After Earth, Part II: Figure in a landscape

The author is also behind an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s five films from 1999 to 2006. There are several articles on each film: The Sixth Sense (1999, here, here and here), Unbreakable (2000, here, here and here), Signs (2002, here, here, here and here), The Village (2004, here, here and here) and Lady in the Water (2006, here and here). All the articles can also be accessed through this overview. There is also an article about Split (2016). This is the second of two articles about After Earth (2013). The first one is here.

*

Even though After Earth is not among M. Night Shyamalan‘s best works, it is made with considerable finesse and craftsmanship. The first half hour is very uneven but the last hour is excellent. Arguments for why it is a much better film than commonly held can be found in the first article.

In the following we are going to see how Shyamalan, faced with commercial and artistic restrictions (see here) luckily not applicable for his early films, has managed to downscale his directorial personality but not losing it. This author does not claim that the devices and methods applied to After Earth are in any way unique or the result of some towering directorial genius. The aim is simply to get at the truth of how this specific film is working. It is hoped, however, that afterwards we can agree there are indeed skill, elegance and beauty in After Earth.

Without further ado we will delve into three brilliant scenes: the poisoning, the dream on the raft, and when Kitai is caught in the cold and the aftermath. (Other outstanding situations are already covered in the first article: the sequence when Kitai reaches the tail section of the ship, and the climactic epiphany on the mountain). The rest of the article is devoted to an always rewarding approach to a Shyamalan film, namely structure: the miniature motif, the embrace echo, some visual rhymes, and examples of the staging of scenes. There are also a couple of addendums, this one deals with the opening of the film.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of After Earth, here is a brief outline of the plot.

*

Three brilliant scenes I: The poisoning

Early in Kitai’s journey he gets poisoned by a leech. While rapidly losing sight and bodily control he must administer an antidote. It is a scene of intense urgency, with fine acting by the younger Smith and solid support from his father who must keep calm amid Kitai’s panic.

Many disciplines in Shyamalan’s team here come together beautifully. The make-up for Kitai’s swollen face is terrifying and convincing. The calm, mournful, hymn-like music of James Newton Howard offers a serene counterpoint to the desperation on the screen. The mood is further enhanced by Peter Suschitzky‘s more or less fixed camera position looking up at Kitai. And not least at the background, where nature plays beautiful support: trees are bending and towering over Kitai eerily, a wide angle lens keeping both foreground and background in focus, with a distortive effect.

A brilliant and “invisible” touch is that the worse the boy gets, the background is getting lighter, as if to signal approaching death. As Father announces Kitai have to administer the second and last stage, there is a marked difference in the background light. The angle is suddenly a bit steeper too, more directed towards the heavens, and the trees also look thinner, more precarious.

There also seems to be a discernible general brightening during the first stage (although not 100% consistent): judge for yourself in this addendum, which lists all 13 shots of Kitai from this camera position (shot 1-8 first stage, shot 9-13 second stage).

Three brilliant scenes II: The dream on the raft

You are alone in a wilderness where Man has been extinct for a thousand years. Not only that but you are on a raft in the middle of a river. Then suddenly a human being bends down over you. This author still remembers the exquisite feeling of disorientation from the following gentle shock (a slide show can be restarted from the beginning by clicking on the image to make it large and then return):

The above breakdown of the shot into its particulars shows that the effect does not only come from the girl bending down. It is extremely discreet, but the camera first closes in minutely and then gradually reframes the shot upwards, so both girl and camera are co-operating organically in a unified movement. The scene abounds with delicacy: first a disquieting shadow falls over him, then her hair enters the frame with bewildering effect. (The third stage, it can be difficult to see without enlarging.)

No more Ms. Nice Girl! In this two-second shot, delivering a ruthless jolt to both Kitai and spectator, Senshi takes on a demonic visage to frighten him into waking up. Not only is her voice turned into an inhuman shriek, but there is a visual whiplash: her head twists around to give her appearance a physical force too, while also hiding her disfigurement for a split-second. (For many viewings this author thought she merely applied a generic horror film face to do the job, but this is likely her actual death mask after having been mutilated by the Ursa.)

Kitai must be woken up because he has fallen asleep on the raft and a deadly cold period is coming fast. Is it just his subconscious manifesting a sense of danger as a dream, or is she a true apparition, a ghost? A spiritual messenger? Shyamalan keeps everything open.

The shot just before this scene (see slide show below) poses a fascinating enigma though. Is it merely a general passage-of-time-marking, atmosphere-creating, scene-establishing shot? Or does the downward movement of the camera, finally veering to the left as if towards the shadow, indicate a spirit searching him out? (Or is it the point-of-view of the giant bird that has been seen to follow him?) The fact that it is also breaking the pattern by being the only overhead shot in the film that looks down from some height – otherwise we are never higher than this or this – encourages us to bestow special significance upon it.

The first seconds on the raft are replayed near the closure of the film: in the repetition, in a tighter and more intimate framing, we (and he probably) finally get to hear her resonant words, which are another wake-up call: “You’re still in that box. It’s time to come out.”

The final framing just adds to the general feeling of closure in the epiphany phase of the climax. Kitai is centred not only visually but emotionally, and the removal of the sister from the frame signals that he has let go of the unprocessed, crippling grief for her, and after the epiphany he is strong enough to cope with the world alone.

In the hostile environment of the film this 105-second scene is an oasis of serenity and warmth – an emotional equivalent to the planet’s thermal hot spots. In a poetic, scaled-down mirroring of humanity’s extinction on Earth ages ago, the girl’s life was also extinguished, years ago. Jaden Smith is wonderful here, Shyamalan making great use of his naturally beautiful features, and has fine chemistry with a natural Zoë Kravitz as the sister.

The structure is also nice: the scene is bookended with two shocks, one poetic, one horrific. It also starts and ends with a wake-up call, for the reason he opens his eyes, even though from a dream-within-a-dream, is the fact that, after the initial inaudible whisper, her first line is: “Wake up. It’s time for you to wake up.” It also echoes Father’s earlier command that Kitai must wake up after the paralysis that followed the poisoning, also in that case to avoid a cold period.

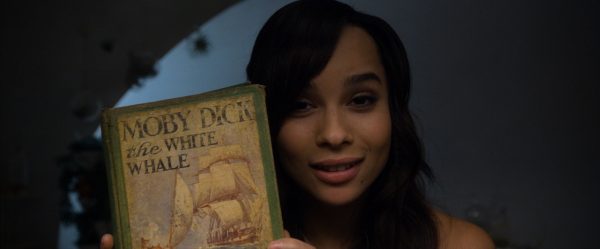

By the way, this is Kitai’s quote from “Moby Dick” (imperfectly recalled, with his missed words in brackets): “All that [most] maddens and torments; all that stirs up the lees of things; all truth with malice [in it]; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle…” The full quote can be found here (item 3), with an explanation. It is supposed to be “the existential heart of the book”.

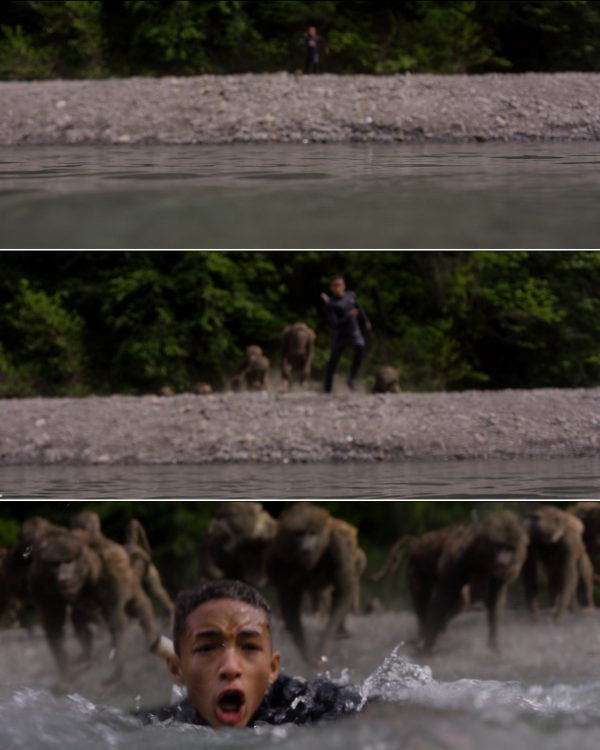

Three brilliant scenes III: Caught in the cold and the aftermath

An inventive take on the mobile point-of-view shot, made famous by Hitchcock, one of Shyamalan’s heroes. The event is depicted with a detached otherworldliness and becomes even weirder by the methodical way the movement stops and starts three times during the journey. (The above simplified slide show leaves out most of these pauses.) The dragging shot lasts 16 seconds and added to the 14 seconds of the preceding close-up, this segment’s duration and the hero’s passivity help create a mood of frozen stillness.

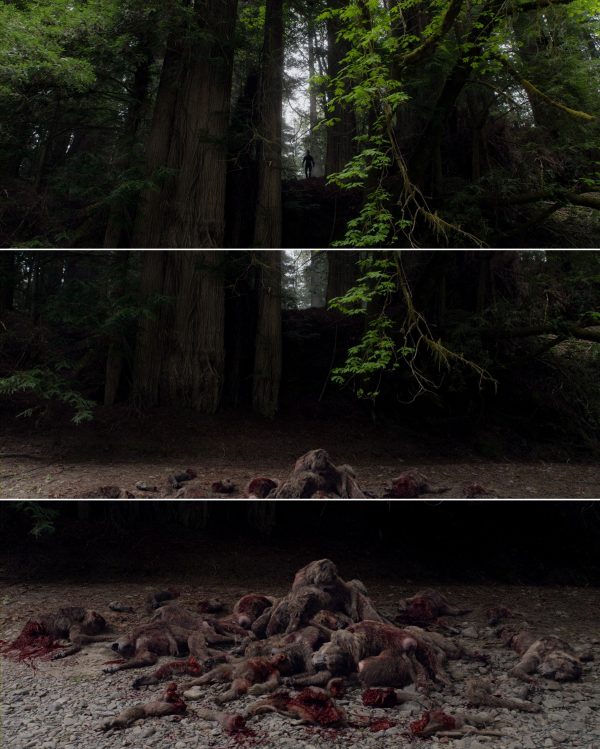

The next day Kitai wakes up, warm and snug inside a web of thick vegetation. As he clambers out, we get a slow “revealing shot”, whose foreground at first seems to be an unusual kind of rock formation covered with scales…

…but as soon as the camera reveals a strange bump we feel it must be something else, and then the camera pulls back while Kitai seems to become emotional and touches the object. Suddenly, there is an abrupt change to a high angle, revealing not only the object but also the fact that it is probably the same bird that attacked Kitai as he flew down from the clifftop:

Here a tender echo is set up: like the bird touched its offspring to check if they were dead, Kitai is repeating the gesture, touching the head of the bird, the next casualty in this chain of death.

The shot’s perspective makes Kitai seem the same size as the offspring in the foreground. This effect might be intentional, for after having observed how Kitai helped defend its hatchlings against the predators, the bird has indeed adopted a guardian role for Kitai. This is why we have seen it in the air above Kitai on a few occasions. (It is also possible that it has eased his journey by taking care of dangers behind the scenes, something that could account for Kitai having encountered relatively few problems.)

The dragging-along scene represents the second time the bird has transported him to a nest, the first time as food, the next to save his life. The situation is also a repetition of Kitai’s past trauma. In the flashback his sister hid him in the box before she gets killed by the Ursa. Here the bird has tucked him away in a nest before it perishes from the cold.

Like his sister sacrificed herself to save him, the bird seems to have done the same. The exact reason for its death is left unclear, however. Has it lost its will to live after losing its offspring? Was it injured fighting the predators? Perhaps this particular hot spot was very small, without room for a giant bird, and the bird perished in the cold soon afterwards? Was it already weak, and might that be the reason for the stops when it dragged Kitai?

Anyway, the episode seems a formative step on Kitai’s road to resolution. The nest is a similarly enclosed space as the box. But instead of cowering like in the flashback, he stood up against the predators, the equivalent of the Ursa of his childhood, and tried to save the hatchlings. He now stands beside the bird pondering the self-sacrifice of his saviour, the equivalent of his sister. The film lingers on the situation, loading it with special emphasis during the final two shots of the scene:

Let us briefly go back to the out-of-focus POV shot. As a measure of Shyamalan’s careful attitude to detail and coherence, in a shot that did not have to be more than an unspecific blur, one can make out the shadowy figures of several birds flying by (not discernible in the screenshot though). This underpins the idea that all living entities are racing to shelter from the cold, but it is also in preparation of the importance of the bird.

The miniature motif I: In the towering forest

After Earth tends to evade close-ups during Kitai’s trek, and as for another technique generally regarded as involving, there is only one hand-held shot in the entire film. Instead Shyamalan is looking for a different kind of immersion. The boy is consistently shown as a minuscule part of the environment, not seldom merely glimpsed among trees and vegetation, while the forest is towering over him.

Incidentally, Peter Suschitzky was one of three cinematographers working on Figures in a Landscape (1970), one of Joseph Losey‘s weakest films but nevertheless interesting for its similar, often dazzling use of landscape, and he also shot Matteo Garrone‘s pastorally ravishing Tale of Tales from 2015. (Another parallel: the driving force behind both the Losey film and After Earth was its central actors, to whom the projects were highly personal, Robert Shaw and Will Smith, respectively.)

Consequently, there are very few shots from a great height providing an overview of the landscape. Granted, when Kitai has reached the clifftop there is a grand view of the forest stretching out below him, and there is also a similar vista as soon as Kitai has climbed the hill directly above the wreck. Both shots are taken from the level of Kitai’s position in the landscape, however.

From a higher perspective, there are only two shots (here and here) from some height, both of the river and not yielding much overview. Much like we were totally locked in to the vantage point of the family trapped inside the house in Signs, we are confined to Kitai’s experience of traversing the forest.

The miniature motif II: The receding principle

Another variation of the miniaturisation motif is when it occurs as a process within a single lingering shot. This turns out to be a governing principle of the film and is always used to set the scene for a momentous event. It starts already as Kitai is leaving the spaceship:

The early segment on Nova Prime is a weak part of After Earth but it contains an idea that is not only breathtaking in itself, but prepares a delightful visual rhyme:

Both shots come at pivotal moments: next Kitai is going on a space mission; soon Kitai will jump off the cliff. (In an amusing echo, Kitai is about to fly both times – the last time on his own power, using the wings of his uniform.) They are both leisurely intermezzi before dramatic events and end with a dwarfed Kitai – yes, this sounds familiar: it is essentially the same device as in the previous examples, except that the dwarfing of Kitai does not happen through him receding from the camera, but the camera is moving away from him.

The receding variation of the miniature motif is so deeply embedded in the film that in itself it is difficult to spot. It can hide in the narrative because it always plausibly coincides with a natural action from the character. It was only late in the process, after many viewings, when I started looking at a complete screenshot gallery to systematise types of shots and formal devices, that the type of the receding character was uncovered.

On the other hand, the visual rhyme of the helicopter shots was easy to pinpoint on early viewings due to their dazzling visual impact. But it was precisely this grandstanding that made them resistant to being seen with the same analytical eye as the quieter shots. The camera instead of the character moving also made it harder, of course.

But with these new eyes, suddenly another scene can take its rightful place as a cog in the film’s governing machinery, namely the climactic three shots of the final replay of Kitai’s trauma flashback:

Again Kitai is miniaturised, by a (different type of) camera movement. The narrative position directly preceding Kitai’s epiphany means that also this instance of the motif is “signalling” a pivotal event. (The last stage of the epiphany is Senshi’s apparition saying: “You’re still in that box. It’s time to come out,” directly connecting to the above scene.)

The box keeps Kitai safe but also traps him. In similar fashion the teenaged Kitai is trapped inside the trauma of his childhood. He is still the little boy fearful of the big world with all its threats, with the Ursa embodying his fear, uniquely equipped to sense it. Kitai’s psychological state could explain the presence of the receding miniature motif, resizing him constantly into that little boy. (Since the flashback is constantly replayed in Kitai’s mind, and in the film, After Earth scores a subtle point by showing there is an actual recording of his defeat of the Ursa – a physical recording replacing a recording of the mind, healing replacing trauma, and which in similar fashion can be perennially replayed.)

In summary, the receding motif appears before the following events: leaving his planet, leaving the spaceship, jumping off the cliff, arriving at the tail section, arriving at the mountain, reaching the plateau of the climax – and preceding the epiphany, and leaving Earth in a healed state.

The lingering pace of the shots seems like a smaller-scale version of Shyamalan’s tendency in his early films to heighten tension by slowing things down, at certain moments in a film that must to a certain degree to conform to a mainstream sensibility and pace, with an average shot length of just under five seconds.

The miniature motif III: Merging with a landscape

Another sub-motif is the presentation of Kitai as a figure often merely glimpsed as part of a tapestry of vegetation, almost entirely swallowed up by the surroundings:

The miniature motif IV: Figure in a landscape

There can be no doubt that long shots are overrepresented in After Earth. We will close the investigation into this motif with a collection of shots portraying Kitai as a figure in a vast landscape.

The following is the film’s most beautiful visual rhyme. It also indicates a meaningful evolution, since the shots get progressively more bare, more essential:

The embrace echo

We talked a little about embraces in the first article. There is a quite extensive pattern at play here.

It is tempting to recall the hangar scene, where although Father was just helping the veteran, he was seen leaning his head on Father’s shoulder, in some sort of bittersweet comment on the many other hugs in the film. Is Shyamalan massaging our subconscious here? The action represents the intimacy Kitai is craving, but he has to settle for leaning against an object, while the episode with the veteran also underlines the fact that the way to earn his father’s respect and affection is through military prowess.

It is telling that Kitai could not care less about the salute – the highest honour his father can bestow on another person, and something that Kitai craved at the start of the film – he just wants to embrace his father. The film’s last lines – Kitai: “I want to work with Mom.”; Father: “Me too”– seem to be more than the usual standard, self-consciously lame joke where the generic hero pretends the mission has been so strenuous that it would be better to quit.

It sounds like a genuine decision, from both of them, to leave the special status of military life for a quieter life with his mother. Father also announced his coming retirement at the start of the film. Kitai is thus eschewing his newly acquired ability of ghosting, and not least his status as a celebrated hero, through defeating the Ursa. He seems already to have won fame, just see the awe in the look of the Ranger who plays a recording of the killing, made by Kitai’s backpack camera.

There is no overt criticism of military life and values in After Earth, but there is at least an ambivalence. Kitai looks up to Father, but there is the parallel of the veteran, who also worships Father, but military life has left him physically ruined and their mutual salute ends in pain and humiliation. And Father’s salute to Kitai at the end is simply ignored. If After Earth was meant as a gung-ho celebration of heroism it is awfully muted.

They are perfectly aligned in agreement that a quiet life working with Mom is a great idea. This takes the notion of them thinking as one person, which started with the development of a “mystical” connection even when communication was down – discussed in the first article (starting in earnest here) – to its conclusion.

The last we see of Kitai is a 24-second shot where the camera gradually excludes Father, indicating that the boy is now able to stand on his own legs in life. (This could fruitfully be seen in conjunction with the last reframing of his face, which excludes his sister, in the dream on the raft.)

Visual rhymes

In the first article we already discussed the climbing and the cliff as echoes that help create closure. And we have so far pointed out the rhymes of Senshi’s whisper, the helicopter shots and the overhead shots. There are more, however, in the structural network of After Earth.

The firing of that distress beacon and its aftermath employ light as an elegant motif (as demonstrated in the slide show below): The beam shooting up from Earth is transformed into a blue circle that spreads outwards. It ends with a blinding flash, and then light motif returns in the glow from a cutting device opening up the spaceship – the darkness seems to indicate that it has now lost power (conveniently to allow the upcoming light play its part in the mise-en-scène) – and then it is the turn of the rescue team’s flashlights to participate in this relay of lighting. In nice contrast, the next scene opens with the overwhelming brightness of the sickbay.

During the epiphany Shyamalan fixates on Kitai’s bloodied hand. Blood was central to Father’s epiphany of his first ghosting too, according to his monologue: “I can see my blood bubbling up mixing with the sunlight shining through the water. And I think, ‘Wow that’s really pretty’. And everything slows down.”

So this mixture of the dreadful (the blood) and the beautiful (the vision) is undeniably important, like Kitai is using the bloodied hand as an instrument in grounding himself. Let us then chase down the small but persistent hand/blood circuit running through the film.

After the film’s hyperdramatic start (more about that here) with the spaceship in distress and Father blown away by an explosion, there is a sudden cut to Kitai lying on the forest floor (below). We could believe he was thrown out of the spaceship by the crash, but the shot is actually from the aftermath of the poisoning much later in the film. (Technically, I guess this makes the entire film until we catch up to that point a flashback, but I have chosen not to treat it as such in these articles.)

From this position he ostensibly gives us a “history lesson” in voice-over about how humanity found a new home on Nova Prime after having had to escape Earth.

Staging

As we have pointed out time and again in these Shyamalan writings, his perhaps greatest strength lays in mise-en-scène. Within the confines of this type of film, which demands a far less formally adventurous approach, it comes across in After Earth on a smaller scale, in shorter and less visually stylised shots.

In the first article we already discussed the “curtain” scene directly after the crash, one of the best, and very Shyamalanian, visual ideas of the film. We also looked at a couple of scenes inside the tail section as examples of how his camera, even though somewhat distanced, behaves like a living, sensitive, intelligent being – not something that is merely pointed at the action to record it, but an entity that is breathing together with it. So let us complete the picture.

Father’s monologue about his first ghosting is told through long takes, interspersed with lingering cut-aways of a spellbound Kitai. (The 61-second start of the story is the longest take in After Earth.) Both father and son is captured with an unmoving camera, bonding them, but after Father have finished recounting his epiphany he says: “I don’t want that in there any more,” (about the attacking Ursa’s pincher in his shoulder). At this turning point of his story, the decision to act, something happens:

Here a reveal happened through a cut. Moving the camera, however, to gradually reveal salient elements of the narrative is often more elegant and part of any director’s toolbox. Shyamalan’s use of it is not in any way revolutionary but is applied with unfailing elegance.

It is not as important in After Earth as in its “companion film” The Last Airbender though, where it is an extremely consistent part of that film’s visual strategy. In this and the first article we have already discussed the helicopter visual rhyme, the reveal of the bird, as well as Kitai’s approach to the tail section revealing the wreckage and the landscape beyond, and his movement through the tall vegetation to the field in front of the mountain of the climax.

We shall end this article with some other examples, which provide the bonus of an often beautiful tour of yet unseen parts of After Earth. (The revelation of the Ursa waiting for Kitai in the cave, perched high above his head, is also nice but the scene is too dark to reproduce very well in screenshots.)

We round off these two articles about M. Night Shyamalan‘s pleasurable film After Earth with another stirring shot from beyond the heavens, where a ship modeled after the aquatic ray is about to swim in the sea of space.

*

Addendum A: The 13 poisonous shots

Here are the 13 shots of Kitai in the poisoning scene from a certain camera position (shot 1-8 details the first stage of administering the antidote, shot 9-13 the second stage).

Addendum B: The start of the film

The opening of After Earth is quite audacious, possibly so as a creative way of implementing cuts deemed necessary due to poor test audience reactions and the need to have an exciting start. It works quite well, however. There are marked contrast in sound level. The company logos are silent, abruptly followed by the ear-wrenching cacophony inside a mortally wounded spaceship.

Over this we see three snippets of the 26-second scene about 21 minutes into the film where Father is calming a panicked Kitai as the spaceship is heading for an emergency landing on Earth. The alarmed voices on the soundtrack belong to the pilot and navigator, but their exclamations are taken from the previous scene in the cockpit.

Father is blown away by an explosion and next we see Kitai lying on the forest floor, as if he was thrown out of the ship on impact. But this is taken from the aftermath of the poisoning and occurs at about 43 minutes. Contrast in sound continues for this shot is dead silent. Then his voice comes on the soundtrack, kicking off the “history lesson” with the historical backdrop for humanity leaving Earth and settling on Nova Prime.

Interestingly, these two shots seem to be from different takes – even when he will eventually come to rest on the ground in the continuation of the bottom shot (we don’t get to see that) it is hard to believe that he can end up in the position of the top shot.