The Happening, Part III: Do you think it could be plants?

The author is behind an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s films. There are several articles on each work: The Sixth Sense (1999, here, here and here), Unbreakable (2000, here, here and here), Signs (2002, here, here, here and here), The Village (2004, here, here and here), Lady in the Water (2006, here and here), The Last Airbender (2010, here and here), After Earth (2013, here and here), Split (2016, here, here and here), and an initial reaction to Glass (2019). This is the third article on The Happening (2008), the first two are here and here. An article on The Visit (2015) is upcoming. All the articles can also be accessed through this overview, which also contains statistical information and links to external articles.

*

I vividly remember the icily electrifying effect of the opening scene of The Happening, a stroke of genius in its merciless, methodical stripping away of our humanity, into machines of flesh whose prime directive was to terminate ourselves.

The existentially panic-inducing vision of normality switched to nightmare reminded me of a scene I saw a year before, in Zodiac, where the couple at the lakeshore are set upon by the killer in a beekeeper costume, announcing their demise in a stentorian voice of the cruellest kind. Where David Fincher played on suddenness and shock effect, however, M. Night Shyamalan took a more subtle, creepier route to a similar destination.

The next scene employs a louder, direct shock approach to a still satisfying effect: at a construction site workers start to jump off a tall building in a mass self-extinction event. You would now expect the sort of masterpiece that mainstream American cinema can give us: a highly dramatic story, staged with such elegance, invention and impact as to lift it up to a plane of great resonance.

What we get instead, after a tolerably engaging classroom scene, is a gradual, almost systematic dismantling of everything that made the first two incidents distinctive, infectious cinema. Watching The Happening is like being trapped inside the mind of Kevin Wendell Crumb of Split and Glass: two split identities, one delivering suicide scenes of an unflinching nature as well as other intermittent moments of resonance, and another identity insisting on interrupting the program with quirky humour, kooky characters, vague personal conflicts, nebulous character motivations, and at times inexplicable behaviour.

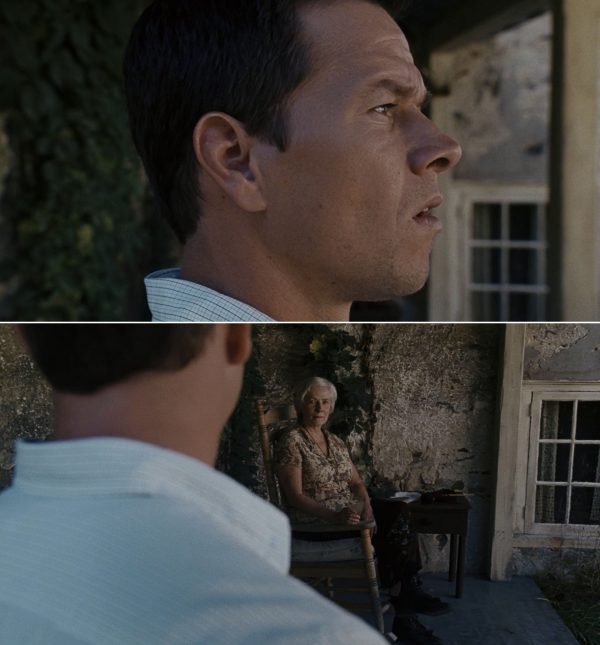

It is not until the third act, as the three protagonists arrive at the isolated house of the hermit Mrs. Jones, that the film settles into a consistent mode. Considering the excellence of this part and the fact that its tone is faithful to the original vision for the film, which had virtually no humour, it feels safe to say that The Happening would have been a much more satisfying work without its farcical and quirky aspects. I hate it when people blithely opine “this or that film would have been much better with this or that element removed or added” – which is very often lazy guesswork – but after having seen the film 22 times at this point and diligently trying to get it to fully work every time, I feel I have some background to say it.

This third article about The Happening will after a discussion of the film’s themes chart out its inconsistent, problematic tone. This rather negative chapter is contrasted with a very interesting article offering a more positive outlook. The piece ends on a further positive note with a celebration of Ashlyn Sanchez as the eight-year-old Jess. There is also an addendum where the original vision for the movie, a screenplay called The Green Effect, will be discussed, focussing on its many differences to The Happening.

As a further antidote to all the negativity in this piece, I can recommend the first article, which walks through the third act and the two epilogues, and the second article, which takes a look at the often brilliant suicide scenes and examines the film’s motifs, visual approach and references to earlier Shyamalan works.

For readers unfamiliar with the story of The Happening, here is an outline of the plot.

*

Themes

The Happening is the nightmare that follows the bedtime story of Lady in the Water. It is also the ultimate continuation of the only fleetingly glimpsed threats of the three previous films – Signs, The Village and Lady – in that the neurotoxin is literally invisible. And while the earlier threats hid in nature – the aliens in the cornfield, the monsters in the woods, the scrunt in the lawn – the enemy here is nature.

The Happening depicts a suicide epidemic instigated by an external adversary, but we are already indirectly killing ourselves by destroying the planet that is the foundation on which we live. It is suitable, then, that there is an undercurrent in the film that the fear and violence residing in our minds – our internal neurotoxin – can be as dangerous as the threat from nature.

Before he rang the bell, a soft creaking had started – from Mrs. Jones’s rocking chair it will turn out – a parallel to the creaking from a similarly unseen object in the barricaded house scene, which there too was revealed to be connected to a threat, a tree. The previous death of the story occurred precisely in that scene and it was man killing man, a situation lent extra emphasis by standing out as unique in the film. The fugitives’ attempt to obtain food escalated, and the people inside the house, desperate from fear of the epidemic and governed by irrational ideas about its nature, shot the two teenagers that had joined the heroes, with especially the last victim being killed in cold blood.

One of the film’s best ideas is the disinterested but handsome boy in the classroom scene, well played with effortless indolence by Robert Lenzi, who represents a common tunnel vision: people are unlikely to take global threats seriously unless it affects them personally. He gets a bit more concerned after Elliot says: “The problem is, your face is perfect at 15. Now, if you were interested in science, you would know facts like the human nose and ears grow a fraction of an inch each year. So a perfect balance of features now might not look so perfect five years from now. They might look downright whack 10 years from now.” Besides the pretty-to-ugly process summarising the film’s plot trajectory, this also illustrates how imperceptibly worsening conditions build up into long-term natural disaster. (However badly executed, the central couple’s simmering marital problems, long swept under the carpet but erupting into a suddenly difficult situation, is another example.)

Compared to The Green Effect, the original script for the film, The Happening has been considerably strengthened scientifically. For example, the bees disappearing is a real-life problem which at the time was only starting to attract public attention. (Speaking about topicality, the Iphone arrived just the year before the film and is actively used for playing video clips of far-away suicides and greatly helps them spread virally, a human parallel to the suicide epidemic.) Its science and themes of environmentalism are summed up and discussed in chapter nine (pages 167-188, try Google Books here) of the book “Homer Simpson Marches on Washington: Dissent through American Popular Culture“. (A lot of the science mentioned in the film seem to be sound: red tides are real, plants have defence mechanisms [here, here and here], and they can communicate.)

Joseph J. Foy, the author of that chapter, concludes: “Perhaps what is most needed is a reality check from the likes of a classic M. Night Shyamalan ending, such as that in The Sixth Sense and Signs, when we are pulled back through the story and shown the overlooked pieces that reveal the answer to the mystery – clues that were present all along for those who knew where to look and how to fit the pieces together. Perhaps then governments and their citizens would see the interconnectedness of humans and the global ecosystem. In the absence of such a revolutionary shift in consciousness, eco-horror films serve as a reminder of the nightmarish future that awaits, and they may advance the type of dialogue that can truly change the cultural conversation.”

It could also be that the odd foregrounding of the childish central couple’s absurdly inconsequential marital squabbles is meant to illuminate a lack of perspective among mankind, considering the vast challenges we are facing as a collective. In this well-written review, Richard Harland Smith, who struggled mightily with the film but kind of liked it, says that it is the “collective portrait of epidemic human insecurity that strikes me as the real catalyst for The Happening“. He states that “the real culprit is the divided mind of the modern man (and woman)”, “without honesty, science, mathematics, military might and even religious faith are all doomed as bulwarks against disorder and disaster”, and “The Happening is populated end-to-end with characters who have the knowledge but not the will or the stamina to really live… and whose skittish, half-hearted existence etches mankind as a nonviable lifeform”. He also offers an alternate take on the “You deserve this” sign and strikes an interesting parallel to Spielberg’s War of the Worlds (2005).

With the image of people leaping to their death from a tall building in the second suicide scene, panic and confusion, speculations about a terrorist attack, it is hard to avoid ascribing a 9/11 commentary to The Happening. Also The Village is often taken as a parable of a US after the September 11 attacks, and in Lady in the Water the Iraq War is a constant backdrop.

Harland Smith found that the Crazy Lady’s “iron-spined inhospitality and abject incuriosity about the world around her nails American isolationism pretty squarely. As he did in The Village, Shyamalan shows characters withdrawing from society by embracing antiquity (symbolized here by bookoo needlepoint, Christian iconography and creepy China dolls) in a bid to retain so-called traditional values… values that ultimately fail to sustain them.”

In Mike Thorn‘s article on three films not so often considered together – although when carefully examined, The Happening comes up with an attention-grabbing number of similarities to Signs (here) and The Village (here) – he notes the omnipresence of television in two of the films, reminiscent of the public “watching the 9/11 terrorist attacks play out repeatedly on their own TV sets” and also the protagonists “moving further and further away from the solace of contemporary communication technologies”. (Signs became an accidental comment upon 9/11 since, as per the director’s storyboarding method, it was likely carefully mapped out long before – although adjustments could of course have been made. By remarkable coincidence its most emotional scene, the death of the hero’s wife, was shot the day after the attacks.)

Thorn also points out the different, “chaotic” start to The Happening, with the dog as a curious object of interest (although dogs are also a motif connecting suicide scenes and may also have thematic meaning). But is the “camera lost and bewildered” with “a great deal of The Happening in handheld style, with wavering close-ups of the actors’ uniformly bewildered and horrified faces”? This seems mainly confined to the sequence out in the field – admittedly the most chaotic in the film – but this viewer does not get any handheld vibe. For one thing, the climax to this chaos is marked by a big close-up with the camera making small adjustments to keep him in frame rather than wavering.

(Does Ivy know the whole truth at the end of The Village as the article claims? As discussed here, there is no indication that Ivy understands the real nature of the monster that attacked her in the woods, neither the real nature of the world of “the towns” she briefly encounter on her quest for medicine. She only meets one single person, an underling, not “the gate-keeper of her manufactured reality”. I prefer the exquisite irony of this interpretation, which just adds to the sophistication of this masterpiece.)

In a Facebook thread Jonathan Hastings informally suggested something that might be an avenue for further research: “I think Shyamalan has expressively worked out his themes through the images: the danger of connecting with others vs. the danger of being alone played out in the way the movie uses group shots vs. singles/close-ups (the scene at the end with the speaking tube plays this out metaphorically in the way that Ulmer or Borzage might have).” He thinks that “the progression towards realizing that being in a group is dangerous works metaphorically, and that the way Shyamalan alternates between characters in groups and characters who are shot in such a way that they’re cut-off from the group plays a part in getting that sense across.” In the early classroom scene he finds “something odd/off about the way the exchange between Wahlberg and the student is staged.” Especially interesting is his idea that “suicide here is presented as a solipsistic act; being cut off from all connections”.

I might add myself that the very introduction of the hero is in this class, itself a group of people, where the uninterested, but eventually surprisingly insightful pupil is singled out, and Elliot himself stands out by virtue of being the teacher. The isolation of Mrs. Jones, the Crazy Lady, also appears to be an important player in this thematic arena.

This colour theory by the IMDb user Thesnake908, published as a user review when the film came out in 2008, posits very interesting things about the relationship between blue (ubiquitous), yellow (used very sparingly) and green (the colour of nature). The fact that mixing blue and yellow will yield green forms an especially promising basis, and the user convincingly argues that yellow stands for the happiness that is denied Alma and Elliot (the latter is connected with blue, denoting tranquillity, or reservedness), and it must be earned through rediscovering love (green). The bees in the classroom discussion are yellow and have disappeared, following just after the couple’s big fight that morning. Yellow is also the colour that meant that Jess would laugh, i.e. happiness. Especially this observation is beautiful: “‘I can hear you like you’re right here,’ says Alma, just like their relationship. They were both physically present in their relationship, but in reality they weren’t connected like two people in love should be.”

The theory seems to stand up, but the argument contains some minor inaccuracies: The Crazy Lady does not say “eyeing my yellow drink” but lemon drink – lemons are yellow, however, so no problem – and she is not wearing a shawl but a blouse with plant motifs, and it is Alma who says to Elliot “we have to protect Jess”, not the other way around. The user does not mention that when Elliot is at his lowest point, just before proving his love by walking out into the danger zone to join Alma, his mood ring for the first time is not blue, and might be in the process of turning yellow.

Finally, the theories chapter in the first article discusses the cause of the suicide epidemic, why does it stop and if it has a pattern, and the heroes’ journey to catharsis and the larger society’s failing to do the same. Houses are discussed as a motif and thematical progression in the same piece. Also, have a look here for how The Happening fits into the director’s common themes, motifs and trademarks.

Tonal quicksand

The very first article that was published in this analysis project states: “So, if one is to get anything out of Lady in the Water, one has to accept that in many respects it refuses to follow traditional rules of storytelling. For much of its running time, at any time, without any warning, it may lurch from one tonality to another. Almost perversely, it is during the first fifteen minutes or so, where any normal film would have taken great care to establish a consistent tone to draw people in, that its tone is fluctuating most wildly. As if it were an enigmatic ‘art film’, no particular contract with the audience is attempted.”

I go on to describe a prologue with “seemingly utterly banal narrative, later revealed as a bedtime story, of how ancient Man in its greed parted with a community of wise sea nymphs. It is accompanied by a very solemn voice-over, strangely insisting on imposing great importance on the apparent banality. … Then, suddenly, we are careening headlong into farce. A long scene, in just one take, shows a man in close-up involved in the lengthy business of doing away with an unseen bug. This is accompanied by a chorus of wailing women with exaggerated, silly Spanish accents.”

M. Night Shyamalan has been here before. Several times, because The Village had a habit of inserting slow, oddly-sounding dialogue scenes among the elders inbetween passages of creepiness and lyricism. Sometimes it required some acclimatisation, but tonal changes eventually worked in those films so why not now?

I: A divided approach

In this interview Shyamalan claims that a problem with The Happening is that its tone is “inconsistent”. This is also one of many occasions he maintains that it was supposed to have a B-movie feel and not take itself too seriously. He seems to have aimed for a much simpler film than unusual, with a conventional story trajectory and no twist. In this well-argued review, rising far above the summary executions Shyamalan got during this period, Michael Koresky points out “its weird mix of audience pandering and refusal to play by the rules” and reasonably speculates that the film “might show something of a toll all the criticism and outsized expectations has taken on him.”

With his newfound creative vulnerability of having to shop the script around, throwing himself at various companies’ mercy, it is as if the director had tried to make a traditionally audience-friendly film but his heart was not in it so the “fun” parts did not really work, neither did the casting of likeable but unremarkable actors as the central couple, and in the end he naturally gravitated towards the serious aspects of the script: the suicide scenes and the third act, including the two epilogues.

In the other parts, he cannot play to his usual strengths of mise-en-scène, mood and tension-building often by purely cinematic means. Going for a simpler visual language, as discussed here, he proves himself to be an efficient but not extraordinary storyteller. For a Shyamalan film, his unusually prosaic visual conception for this work only compounds the problem with the lead actors. The merely serviceably shot non-suicide scenes of the first hour are exactly the parts inhabited by Wahlberg and Deschanel, who are left to fend for themselves, with little help from a film-formal apparatus to lift their characters and issues up to a higher plane. (This is a notable exception.) The actors are not up to it and the characters are too thin – it is noteworthy that of all Shyamalan’s eleven films from 1999 to the present, The Happening is the only work in which the heroes are not dealing with a deep past trauma. (Another first for Shyamalan is that The Happening is his first R-rated film, for the violence.)

One also has to agree with Koresky that the threat from the plants never feels particularly horror-inducing – the mood can be eerie, but nothing more, and the intended high drama in the sequence out in the fields simply falls flat – and he compares it unfavourably to other films “visualising” an invisible enemy, for example The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick & Eduardo Sánchez, 1999), and the contemporary Larry Fessenden eco-horror movie The Last Winter (2006). (The film’s third act is not very frightening either, but scores on a number of other fronts.)

II: Humour

The Happening, in the form of a very grim script called The Green Effect, was taken to various studios until Fox decided to back it, on the condition of changes to lighten it up. Thus humour entered the picture, precisely the thing that did not work. The film has numerous similarities with Signs (delineated here) and he seems to have gone for (and we have to guess Fox wanted) the same quirky humour he introduced into his work with that film. But the fun that worked best had to do with the drollery derived from the precocious son and the sweetness of the small daughter, while the purely deadpan (the visit by the no-nonsense sheriff and the trip into town) is well done but not exceptional, and constitutes the only sequence of the early films that wears thin on repeated viewings.

In Signs the mirth was also kept carefully apart from the segments of suspense and mood. Ditto for the much more successful whimsical humour of Lady in the Water, which revolved around a collection of oddballs not that dissimilar from the coterie of The Happening. As we shall see, in the later film the silliness spreads like a virus until it takes over almost fully in the scenes in or around the field, before it is banished from the film in the third act. (This close intertwining of fun and gravity succeeded magnificently in Shyamalan’s 2015 comeback work, the horror-comedy The Visit, however, but rather than Wahlberg and Deschanel, he could rely on four extraordinarily inspired and fun actors, resulting in his perhaps most audacious film.)

In the interview above, however, at least officially Shyamalan seems to take the position that there should have been less of the serious aspects that I have been praising as the film’s qualities. Interviewer: “When The Happening was coming out, you said you wanted it to feel like ‘the best B-movie you’ll ever see’. In your mind, what characterizes a B-movie?” Shyamalan: I think it’s a consistent kind of farce humor. You know, like The Blob. The campy, 1958 debut of actor Steve McQueen, featuring a mysterious, growing amoeba that takes over a small Pennsylvania town. The key to The Blob is that it just never takes itself that seriously.” Interviewer: “Do you feel like people missed that element of The Happening? The self-conscious humor?” Shyamalan: “I think I was inconsistent. That’s why they couldn’t see it.”

The inconsistency runs deep however. The farcical elements do not sit well with the intensely dark backdrop of a graphically depicted suicide epidemic, and the superb James Newton Howard‘s serious and heartfelt score seems to run directly counter to any B-movie feel.

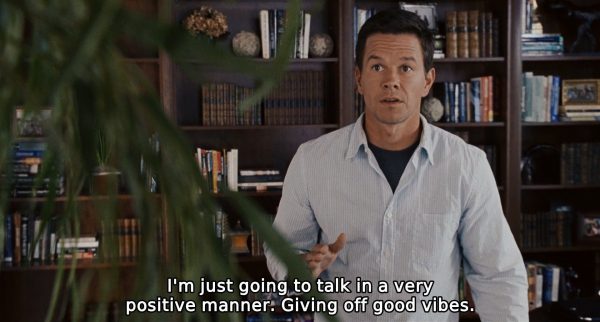

III: Elliot and other jokesters

After the terrifying opening scenes, there is a cut to a high school classroom where Elliot Moore is introduced, a science teacher urging his pupils to come up with answers to why “honeybees are disappearing all over the country”. This is perhaps the only scene where Mark Wahlberg comes close to excelling: he is animated, endearingly eager to impart knowledge, in a tone sufficiently sincere and chummy that we can buy him as a good teacher with a fine rapport with pupils, and the scene, although static in movement, has energy and rhythm. (Soon afterwards there is also a wonderful fleeting moment where Elliot seems to have a premonition of the disaster.)

The DVD/Blu-ray release contains several deleted scenes. The first one was supposed to open the film. It lasts almost five minutes and details an intense domestic quarrel earlier that morning that is only hinted at in later scenes. (The first four of the five deleted scenes can be seen on YouTube for the moment.) In his introduction Shyamalan explains that it “underlines the basis of their relationship”, but he decided that “we told you everything about the couple and it felt like there was no tension in the movie” and since “we find out every piece of this information along the way, why don’t we just take it out”. “The thing we shot was really back story” and its value was as “an incredible exercise for all of us and the actors to know where the characters were coming from”.

It is hard to agree with this. We have no inkling of how intense the fight actually was, with Alma throwing a figurine that almost hit Elliot in the head. Alma also seems to have no hope for their marriage due to their different personalities, but in the finished film everything appears to revolve around a silly episode where she was tempted to be unfaithful. With a lack of understanding about the depth of their problems, their later squabbles seem merely inconsequential, especially since the couple come across as so childish and the actors so unexceptional. So the tension that Shyamalan reaches for never materialises.

Besides being a fine scene in itself, hitting a truthful note of quiet intimacy unlike anything else in the story, it also establishes a few things that could have eased the confusion about character motivation that plagues the film and, as a satisfying whole, practically sinks it. As we shall se, there is later dialogue that specifically points back to that scene and, becoming unmoored, just piles more strangeness onto the film.

It also helpfully drives home the fact that Elliot is an immature character who cannot stop himself from joking: when Alma tries to have a serious talk about her emotions and the entire viability of their marriage, he produces a mood ring he has just found in a cereal box and wants her to try it on so they can see what she is “really” feeling. (This is why there is a mood ring on a table, from where Elliot snatches it when they evacuate – without the deleted scene our view of the ring is discoloured: we believe it is a cherished memento kept around since their first date.)

In the classroom his gentle ribbing of the disinterested pupil about his nose is fairly standard from a good teacher employing engaging metaphors. The following situation is eyebrow-raising though:

As the film is, we understand that it is a joke, but have no solid basis to ground it in – in the deleted scene, Alma says his childishness is key (“the reason you’re a good teacher, Elliot, is because you’re a kid; the kids relate to you that way”) – so it just appears mysteriously out of left field, not least because of the lameness of the joke and the strange way Wahlberg performs it. Might he be trying to ingratiate himself with the pupils by mocking authority? This is just the beginning of a pattern of hard-to-understand utterances and behaviour. (His use of “downright whack” towards the nose pupil only sounds strange though.)

After the heroes’ train has stopped in the middle of nowhere, he asks a bunch of conductors: “Filbert? Does anybody know where that is? Why are you giving me one useless piece of information at a time?” The last sentence is exceedingly strange, even as a joke. (If you think it might be established idiom, google the last eight words and all you get is a depressing list of people mocking this film.)

The “I am talking to a plastic plant” scene works better, also because he is trying out the nursery owner’s habit of talking to his own plants, so there is a context and motivation behind it. This is the only major comic turn in The Green Effect, carried over virtually unchanged, where it would probably have worked fine as intermittent comic relief among the otherwise pressure-cooker plot. In the film it has to contend with being just one curious, hard-to-determine incident among many. (In The Green Effect the nursery owner is not addressing his plants, so this is in fact an improvement in The Happening.)

One of the strangest incidents is Elliot’s monologue, shoehorned into the march across the fields to possible safety: “If we’re going to die, I want you to know something. I was in the pharmacy a while ago and there was a really good-looking pharmacist behind the counter. Really good-looking. And I went up and I asked her where the cough syrup was. I didn’t even have a cough. And I almost bought it. And I’m talking about a completely superfluous bottle of cough syrup. That’s like six bucks.” Alma inquires with an expression of complete bewilderment (shared by the majority of the viewers, one surmises): “Are you joking?” He confirms with a nod.

Here there is some irony because she feels relief that he is joking – the anecdote is a coded message of forgiveness for her recent confession about having flirted with being unfaithful – since in the deleted scene she complained he was joking too much, but this point is lost in the film. The problem here is that Wahlberg is delivering his lines and his nod with such a strange, disdainful expression, which might be meant as passive-aggressive. Anyway, it does not ring true that someone would behave like this in a life-or-death crisis, so this really has to be funny to be acceptable as “movie comic relief”, but it just comes across as supremely awkward. It is as if he cannot forgive her directly but must joke about it while simultaneously lording it over her, ensuring that she suffers a little first. She ends up being grateful for this treatment. Emotionally one of the weirdest moments of the film.

The most conspicuous example of Elliot’s near-pathological joking comes as the fugitives stand outside the barricaded house, desperate for some food, trying to convince those inside that it is not dangerous to let them in: “Nothing’s happened out here yet. I mean, you can see that. Just listen to our voices. We’re perfectly normal. (in an absolutely abnormal toneless, monotonous, falsetto voice he offers the following Doobie Brothers song) ‘Old black water, keep on rolling, Mississippi moon, won’t you keep on shining on me?’ See? We’re normal.” Here there are helpful, resigned sideward glances between Alma and Jess to underline he is joking – or do they simply agree that he is a terrible singer? In The Green Effect Elliot wanted to become a musician but seemed to have no talent – and it is truly pathological to hint that they are abnormal when they desperately need to appear as the opposite. Still, this incident comes across as reasonably funny if we understand his personality.

The problems with Elliot’s joking is legion: it does not happen often enough so we understand it is a compulsion, the delivery is at times so strange we have a problem placing it as a joke, and we lack the foundation from the deleted scene. In fact, it took me several viewings to understand that Elliot is a irrepressible joker: by way of elimination, it was eventually the only possible explanation (and it was nice to get it “confirmed” from that deleted scene).

It is nothing new to be uncertain whether situations are meant seriously or not, for example in films using a certain deadpan humour. On my first viewing of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (Wes Anderson, 2004) and even Shyamalan’s own Lady in the Water, I was at times bewildered whether some scenes were ironic or should be taken at face value, but it took only a second viewing to be dead certain they were humorous. With The Happening I have the feeling I will never get to the bottom of the matter (like the earthbender fight scene in The Last Airbender).

Later, Jared and Josh (Robert Bailey Jr. and Spencer Breslin), two precocious, obnoxious teenagers, join the heroes, Jared retorting when he hears the main couple have no children: “How come? You got a problem?” Later he offers: “You need to take personal responsibility for yourself in a relationship. That’ll make a difference.” Probably this is supposed to be irony, that a youngster pretending to be world-wise is interacting with an adult that is very childish, but it just feels forced and coming out of nowhere.

As so many other things during the first hour of The Happening, these characters can be mildly amusing, perhaps, on a first viewing, but have absolutely nothing to offer and, much worse, just detract from or maybe even help torpedo the experience upon repeated viewings. Often the quirky humour also has a confusing and alienating effect. With the vagueness described in the next chapter added in, the film has too many moving parts of strangeness, and the first article lamented the overload of the quirk-within-quirk-within-quirk structure.

IV: Vagueness and strange writing

Be aware that when people want to ridicule The Happening for its dialogue, lots of it are quoted out of context, perhaps as a result of having given up on the film, spending the rest watching it in bad faith, just looking for new sources of mirth. Some have complained about the first appearance of Elliot’s best friend Julian (John Leguizamo in an absolutely adequate performance) that it contains on-the-nose exposition because he is declaring he is a math teacher. But this is part of a longer speech about people being comforted by numbers, which might seem odd to emit as a first appearance. His character comes across as nervous and talkative, however, so the purpose of his chatter (plus setting up an important feature of the Princeton suicide scene) is to calm himself. Later, in the train station, he makes an odd-sounding mention of Cabbage Patch Dolls, but again he is trying to soothe his own nerves about a menacing situation by comparing the traumatic experience of getting the sought-after tickets to an innocent craze.

Another problem with the deleted opening scene is that almost right from the start, an unfortunate vagueness is introduced, a condition that only metastasises when nourished by the many instances of unfortunate turns of phrase as well as other oddities and inaccuracies. For example, in the early scene outside the school after teachers and pupils have been sent home:

- Julian says: “I’m going to tell you something you should never tell your best friend.” Elliot answers: “Why is everybody saying that?” In the deleted scene Alma tells Elliot: “I’m gonna tell you something that you should never tell your spouse.” Absent this, Elliot’s answer (simply pointing out the echo from earlier) makes him sound odder than he is – as viewers we ask ourselves: are people saying this a lot in today’s society, or is this Elliot making a very private joke? We can ask as much as we want, but we will never understand it from the current material in the film.

- Soon Julian says: “I saw her on your wedding day.” Elliot responds: “Again with the wedding. What?” Is Julian somehow obsessed with his best friend’s wedding? No, this is simply another reference to earlier, Alma’s “On our wedding day, when I walked down the aisle and I saw you waiting, I knew you weren’t the guy to make me feel safe to change the way I see things”.

- Julian goes on: “She’s never going to jump in when you need her, man.” This is yet another potential echo – to Alma’s “I just don’t believe in a big moment you’ll step up – you’re a kid” – providing a diametrically different view of the wedding: now it is not Elliot but Alma who is claimed to be not dependable in a crisis.

- There is also an ever-so-slight blip of oddity in the third act where Elliot says about the situation with the menacing Mrs. Jones: “Well, we need to stay in this house. You want me to protect you, this is how we have to do it.” This comes across as a sudden male chauvinist attitude but refers to Alma’s “You don’t protect yourself like an adult, and you don’t protect me.” (Also, without knowing that Alma wants out of the marriage, we perceive Mrs. Jones’s question “who’s chasing who” and Elliot declaring himself as the chaser, as merely a sweet moment, as well as coming a bit out of left field.)

- This is just a side effect: In the deleted scene Alma talks about their wedding day and walking down the aisle where Elliot was waiting. Without this we lose the underlying meaning of a wedding reenactment during the climax, when Elliot and Alma walk towards each other, with Elliot waiting for her and later stretching out his hand to her. Also the question of (lack of) commitment that springs from Alma’s doubts about her marriage can also be directly connected to Julian’s “don’t take her hand [in “marriage”] unless you mean it” when he leaves Jess in her care. (I am indebted to the colour theory for pointing this out.)

- Another side effect: Alma is very moved when she observes Elliot comforting Jess by the roadside, but lacking their initial conversation we do not grasp the full extent of the reason: this is precisely Elliot stepping up, proving to be a caring adult in a crisis, not a kid in an adult body.

- Yet another, more serious side effect: when Alma finds out she is pregnant in the first epilogue this seems simply like a confirmation of their regained normal life after the disaster, but in fact it is a milestone since we learn in the deleted scene that she does not want children because of her dark worldview and low esteem of Elliot.

- Some more parallels become weakened or invisible: Since nature in the film is punishing mankind for our bad deeds, it is interesting that Alma’s worldview is similar to that of nature, as well as being a milder form of Mrs. Jones’s extremely resentful attitude towards the outside world. (The latter is also pointed out by co-producer Jose Rodriguez in the Blu-ray extras, but the point is totally lost.)

But The Happening dialogue has no problem being odd all by itself. In the classroom discussing the vanishing bees, Elliot states: “But it’s all over the country. It’s a coordinated event in 24 states.” So it happens in the whole country but only in half of it, and only in those 24 states. He possibly means that it goes on in many states spread across the whole country, but it sounds strange that it could happen in one state and not at all in a neighbouring state, and how can this then be anywhere near a coordinated event?

In the same scene someone says: “Whatever this is, it looks like it’s not occurring about 90 miles from here.” Again very strange, specific phrasing. So this guy knows immediately how far it is exactly from here to there? He could be a local person of course but there are so many odd turns of phrase in the film that constantly call attention to themselves.

After Elliot and his small group have survived the wind out in the field, he says: “Nothing happened. It’s the size of the groups, I think.” He almost immediately follows up with “Could this really be happening?” This is rather clumsy since he just said something had not happened. He obviously refers to the whole suicide epidemic, but could he not have said something like “this is unreal” or “what a crazy situation”? Or maybe he is marvelling over the fact that he was right about his theory (my guess), is the point to get in as many references to the word “happening” as possible, is it intentionally “bad B-movie dialogue”, or is it a carelessness we are not used to from Shyamalan? It is hard to establish a consistent experience of a film that just comes across as totally, irreparably vague.

V: Alma and nebulous character motivation

Again, some of Alma’s odd behaviour throughout would have been more plausible with the deleted opening in place. It is not spelled out there either but she seems to suffer from catastrophic thinking, also known as magnification, a psychopathological condition of irrational clinging to worst-case scenarios (more about this here). This is a nifty character idea, of course, for a disaster movie.

In the deletion she confesses to several things related to this: (1) that the childish Elliot will not be able in a big moment to step up, something she suddenly realised when spotting him waiting for her as she walked down the aisle at their wedding; (2) “suppose we had a child and something went wrong, what if its lungs failed, I don’t know, something bad, how would you handle it”; and (3) “I’m turning into a monster, soon you’ll find several body parts of strangers in the freezer, Elliot, this is how it starts”. And her later remark, “I look like Frankenstein”, also introduces her penchant for references to popular culture, often used erroneously. The scene also establishes the core reason for why she seems petrified at the thought of taking responsibility for Julian’s daughter, Jess. (We also learn she is a therapist – I’m not really queuing up for an appointment! – although in the “official” film her occupation is unknown.)

Alma’s pitch-dark worldview is likely a direct product of this catastrophising. As the film stands now, this darkness only seeps out via mysterious remarks that only make her sound whiny and immature. In the deleted opening, however, she emphatically deems all of humanity to be “crap” (“The reason I’m scared to have kids, Elliot, is all I see when I look at the world is crap. How am I supposed to bring a kid into the world feeling like that. I knew when I met the right guy he would make me feel safe to have that kid – he would change the way I see things.”). She has concluded that she and Elliot are incompatible because he is an optimist and she a realist. (Her blinkered worldview speaking again, because she is definitely a pessimist.)

Alma’s outlook is validated in a remarkable, daring moment afterwards – in its vulgarity it is almost as shocking as the suicide scenes – when she has left the house and seems to stand for a moment trying to enjoy the peace and quiet:

So this is the reason for her odd remark in her first scene, watching the news: “it makes you kill yourself; just when you thought there couldn’t be any more evil that could be invented” – again an extraordinarily clumsy sentence –

Still her character behaves rather inconsistently. Sometimes she seems quite relaxed, not like strained composure faced with threatening disaster. For example, when Julian bids farewell before going to Princeton it is more like Deschanel just stands there without acting (or does her character not understand that Julian is likely embarking upon a suicide mission?). Suddenly, however, she bursts out with nervous remarks when during their car ride they discover figures in the road: “It’s bodies, isn’t it? I knew it would be bodies. How could it not be bodies?” One suspects that the rambling nature and tenor of this outburst, again, spring from her worst-scenario thinking.

The result of the vagueness is that the characterisation of Alma comes across as borderline sexist. Very often she seems stupid (not unusual for female characters in B-movies, so it could be intentional). She is an expert on pointing out the obvious:

Following this, after everyone has on myriad occasions pointed out the same, she opines: “Whatever it is, terrorists, a nuclear leak, plants, it’s probably safe to get away from people right now.” (This attitude could also be explained by the fact that she generally wants to get away from people, because of their inherent crappiness.)

Her stare in her opening image, plus the staring in scenes where she is supposed to be overcome by emotion seems overdone, somewhere between unhinged and hysterical.

When Koresky writes that Deschanel is “reduced to a series of inexplicable, flighty mannerisms”, as indicated above, often they can be explained but the deleted scene is very helpful. Obviously, starting with a five-minute domestic fight or some terrifying suicide scenes are two vastly different kick-offs. I much prefer the punch-in-the-gut suicidal beginning, but we are left with an unresolvable structural problem, since as we have seen so often, without the fight the heroes’ motivations, personalities and at times dialogue are too hard to understand. (With all the dubiously executed quirkiness and humour, however, I doubt that the deleted scene could have magically straightened out the whole film.)

There is also a central imbalance, which Koresky is pointing out: “As feeble as Wahlberg and Deschanel are, Shyamalan still puts their marriage front and center, even amidst the outrageously gory deaths happening all around them, positing Alma’s possible infidelity as a narrative thread of equal fascination to plant-induced mass suicides.” (The deleted scene trips up the film again, their problems were meant to be much deeper.) It is not unusual, of course, to have a personal conflict running parallel to a big external one, and here there is thematic justification, but it is seldom to see the former come across as so anemic and inconsequential as in The Happening.

Strange as it may seem after all this criticism, from the vantage point of its staying power across repeat viewings, the shortcomings of the film’s first hour do not really make it unwatchable. In addition to the accidental entertainment value arising out of the awkwardness, there are always sharp suicide scenes, flare-ups of sense-of-wonder beauty (like here and here), and Ashley Sanchez moments to tide us over. Eventually, however, there comes a period that is a bit of a slog and threatening to break the whole enterprise.

The fallow period starts as the heroes meet up with other parties, including the tiresome Private Auster, at a rural intersection after about 37 minutes and lasts until about 58:30 with the arrival at the barricaded house. Until then there has at least been a pleasing energy to the proceedings as the heroes are moving about fleeing the threat. At the crossroads things get very static, however, the multiple discussions and crowd scenes have no lasting fascination, the suicide scene by phone is disappointing, the sequence out into the field is abysmal, large chunks of the model home scene are devoted to conversation, exposition and science lectures (it ends with a 67-second take, the film’s third longest, but it feels artistically flat), there is the walk by the fence conversing with the obnoxious youths, and the pharmacy anecdote. During this period, little else than this wonderful moment by the roadside, the talking-to-a-plant sketch and the lawnmower suicide has any interest.

We have to take a (masochistic) look back at the film’s nadir, however, as the fugitives take to the fields at around 44 minutes…

… and the next four minutes until there comes some movement and at least nominal excitement, with this swooping camera movement down at the protagonists as they are overtaken by the wind.

Not only does this passage contain the most uncomposed images of the whole film, but the suicide scene involving Private Auster’s group is prosaically staged and his departing words – “My firearm is my friend! It will not leave my side!” – is more comical than the lightly absurd, slightly gun-culture-critical comment it is probably meant to be. (The Green Effect simply lets him say: “Yes sir sergeant! Yes sir!”) Even worse is the situation on the other side of the small slope, where shots are ringing out as the members of the first, unseen group are killing themselves. This seems to be intended as a tragic and unbearably suspenseful scene as Elliot has to figure out – fast! – how to save his own group from imminent death, while the others are in hysteria and constantly disturbing his half-panicked train of thought. This less than ideal environment for problem-solving is possibly meant as absurd, black humour in the middle of the tragedy.

In line with her crappy view of people, Alma is whining, in her usual rambling way when her anxiety goes into overdrive: “We can’t just stand here as uninvolved observers!” and “We are not going to be one of those assholes on the news who watches a crime happen and not do something! We’re not assholes!” But her childish tone and vulgar language, soon echoed by Elliot’s “All right, be scientific, douchebag” – according to the IMDb trivia an improvised line – combined with an extreme close-up of Wahlberg, for 18 seconds indelicately pushed right up at his nose, totally misses the goal of creating suspense and urgency. (I must admit to some perverse entertainment value out of all this though.)

It would be tempting to fuse the well-crafted barricaded house scene with the third act as a long stretch of excellence – although it takes a momentary nosedive as Wahlberg’s crying at the end is extremely unconvincing – had it not been for the fact that the following three vignettes, showing people panicking/preparing even though they live far from the outbreak zone, are afflicted with the same oddly unimaginative approach as earlier. The glimpse of the rough militiamen has a certain charm and satirical precision though.

VII: An estrangement device?

As regards all the weird talk and behaviour in The Happening, this has been suggested to be a device to make it constantly uncertain whether someone has been infected, so that people might start killing themselves at any time. It is hard to buy this: infection is signalled in the film by a specific pattern of repetitive talk, people standing still or walking backwards. (I can offer the joke, though, that maybe the inexpressive Wahlberg has been cast because one could constantly fear that his stiff acting means he has been infected.) Also, none of the characters express any fear that odd behaviour from their fellow travellers might be a sign of imminent danger. (Compare with Breck Eisner‘s excellent Romero remake The Crazies from 2010, where characters are constantly eyeing each other for tell-tale signs of irrational behaviour.)

Many have been reaching for terms that can encompass the full extent of the weirdness, however: In the Facebook thread, Jonathan Hastings noted with interest “the way that Wahlberg and Deschanel appear like they are giving performances under the influence of some kind of hypnosis and/or mind-altering substance”. Mike Thorn mentions the hero’s “wide-eyed, dopey childishness” played “as a man continually out of sync with his time and surroundings; his off-kilter line delivery falls somewhere between the otherworldly inhabitants of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks and the kind of doe-eyed character one might expect James Stewart to play in a Frank Capra film.” He suggests that Shyamalan is “inciting performances that recall B-movie overreaction, both comical and uncanny in their weirdness.”

In his review, Richard Harland Smith says that the film is “full of scenes that are – even given the inexplicable events – just plain odd. Odd line readings, odd character motivation, odd writing, and these eccentricities distance viewers from the material as early as the first scene.” In the commentary field he explains that he found the film “to be all knees and elbows – I spent most of the film with my head cocked at a dog’s angle – but I wound up thinking about parts of it long after it was over, which is more than I can say for a lot of modern horror movies, even the ones I like a lot.” He concludes: “Maybe we’re missing the point. Maybe the dialogue does what it needs to do, takes us where we need to go, and and our discomfort with it means, ultimately, that the fault lies not in the stars, but in ourselves.”

Possibly all the off-the-wall behaviour can be said to be an alienation device to underline the treacherous world the characters have suddenly been plunged into, but it has never worked that way for this viewer – although while compiling this article with its avalanche of oddities one can start to wonder whether The Happening is some kind of sublime masterpiece of absurdity and estrangement.

Craig Lines’s impassioned defence

And perhaps it is? A far more positive attitude that I have been able to muster for the film as a whole can be seen in this article, maintaining that The Happening was fatally misunderstood, by the writer Craig Lines, a very personal take which is by far the most interesting and engaging piece on the film I have seen.

He states it is “undeniably creepy” and that “even many of its detractors admit that the suicide scenes unnerve them.” He points out that “it’s the randomness – the unfathomable juxtaposition of this self-inflicted horror onto normal, everyday life – that’s shocking and therein lies the crux of The Happening.”

“It’s a sister piece to Shyamalan’s own Signs, in which everything happened for a reason. Even the most trivial event tied together at the end of Signs to demonstrate the workings of an omnipotent greater force. If Signs was an overtly religious film stating without doubt that there is indeed a God, The Happening is the opposite; a spiritual plea for help – a desperate crisis of faith.”

This is particularly insightful: “The text, when you boil it down, is about a man (quite literally) running away from the seemingly inescapable impulse to kill himself.” (I touched upon something similar in the first article: “On a metaphorical level, however, the film offers an utterly bleak pronouncement about mankind’s state of mind: when the urge to self-preservation is removed, their first impulse is to kill themselves.”) The author continues: “He becomes increasingly abstracted from the world as the film goes on and the pressure increases to take charge of his life. It’s a clear metaphor for the ever-creeping shadow of depression; the frustration of knowing what to do in theory but being unable to bring order to the chaos of the mind.”

In the scene in the field, “they scream out for him to bring order into the chaos” and the hero “yells ‘Give me a Goddamn second!’ and tries to apply science to the situation as half of the party he’s with start to kill themselves is fraught with the pain of a man who can’t cope, who can’t rationally apply order to anything, yet is terrified by the threat of chaos taking control.” (One can retort, without invalidating the overall argument, that at least here he could cope: he successfully applied his science training and figured out they had to split into smaller groups.)

I agree with much that Lines says about the third act, especially the poignancy of the climax, and some suicide scenes. But “we learn within the first act that the toxin making people kill themselves is being generated by the trees” is simplifying things a bit because enough other explanations are offered to create ambiguity, as discussed here. And is “instead of having to reach the city to find denser populations” they shrink back into rural areas, such a disaster movie trope inversion? For example, in the above-mentioned War of the Worlds people flee the cities, and there are surely many films and books where cities are attacked or become untenable. Reaching isolated spots here means safety, like in John Christopher‘s famous 1956 novel “The Death of Grass“.

One can also agree with what he says about the purposefully irrational characterisations but as I experience the film, the intellectual conception does not translate into a satisfying execution – quite a few situations end up being more infuriating and overdone than a stimulating portrait of chaos.

The soulful Ashlyn Sanchez

After all the grief about the lead actors, one cannot complain about Ashlyn Sanchez, however – her role is not that central and demanding, but she plays Jess to perfection in everything she is asked to do. Shyamalan thus continues his unfailing rapport with child actors. In the second article we have already seen her in two memorable moments outside the barricaded house (here and here).

*

In addition to some flashes here and there in The Happening, many of the grim suicide scenes are fine to excellent: the two park events, the Princeton drama, the construction site, as well as the barricaded house scene whose violence makes it fit in here. And the last third, while not as formally adventurous as his previous work, is very good: resonant, precise, structurally interesting and tonally consistent, and, perhaps tellingly, it preserves the serious tone of the original script. These good segments take up approximately 35 and half minute of the 91-minute film.

For a Shyamalan enthusiast, however, it is heartening to conclude that the relative artistic failure of the three films of his “middle period” – I say relative, since the last half of The Last Airbender (2010) is excellent, with its formal rigour, aesthetical allure, and monumental climax; the last hour of After Earth (2013) is a lyrical journey of visual beauty – has occurred in a situation of diminished artistic freedom. As he said himself in this post-Glass, april 2019 lecture, ” I felt really lost. It just didn’t work. … After this 10-year period of working at studios on junk movies, I was not happy.”

He had to remove roughly a half-hour from The Last Airbender as part of a studio-imposed decision to post-convert it to 3D, as a cost-cutting measure. On After Earth he was a work-for-hire director for its star Will Smith, who was responsible for directing his son’s acting in the lead role, and its thin, flat early parts on the foreign planet were rumoured to have been severely cut. (See here for a further discussion of these two “companion films”.) The original Green Effect vision for The Happening was very serious but for it to be more palatable for Fox, humour was added to detrimental effect, although Shyamalan is of course, as still writer-director, to blame for not nailing it.

Remove these three films, have a look at M. Night Shyamalan‘s filmography from 1999 to 2019 when he is left to his own devices, and behold a string of unbroken excellence.

*

Addendum: The Green Effect

The most important differences are, seen from the point of view of The Green Effect (the script can be easily found online):

- The Green Effect is wholly unambiguous about the nature of the threat against mankind, so there is no frantic speculation along the way about its causes; early on, during the Filbert diner scene, government warnings communicate that plants have risen against mankind

- the suicide events are not confined to the Northeast US but occur world-wide, and in many places simultaneously, right from the start (but still eventually attacking increasingly smaller populations)

- the heroes’ action in the climax, walking straight out into the danger zone outside Mr. Jones’s house, is the result of careful reasoning, not an act of desperation, confusion and instinct as in the film (on this point I vastly prefer the film’s more poetic denouement) – and when Elliot walks out, Alma waits inside in the springhouse until ascertaining he is safe; in the much more reciprocal version in The Happening it is entirely uncertain whether nature could still attack when both are out there

- the mood ring and its role during their first date only come up during the speaking tube conversation – it is never a prop in the story – and here Elliot eventually does remember the colour of love: green, thus the name of the script, and their discussion leads him to understand that nature acts like a vast mood ring, gauging humans’ emotions via the biochemical energy they emit; then he realises that to cease being perceived as a threat to (green) plants, they must embrace true love and give up destructive behaviour against nature – so when they go outside to meet, they reenact their wedding day, with her walking up the aisle and him already waiting, but this time with full commitment

- the end is very dark but still hopeful: it seems most of Earth’s population has succumbed, only those who have embraced love in various spots throughout the world have survived (so no epilogues with a return to the city and in Paris)

- there is no humour, other than the “I’m talking to a plant” scene, a comic relief breathing space that almost any suspense story will have, and a little standard smiles-through-tears dialogue during the climax

- there is no compulsive joking or peculiar speech patterns from Elliot, no pathological catastrophic thinking from Alma, both are completely normal – although Elliot has a problem facing reality – and thus no odd or humorous behaviour from them, neither from any supporting character, who are otherwise all carried over The Happening (and the “crappy” behaviour, like people not wanting to give out-of-towners a ride in Filbert, does not exist)

- the script includes the opening marital fight that was cut from The Happening, including the throwing of the figurine, but here Alma’s unfaithfulness has been more serious and she determined to leave him, and discussions of their marital problems intrude on the later action only in brief moments

- the speaking tube conversation brings closure to Alma’s desire throughout the film to have a clearing-the-air talk about their relationship

- while being a teacher here too, Elliot would like to be musician; instead of a mood ring he drags a guitar with him all the time, and instead of using the ring to soothe Jess in the diner he plays a song for her*

- the action goes over two days instead of one: after having survived the attack in the field, they sleep out in the wild, and it is not until the next morning they arrive at the Model Home and the development site (the staging of The Happening is smarter, gradually revealing that everything is fake in the house they move around in)

- the scene with the barricaded house is new for The Happening; instead in The Green Effect they arrive at a big farm where everyone has committed suicide on a table saw (and a little girl who has been tied up to save her promptly kills herself when released), and in this version too Josh and Jared die, but here killed by plants after they stay behind at the farm trying to burn the surrounding vegetation in order to stay permanently at the place (they are still anti-social and vaguely threatening, but not obnoxious or precocious)

- suicide scenes: not in the film: at the New Jersey Turnpike between Elliot leaving school and arriving home; in Holcomb, where the heroes soon come across bodies in the road (its lawnmower suicide appears elsewhere in the film, also see Mrs. Jones below); a woman who has stayed behind at the crossroads near the field suffocates herself with a plastic bag; at the model home five bodies are discovered at a nearby construction site and the heroes play a recording of an interrupted TV broadcast that seems to lead to a suicide in the studio; only in the film: the Philadelphia Zoo video (the suicide event at the music recital relegated to a deleted scene exists in The Green Effect, placed after Elliot and Alma leave their house)

- Mrs. Jones shows no explosive paranoia in the evening or morning, there is no deformed doll, nor does she smack Jess’s hand at the table; she is still reserved, isolated and very religious though (she commits suicide by stabbing herself in the chest with a cross) – the role has probably been fleshed out in the film to make better use of the very accomplished Betty Buckley – and her banging her head against the wall and crashing it through the window in The Happening are a combination of the Holcomb and New Jersey turnpike scenes, see above

- it has a silly turn of events at the end though: in The Green Effect she simply succumbs outside but it turns out she is not entirely dead, and when she appears behind the couple standing outside having their communion with nature, they have to run and hide in the springhouse to avoid getting caught up in nature’s renewed attack on Mrs. Jones (thank God that was not in the film)

- the classroom scene is much shorter, and plot trajectory foreshadowing is changed: instead of the extensive discussion of bees disappearing and guesses about reasons, Elliot is showing pictures of French cave paintings, making a point that cave people worshipped nature and lamenting the fact that some paintings had been vandalised by thoughtless human beings

- early on, Elliot recognises characteristics of the suicide events from an earlier student paper, which he takes with him before they evacuate, and which later provides some of the scientific background about hostile plant behaviour

*) Much fun has been made of the fact that Shyamalan supposedly wrote the film especially with Mark Wahlberg in mind, as if he would be ideal as a teacher. But could the character’s ambition to be a musician in the original script and Wahlberg’s background as a rap performer, as Marky Mark, be the real reason? Is his bad singing outside the barricaded house an in-joke reference to his past career? This could also explain his use of “downright whack” in the classroom scene:”whack” as an adjective is prevalent in rap music, still used but especially in the late 1980s and through the 1990s when Marky Mark was active. The expression is of course also meant to show Elliot’s ability to connect with pupils.