M. Night Shyamalan’s The Visit, Part II: Shit happens, but with precision

The author is behind an analysis project about M. Night Shyamalan‘s films. There are several articles on each: The Sixth Sense (1999, here, here and here), Unbreakable (2000, here, here and here), Signs (2002, here, here, here and here), The Village (2004, here, here and here), Lady in the Water (2006, here and here), The Happening (2008, here, here and here), The Last Airbender (2010, here and here), After Earth (2013, here and here), Split (2016, here, here, here, and here), Glass (2019, here), Old (2021, here). This is the second article on The Visit (2015), the first one is here. All the articles can also be accessed through this overview.

*

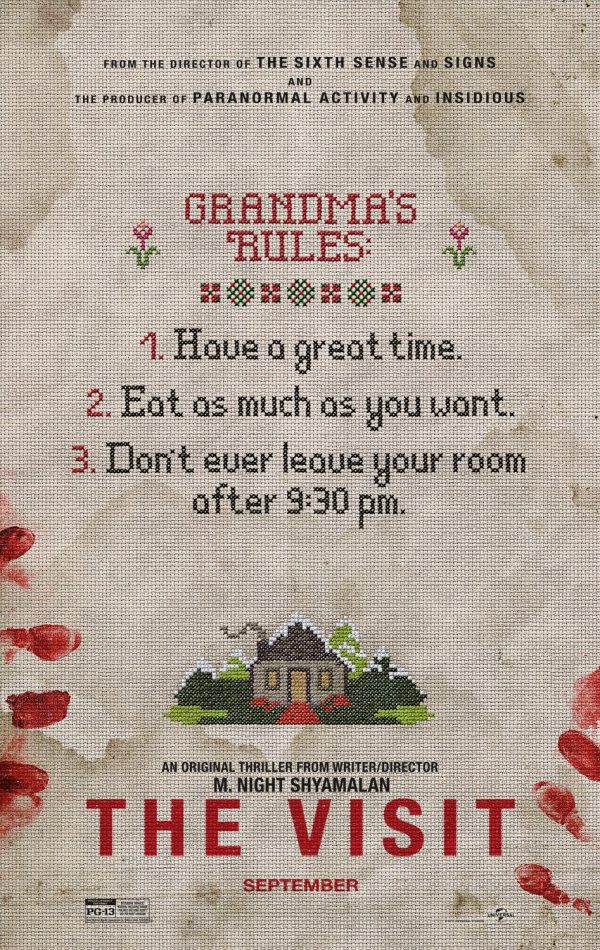

This second article on The Visit (2015), M. Night Shyamalan‘s most audacious film, will look at how it is dealing with and commenting upon the various challenges, conceits and conventions of the found footage genre, how it is sneaking in artificial elements of a sometimes highly technical nature, and its various techniques and consistency. Finally, it will round up a range of references and connections to the rest of his oeuvre and a few other films. (The first article is here.)

The Visit revolves around a week-long trip by 15-year-old Becca (Olivia DeJonge) and 13-year-old Tyler (Ed Oxenbould) to their aged grandparents, affectionately called Nana (Deanna Dunagan) and Pop Pop (Peter McRobbie). The siblings have never met them before, due to a violent, irreparable rift with the children’s mother (Kathryn Hahn) fifteen years ago. The location is a remote farm, with no cellphone coverage, and Becca is determined to film as much as she can for a documentary, hoping for the visit to become a bridge to a broad family reconciliation.

I: The found footage conceit

Capping off a film of wild mood swings, there is a delightful collision between the seriousness and warmth of Becca’s last interview with her mother and Tyler’s hilarious rap performance during the end titles, which radiates a liberating “it’s only a movie” feeling, his lyrics retelling the children’s adventures in wonderfully irreverent fashion. The mood is now so light that the film becomes ambiguous – has what we have witnessed in The Visit been some kind of mockumentary? After all, these young teenagers have been in mortal danger, and Nana (and maybe Pop Pop too) was killed by one of them in a ferocious close-quarters struggle. As for their mother, she seems rather too calm and unscathed by a tragedy that could easily have resulted in her children’s death, not to speak of the news that both her parents have been murdered. Even after having been incommunicado for 15 years, it should still be a shock.

The fact that we now see Becca use a mirror, lovingly doing her make-up and brushing her hair, might indicate that she overcame her fear of them in the showdown with Nana – or that she was never afraid of them in the first place. The latter interpretation is encouraged by the credits rolling by, including the names of the actors, driving home the status of The Visit as a work of fiction.

The Visit is often, rather thoughtlessly, placed in the found footage genre. (This is an interesting article discussing it as such.) As long as all the footage was intended for Becca’s documentary right from the start, and especially since she is presented as highly dedicated and film-theoretically schooled, the film’s polished look and relatively artful organisation should not prevent it from being a found footage movie. Similar to Werner Herzog‘s documentary Grizzly Man (2005), someone else could have come across the footage, and in this case fulfilled the original maker’s intentions. (Becca is seen editing the film during the stay, so some of the work could already have been finished.) Thus, as for our immediate viewing experience and its believability, the fact that the film exists in a finished state does not necessarily mean that Becca and Tyler survived, so the suspense should not be ruined.

In this part of the genre landscape, there are quite a few categories to choose from: pseudo-documentary, mockumentary or the regular found footage type. (This article discusses The Visit and other “accidental” horror movies.) If it is a pseudo-documentary, ought we not, for example, to see the pretend-grandparents being alive, or the story at least having a clear resolution, rather than the ambiguous rap scene? There seems to be no established rule. Dadetown (Russ Hexter, 1995) reveals during the end titles that all of the supposedly real characters of the riveting true story were in fact played by actors. The Bay (Barry Levinson, 2012) uses a scrupulously documentary approach, editing together existing footage, for its horror story of the devastation of a whole town and does not reveal it as fiction like the other film, but instead indirectly lets on that it is made-up through the scroll of end credits. One could call The Bay a found footage movie too, perhaps, although the collection of material from a wide variety of sources would be unusual for that genre.

Precisely the credits question could be key. Super-low-budget found footage films like The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick & Eduardo Sánchez, 1999) and Paranormal Activity (Oren Peli, 2007) do not have credits at all, and more professional films, where actors and crew would demand it, usually saves it all up for the end credits, so no tell-tale indication is given the audience at the start about the made-up nature of what they are about to see. The Borderlands (Elliot Goldner, 2013), for example, has no opening credits, only the film’s title, and lets more than twenty seconds pass from the last shot until the credits start appearing. As for pseudo-documentaries and mockumentaries, respectively The Bay and the famous This Is Spinal Tap (Rob Reiner, 1984) have no opening credits either.

The Visit, however, does not care. Like any other feature film, names of actors and most important technical functions appear over three early scenes (in the car, at the railway station and on the train). Also, many movies nowadays skip opening credits, a fact that only underlines Shyamalan’s decision to be up-front about the made-up nature of his film. A counter-argument could be that coming into a genre that traditionally has been a low-budget entry point for unknown filmmakers as a firmly established director himself – hardly anyone else has attempted it than George A. Romero, although a more marginal figure in commercial terms, with Diary of the Dead (2008, no opening credits!) – there would be no use to try hiding the fact that this is a fiction film. The general cinema-goer will be less susceptible to matters of name recognition, however.

On the whole, perhaps it is more productive to look at The Visit as an exercise, adopting a set of restraints known from the above genres to set a creative challenge. This is a strategy often mentioned by Shyamalan – “I like limitations” – along the lines of how Hitchcock wanted Rope (1948) never to leave the apartment and shoot it to appear as one long take.

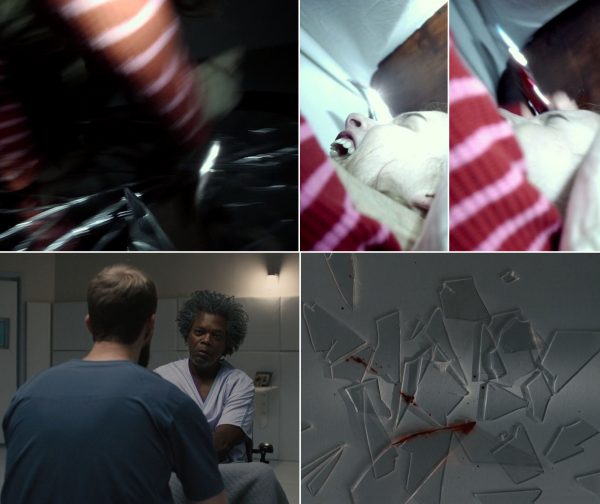

It is also tempting to look upon the film as a comment upon the conceits and conventions of especially the found footage film, including its fundamentally hilarious contrivances that people keep on filming even in desperately fraught situations and that cameras just happen to capture so much useful material. Perhaps the most satiric comment on the artificiality of those genres is the scene towards the end when the distraught kids are fleeing the house but doggedly still carrying their cameras, which ought to be dangling about and pointing all over the place, but nevertheless manage to catch everything that needs to be captured. (It does not hurt either for a low-budget production like The Visit that expectations for the technical level and the scope of the film will be adjusted to what a 15-year-old could achieve.)

So the challenge here would be that every shot must be explainable as being recorded by Becca and Tyler wielding their cameras, and in that department it is close to flawless, not surprisingly given Shyamalan’s utterly meticulous approach to filmmaking. Aside from that, The Visit is simply a fiction film about a 15-year-old girl attempting to make a documentary, inviting us to suspend our disbelief in the same manner as in a story about a bank heist or a weatherman getting caught in a time loop. If this author would be forced at gun-point to ascribe a genre, however, pseudo-documentary seems more fitting than mockumentary, since the latter is usually connected to satire, in a social context.

A special characteristic for the above genres is that persons so often are addressing the camera, looking directly into it, when doing narrating or explanatory segments, a visual rhetoric that helps convince the audience that what they see is real, and a strategy totally at odds with regular fiction films where everyone pretends the camera is not present. It will also be an abundance of moving point-of-view shots, or rather subjective camera since the need to maintain the illusion that everything is simply filmed by the moving character holding a camera will prevent any occurrences of the classical Hitchcock mode of alternating a POV shot with a shot of the character doing the looking, like famously and hypnotically done in Psycho (1960):

The restraints are also encouraging long takes – with just one camera in most situations, the only analytical “editing” would have to be via cumbersome, attention-grabbing zooms – and thus the average shot length of The Visit suddenly rivals Shyamalan’s early period: its ASL of 16.26 seconds puts it in second place, after Unbreakable and before The Village. (Here is a complete list of shots that last 30 seconds or more.)

The Visit seems at times a satire, or at least a comment, on the ingredients of the found footage genre. Contrary to most of those films, striving for a dirty, random, often highly-unstable-camera look to suggest spontaneous, wholly unplanned footage, Shyamalan’s take on it is a beautiful film, especially considering that it is ostensibly made by a 15-year-old, however conscientious and talented. (The old footage from her earlier childhood looks more “found”.) The framings are generally steady and, with the exception of the chase during the hide-and-seek beneath the house, without “shaky-cam”. Further stability is provided by the quite a few stationary shots when the camera is put down on tables and floors.

Steps are often taken, however, to at least give a nod to the fact that the film is shot by handheld cameras by inexperienced operators, for example Tyler’s brutal zooming when he starts using his camera, and despite its generally polished, sleek feel, it does not give off a Steadicam feeling either. The generally polished look suits the concept of the film, however: in line with all the deception and pretense in the story, The Visit is a work that only pretends to be a found footage movie.

The Visit can also be said to comment on the artifice of the found footage genres through the fact that the children continue filming even in the most desperate of circumstances. This is so prevalent in this type of film, however, that it must be deemed a genre convention. Figuring into this for The Visit is also the fact that the footage might be used as evidence in a future trial or as proof even if they are killed, like the message that Becca puts on tape as soon as she finds the dead bodies in the basement. On the other hand, it seems a futile hope since the footage could easily be erased by the perpetrators, or in the case of the technologically non-savvy elders, the equipment might simply be destroyed.

Artifice and polish

One thing is certain: for a found footage film The Visit does not shy away from nice artistic and technical touches.

This scene outside the house is masterful, exuberant yet solemn, filmed in a seemingly random way but comes across as very artificial and artistic. It takes the apparatus and framework of the found footage movie and transforms it into something else. The sense of artifice here is further elevated by the “rule-breaking” use of non-diegetic music, and a very odd one at that, discussed here. Scored music is seldom used in found footage films because it would undermine the idea of presenting the footage as unadorned.

The Visit also contains quite a few technical flourishes:

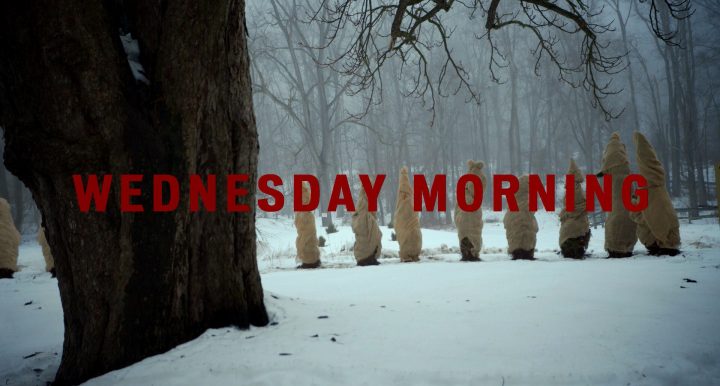

In addition to the above dissolves, there are other atmospheric shots of landscapes sprinkled throughout the film, often along with the “morning” chapter titles. Variations of the full moon appearing through naked trees are a favourite subject (although the fact that it seems to last from Monday to Friday is artistic licence and another subtle proof of the artificial nature of filmmaking).

The following slide show collects all of these shots:

The final moon shot also functions as a time-has-passed marker before the board game starts, with an added special foreboding since it is precisely the kind of night exterior shot the kids were prevented from going out to take, when Pop Pop closed the door on them. The late evening shot of the tree with the swing ominously creaking is another brilliant shot that Friday, in itself but also since it encourages a comparison to the carefree mood on the day the kids arrived. It is also notable that Friday morning is announced with a shot of hooks and sharp tools.

The end title sequence is an aesthetic pleasure and a mystical riddle in itself. Exactly when the music switches from hip hop to Tchaikovsky, places from the film are conjured up with ghostly magic, dissolving into each other, unveiled and veiled again, in a complex pattern floating from one side of the image to the other, always shrouded in the Tuesday morning fog, until we end up with the timber from early Friday morning, with the tree swing in the background. That image lingers for a while until it too, as if with regretful implacability, is gradually blacked out.

Tyler’s surreptitious, slow zoom-in on Becca during her emotionally fraught interview also comes across as artistic, in the way her face ends up half-banished from the frame, marginalised, and the emptiness in the composition, the road behind her, is allowed to loom much larger. It is as if the cold mechanics of the change of focal length is determining the artistic outcome, in a simultaneously studied and expressive manoeuvre:

As regards sound, the thunder on the last evening, which signals the pouring rain as the children later escape the house, is used to fine effect. Each time Nana appears behind Becca when they are shut in together is accompanied by a crack of thunder, and especially impactful is the sound, which here seems processed to make it more reverberating, when Pop Pop suddenly turns up around the corner with the dice for the board game.

Furthermore, The Visit employs a wholly artificial, but established cinematic trope for dramatic effect, using audio to conjure up smell: Tyler’s sight of the used diapers in the shed is accompanied by the sound of flies. As discussed in the first article, this could also be a natural occurrence, due to the warmer weather, which would also account for the thunder. The aforementioned visual distortions caused by rain is definitely a deliberately intended effect, so good thinking by Becca/Shyamalan to prepare us for it by inserting some thunder…!

Another established trope is exaggerated sound, namely the ominous creaking when the kids spot Stacey, the young woman who came by earlier, hanging dead from a tree; the sound would hardly be audible from a distance. More artificiality: Tyler’s voice is given an echo as he shouts for Becca after Nana has struck her yahtzee, and there is a ghostly sound over an exterior shot on Wednesday night before Nana’s sundowning. Also naturally occurring sounds are excellently used: somewhere, very discreetly, a church bell is ominously tolling while the kids run up from the platform for their first greeting with the “grandparents”, and there are crows in the background when they examine the footage of Nana’s interview.

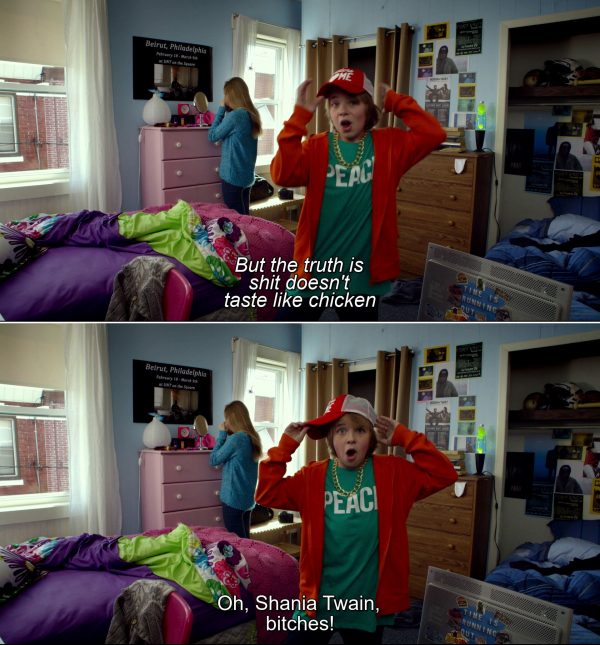

There are also a number of foreshadowings and/or instances of structural or formal irony, revealing the planned nature of the film, the very opposite of the randomness of a found footage movie. Tyler’s performance over the end titles means that Becca has granted his request that “maybe I can rap at the end of your documentary” – she is announcing this on a terse text card before the rap – and his last words, “Shania Twain, bitches”, not only celebrates the film’s delightful running gag of substituting swearing with the names of female pop singers, but he also fulfils her misgiving on the train that “right, because that’s how all Oscar-winning documentaries end – with songs of misogyny”.

Becca says: “I’ve decided to use Mom’s favorite musical soundtrack. It’s so over the top, it’ll be her presence in the documentary. Counter-point to the quiet drama. This’ll be ironic scoring.” But the irony is that she never could have expected to include such drama as the ferocious climax, so when it plays over the kids fleeing the house in the rain, it ends up being oddly appropriate and unironic, and what was intended as a kind-of-condescension towards Mom is now some sort of celebration of her. At the same time, the heightened drama of that music represents the essence of her flamboyant character, and it helps to further lift up the already overblown drama of this sequence.

At one point Becca says: “Old footage of us as kids. I was thinking of using it in the doc. I refuse to use anything that has my dad in it. That would mean I forgive him.” But at the end of The Visit it turns out she has given these clips a central place in a sequence expressing the healing of the whole family. The piano music over Mom’s second interview is yet another element she earlier swore to avoid: when Tyler points out that the footage of Becca and Nana holding hands makes him want to cry, she retorts: “Are you consciously aware that that’s my intention? I hate sappy movies. I find them torturous.” The irony here is that she learns that what she deemed cliches and too-obvious, in fact might be appropriate in highly emotional and dramatic situations. Now that she has lived through these types of events, she has evolved into a different view on what can be judged a cliché, and that her former attitude was purely intellectual. She has never experienced really strong emotions so when encountering them in movies, through music for example, she, an immature viewer, regards such devices as superficial and manipulative. And the scene where she embraces Mom is precisely “sappy”.

Finally, the already discussed horror scenes during the hide-and-seek under the house and in Nana’s bedroom during the climax are examples of the visual tension that Becca earlier explained to Tyler.

Camera techniques

These are the four camera sources in The Visit:

- two handheld cameras operated by Becca and Tyler

- the camera on the children’s laptop, which is crucial in a key scene

- the mother’s laptop, used from home and on the cruise

Below are some typical ways that the action is captured, and the methods/contrivances involved. In many cases, the camera is in the right place by magical coincidence, or after superhumanly quick and professional calls by the children as putting down the camera in the right direction.

Camera consistency

There is nothing new with the use of multiple cameras covering a scene in found footage films. In for example The Borderlands, investigators from the Vatican trying to verify a miraculous event are instructed to always have cameras mounted on them so not the tiniest detail will escape them. In The Visit there is almost obsessive attention so that shots in two-camera scenes shall fit seamlessly together, and in handheld scenes the camera movements from capturing one thing to another are very often shown. There is never unseen help from the crew, and all adjustments of cameras put in fixed positions are always seen. In fact, the handling of the cameras is almost as important than the story.

There are a few (possible) tiny inconsistencies which are detailed in this enclosure.

II: References

Here is a list of the film’s common themes and motifs with other Shymalalan works. The occurrences of mental illness in other Shyamalan films have already been discussed here, and its self-reflexive nature as related to his other films here.

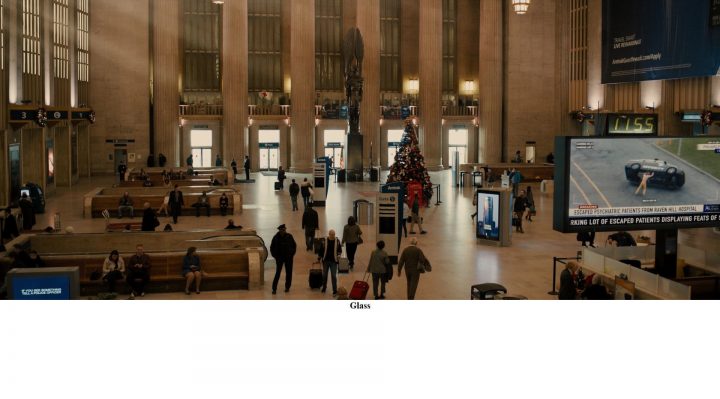

The children bid their mother farewell at the 30th Street Station, a place that figures prominently in the “Eastrail 177 trilogy” of Unbreakable, Split and Glass (but when David is trying out his new power in the first film, it seems to be another station) as well as The Happening, as seen in this slide show:

The Sixth Sense: Nana throwing up during the first night is as shocking and disgusting as the vomiting ghost. Also like in the earlier film, the father who has left the family has adversely affected the well-being of those left behind.

Unbreakable: The children’s fear of mirrors and germs is somewhat reminiscent of David Dunn’s weakness of water (as well as the Signs aliens), and the boy hero’s pathological fear in After Earth. When Becca uses the camera as a club to break the lock, the attention to detail and realism beyond the call of duty in a shot that basically appears as a blur to the viewer recalls the somersault David undergoes when the Orange Man pushes him off the veranda into the swimming pool. The slow zoom in a single-take scene during Becca’s interview harks back to the elaborate use of quiet, sneaky camera movement in Shyamalan’s early films, most of all in Unbreakable, as described here.

Signs: The tension between the children behind the closed door of their bedroom and mysterious, ominous events on the other side is reminiscent of the scene with the alien locked in behind the pantry door. The scraping against the door when Nana is sundowning and even more the sharp noise of a powerful knock when she is outside with a knife recalls the aliens on the other side of the cellar door trying to get in. All the handheld camera has a precursor in the footage of birthday party (shot by the director himself) which gives the world the first glimpse of an alien. Like in the earlier film, except for the scenes at home bookending the film, the action is confined to a farm, only broken by one trip to a town. The climax sees the children defeat a physical threat that also makes them overcome their failings – Becca her fear of mirrors, Tyler breaks out of his paralysis – like Graham gets his faith back (and the After Earth boy overcomes his fear).

The Village: Like Nana and Pop tell the kids they are their grandparents, in the earlier film older people are lying to the young, about the time period and the monsters in the woods. Like Nana and Pop Pop’s private mythology which they tell themselves to cope, the elders of the village have built up a fictional mythology. The shots of naked trees have some kinship to the trees in the forest during Ivy’s journey. Tyler’s interview with an open door in the background is reminiscent of the countless shots of doors, very often from inside buildings with a prominent open door. Nana’s rocking chair points back to the many chairs, very often of the same type. Like “the old shed that is not to be used” in the village, Pop Pop is doing mysterious business in a shed – but what a hilarious difference between his used diapers and the villagers’ monster paraphernalia…!

Lady in the Water: Nana’s story in her interview is in its childlike simplicity as well as connection to water and fantastical creatures reminiscent of the bedtime story in the earlier film. (The foreign planet in her story is a slight link to the aliens in Signs.) The childish names of Nana and Pop Pop, as well as the connections to Hansel and Gretel, are other connections to the nature of a bedtime story. That film was inspired by a bedtime story Shyamalan told to his small children, and The Visit too might be a case of familial inspiration.

The Happening: The ominous exterior shot of a tree swing before the board game scene refers back to the barricaded house and a similar swing outside it. In both cases, the swing is creaking ominously. In the third act the refugees arrive at an isolated house much like the farm in The Visit, where awful things will happen. Nana in her more outrageous moments is reminscent of the Crazy Lady, whom we meet in this article. The latter is slapping the hand of the eight-year-old Jess, and old people’s cruelty against children is enormously expanded in The Visit.

Split: Its abundance of point-of-view shots might be influenced by the ubiquity of subjective camera in its predecessor The Visit. Like Becca is struggling to overcome a locked door, Casey is hammering away at her cell door (and the whole plot revolves around the girls trying to escape their confinement in that room).

Glass: David Dunn too is hammering on his own cell door in this film. The children are using a camera as a surveillance instrument, and such cameras play a pivotal role at the psychiatric institution in the later film. And the way Nana is using the camera for her own purposes is an echo of how Elijah will turn them into his own advantage.

Old: the way Becca ends up highly decentred in her interview session points forward to the doctor in the later film sitting in shock after having killed another tourist:

Other films: Nana’s look and behaviour in some scenes bring our thoughts to the “hag horror” genre…

*

At the end of Tyler’s rap there is a break in the titles, so he can visually reign supreme with his punchline, which also seems a suitable place to end this meticulous investigation of The Visit.

*

Enclosure: Tiny inconsistencies

(These items come in addition to the minor problems described in the first article.) In two-camera scenes, normally the cameras are shown to already point in the right direction to be able to capture the next shot. This is about the only small inconsistency this author has been able to spot.

In both cases it feels odd that Becca would have changed the framing in the middle of the interview, especially in Nana’s case since there did not seem a natural break in the dialogue. In the last case, however, she might have got the idea of the slow zoom-in on Mom after the start and moved back to get room for it. There is a similar change of framing while Tyler is unpacking but he is such rebellious subject that it is only natural that the scene would consist of several takes.