point of the camera that looks.

The end of Signs

The last shot presents the film’s first coherent view of Graham’s bedroom. It pains me a bit to reveal that there is a rather bad mistake in the film here: the interior layout does not fit the exterior layout in terms of the number of windows and the direction they face. As a side effect, it is impossible to determine which window is the iconic one when viewed from outside – for the sake of added meaning, I would have loved it to be the one we see here and here. (There are other continuity problems with the bedroom space: at one point the bureau is placed differently and in the second window shot the swing set is clearly in a different position.)

This shot presents a small cascade of balanced closings. We have seen the iconic view from the window three times, and this is the third time he has come out of this door. These three junctions happen at the film’s start, mid-point and end. Both the first and last shot of the film start on the window. Both the film and this last shot start on a window and end on a door. The film starts and ends with a closed object (window and door respectively). The window and the door are positioned at opposite ends of the room, and the camera has now connected them, moving in a half-circle – which includes another important motif in this cascade of closures.

Let us backtrack a bit to the moment he came out of the door. It is never opened more than narrowly, which leads our thoughts to an earlier scene (where he wore similarly dark clothes):

As Graham looks towards the door (in the bottom shot), the camera immediately starts to pull back, to reveal a dress:

A multitude of meaningful details were revealed when this situation was discussed in the second article, but there is yet another layer that only becomes apparent in the light of the film’s ending. Colleen died and never got to use the dress. In his grief, Graham turned away from God and “hanged up” his priestly attire. Both of these disrobements were (in)directly caused by the same man, Ray Reddy, precisely the person who is on the phone with Graham in the dress scene. But in the last shot, as a healed person, he is wearing the Reverend uniform again. There is a connection between the dress scene and Graham’s appearance here at the end, marked by doors, the visual echo of them being narrowly open, and clothes – both the dress and the Reverend outfit are clothes that show their owners at their best.

There is even an intermediary stage to Graham’s regaining his proper clothing, for after the dress is revealed, the next shot starts like this:

The camera is positioned as if to give maximum impact to the fact that Graham now has put on a sweater of the same colour as the dress. (The door in the shot, as a motif, also contributes meaning.) Graham will wear this for the rest of the film. Colleen dying in a blue jacket, the lighting at the accident scene, Merrill wearing blue for most of the film, Bo with the blue necklace in the aggressive dog scene, the dinner tablecloth and the playhouse roof (both here) also seem to fit this scheme.

As Graham leaves the film, he seems calm and content. The ominous noises from unseen aliens during the siege are substituted with an entirely different flavour of off-screen sound, as we faintly hear Merrill speaking warmly and laughter from the children. This helps bring about a subtle closure of a thematic thread about religion. When Graham and the sheriff inspect the first crop circle, Graham suddenly stops, saying, “I don’t hear my children”. Neither does he when he listens at the door of the children’s room in the prologue, and before he joins them in reading the book about aliens he becomes aware of their presence only through whispers.

Graham’s line of dialogue is applicable to another Father as well, since Graham’s rejection of religion means he is no longer a Child of God and can no longer be heard by Him. Morgan has rejected a father too, and refuses to let Graham comfort him after he has killed the dog. It is notable that “I hate you” is said to two fathers: Morgan to Graham when the latter refuses to say a prayer before their “last meal”, and Graham to God (twice, for good measure) when Morgan has his asthma attack in the cellar. As a priest, Graham is addressed, like God, as “Father”. In Signs, Graham (and God too?) seems to be the usual Shyamalan mentor character: Graham is almost worshiped by Merrill, and at one point he is teaching his whole family to breathe. And Morgan is a mentor for his little sister.

Graham appears to be afraid of God: when the aliens are massing for a global attack, the fear on his face is palpable (because he has to face a day of reckoning without God on his side?), and when the news anchor says “God be with us all”, he virtually runs away, to go on barricading the house. In his withdrawal from the world, too, he is an archetypal Shyamalan character, and Signs is a series of progressive withdrawals into ever more restricted spaces. Morgan is challenging his father already in the prologue by insisting spitefully that “God did it” about the crop circle, but Graham’s denial and urge to explain things away are evident just afterwards: “Look, Lee, I don’t even care if it was him. (…) See, it was strange finding the crops that way. The kids were confused by it, and, uh, it’d sure take the strangeness away if I knew it was just Lionel and the Wolfington brothers messing around, that’s all.” Graham’s approach to Morgan’s asthma attack seems an important stepping stone in reconciling himself with at least an aspect of faith: “Don’t be afraid of what’s happening. Believe it’s going to pass. Believe it. Just wait. Don’t be afraid. The air is coming. Believe.”

Symbolically, the aliens may not just be inner demons, but devils sent by God to test mankind. It is notable that they are never seen using technology and do not even seem to have clothes (more on this angle here). A user on this thread on Reddit says it well: “The little girl is an angel, thus her water becomes holy water, and thus it can kill the hellspawn. When you factor in the priest and all the religious themes of the movie, this really starts to make more sense.” In this reading, it is God who speaks through Colleen’s dying words, but in addition the actual defeat of the alien happens through a collaborative effort by the family themselves.

Graham moves from “We are all on our own,” in his unsettling conversation with his brother, to “We’re the same,” in the cellar when the whole family breathe as one to save Morgan from the asthma. It is also as an unbreakable unit the family sit together at last, beneath the iconic window of Signs.

*

Addendum: References to other Shyamalan films

To all the films of the pentalogy:

The usual themes and motifs: mentor characters, faith, finding one’s purpose, innocence (in Signs the little girl), withdrawal from society (Graham has given up being a Reverend, retreated from life, and all the action is seen from the vantage point of the farm). They are somewhat less evident in Signs, however, as a central Shyamalan motif: secrets. The characters themselves do not have any secrets, but the story itself provides some: the true nature of the crop circles, the aliens and their invasion, and the last words of the hero’s dead wife are all gradually revealed. The aliens have an important secret: their own disastrous vulnerability to water. And as usual, perhaps the ultimate Shyamalan keyword is uttered, as Morgan exclaims, “They’ll know our secret thoughts,” when he realises that the family forgot to bring the tinfoil hats with them into the cellar. Finally, the cellar-as-location motif is at its most prominent in Signs.

The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable:

- the opening scene starts out in a disjointed, slightly claustrophobic mood, with lots of doors in a somewhat labyrinthine space – this is a mild echo of the openings of the previous films: Anna in the cellar in The Sixth Sense, and Elijah’s birth in Unbreakable in a space with lots of mirrors, shattered sight lines and confused geography

- when Graham rests his head against the cellar door when the aliens try to break in (“I’m not ready,” he says), the same peculiar, jittery type of slow-motion is employed as on several occasions in the previous films

- Signs is the third film in a row where a grown-up goes down on a knee to speak to a child:

The Sixth Sense:

- a bitter family quarrel erupts at the dinner table with the adult behaving unreasonably, like between mother and son in TSS

- the Brazilian birthday video echoes the wedding video and the videotape of the poisoning in TSS

- the aliens break the windows of Graham’s bedroom when they enter the house, replicating how the home invader Vincent gains access, also in the family bedroom, in TSS

- a TV anchorman is played by Greg Wood, who also portrayed the bereaved father in TSS (in the earlier film he is watching a TV, in the later one he is on TV being watched):

- there is a plaque commemorating Merrill’s baseball record, like the citation honoring Malcolm in TSS – and both are used for reflections:

- the markings on glass panes are quite similar – dominated by diamond and rectangular shapes – to those inside both households in TSS:

Unbreakable:

- the aliens’ vulnerability to water mirrors the Unbreakable hero’s weakness of water

- during the dinner quarrel Morgan says he hates his father because “you let Mom die,” a similar ruthless attack on the weakest point of the person closest to you occurs during the kitchen scene in Unbreakable, where the father threatens to leave the family if the son does not lower the gun

- the iconic window shot is quite similar to the view from the 13-year-old Elijah’s apartment window, both in framing, elevation and the playground equipment:

The Village:

- the aliens are threatening the farm much like the monsters are a threat to the village, with both entities remaining largely unseen

- Merrill holds several baseball records, while in The Village Lucius holds the record in the game young people play to see how long they dare stand at the dangerous village perimeter – both characters are played by Joaquin Phoenix

- when doing the dishes Morgan and Bo splash water at each other, while in The Village, during the same activity and with equal merriment, two little girls splash water at each other’s dishes

Lady in the Water:

- Morgan is brought back from the “dead” like Story in Lady in the Water, and through immense efforts from the hero

- the book on extraterrestrials is remarkably accurate in its predictions, making its story become true, not unlike the ancient myth of the sea nymph becomes real

- the book is constantly providing new information, like new aspects of the myth and The Blue Word are constantly revealed

- the sense of being part of a larger predestined puzzle in the climactic situation in Signs resembles the situation in Lady in the Water, where as Story puts it, “…the world will line up and reveal we are on the right path – that the universe will give us signs”

The Happening:

This set of references only comprise the Shyamalan pentalogy of films from 1999 to 2006, but there are so many similarities between Signs and The Happening that it feels natural to point the reader to this summary in the second article on the later film. The two works are closely related, in a milder form of how Unbreakable can be regarded as a re-imagining of The Sixth Sense.